A new way to control the light that exotic crystal semiconductors emit could lead to more efficient solar cells and other advances in electronics, according to new research.

The study involves crystals called hybrid perovskites, which consist of interlocking organic and inorganic materials, and they have shown great promise for use in solar cells.

The finding could lead to novel electronic displays, sensors, and other devices that light activates. It could also bring more efficiency at a lower cost to manufacturing of optoelectronics, which harness light.

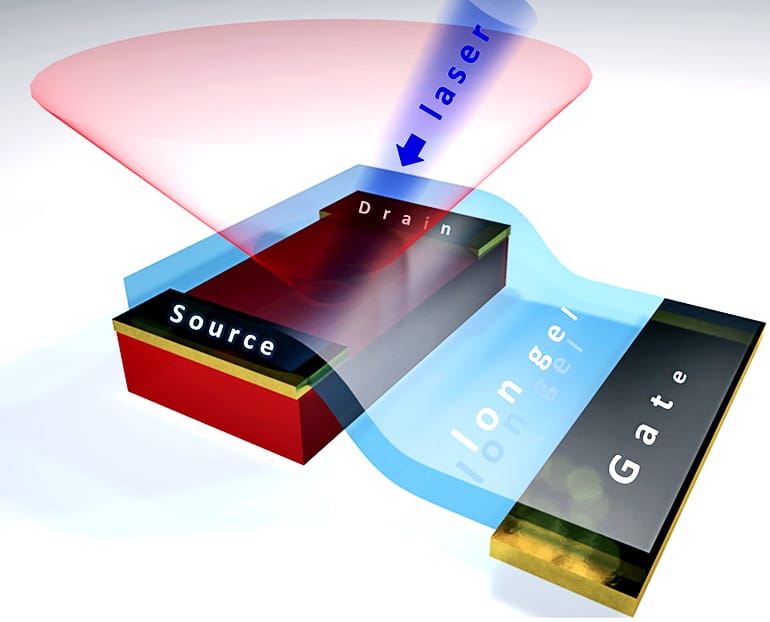

The research team found a new way to control light (known as photoluminescence) emitted when a laser excites perovskites. Researchers can increase the intensity of light a hybrid perovskite crystal emits by up to 100 times simply by adjusting voltage they apply to an electrode on the crystal surface.

“To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that the photoluminescence of a material has been reversibly controlled to such a wide degree with voltage,” says senior author Vitaly Podzorov, a professor in the physics and astronomy department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

“Previously, to change the intensity of photoluminescence, you had to change the temperature or apply enormous pressure to a crystal, which was cumbersome and costly. We can do it simply within a small electronic device at room temperature.”

Semiconductors like these perovskites have properties that lie between those of the metals that conduct electricity and non-conducting insulators. Scientists can tune their conductivity in a very wide range, making them indispensable for all modern electronics.

“All the wonderful modern electronic gadgets and technologies we enjoy today, be it a smartphone, a memory stick, powerful telecommunications and the internet, high-resolution cameras, or supercomputers, have become possible largely due to the decades of painstaking research in semiconductor physics,” Podzorov says.

Understanding photoluminescence is important for designing devices that control, generate or detect light, including solar cells, LED lights, and light sensors. The scientists discovered that defects in crystals reduce the emission of light and applying voltage restores the intensity of photoluminescence.

Hybrid perovskites are more efficient and much easier and cheaper to make than standard commercial silicon-based solar cells, and the study could help lead to their widespread use, Podzorov says.

An important next step would be to investigate different types of perovskite materials, which may lead to better and more efficient materials in which photoluminescence can be controlled in a wider range of intensities or with smaller voltage, he says.

The research appears in Materials Today. Additional researchers from Rutgers, the University of Minnesota, and the University of Texas at Dallas contributed to the work.

Source: Rutgers University