The more time you spend on social media, the more likely you are to want to undergo a cosmetic procedure, new research shows.

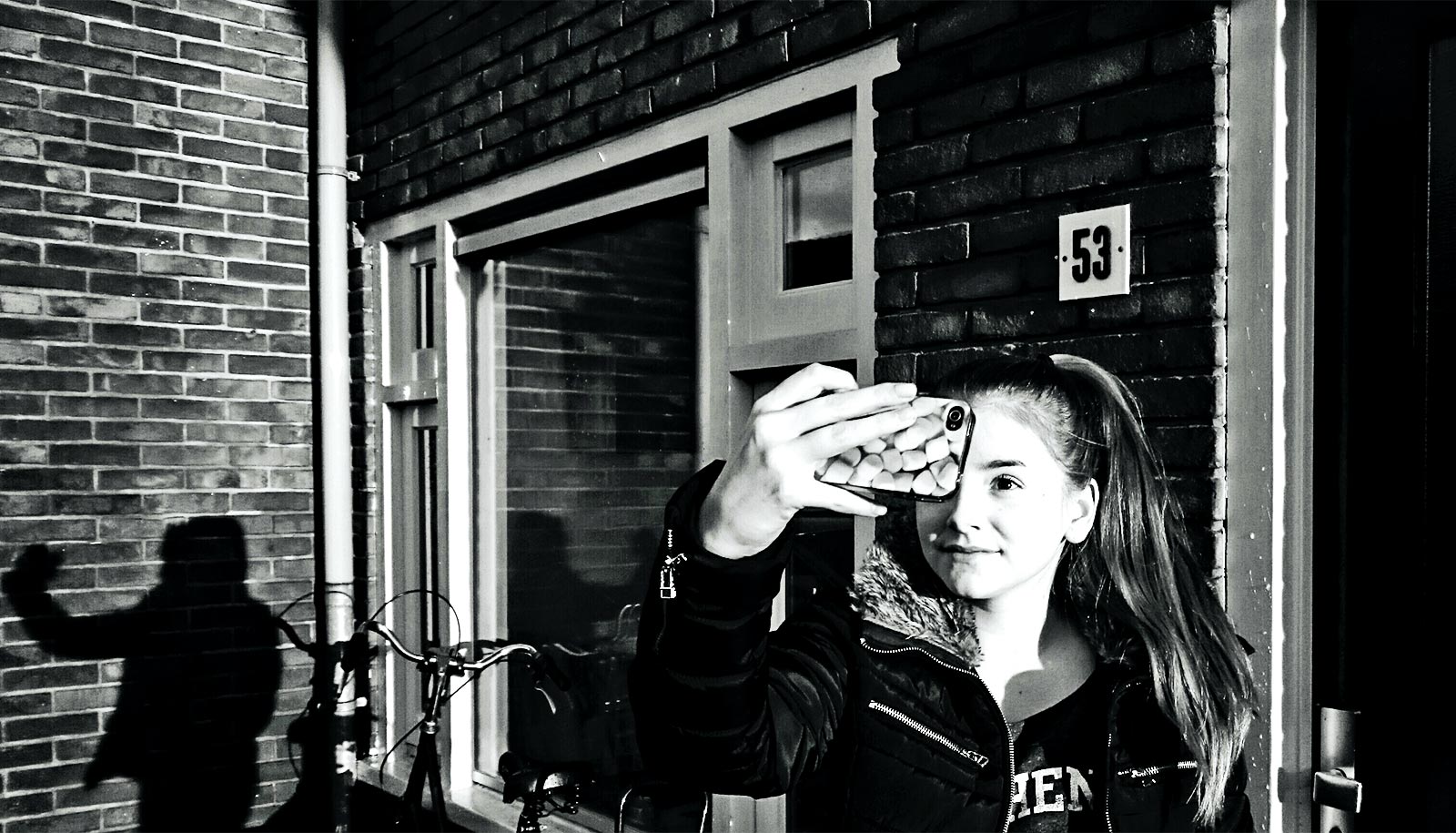

It’s a familiar pattern: you open your social media app of choice and end up sucked into a digital wormhole, mindlessly scrolling while the real world fades away. Maybe you even decide to post something, and pick out a filter to apply to your latest selfie or vacation photo. Or maybe you run your pic through an app like Facetune, tweaking your appearance to look your best.

Your photo then becomes one of the countless altered images coursing through social media users’ feeds, subtly shifting the goalposts for conventions of attractiveness. The question is: What effect does that have on our perceptions of ourselves and our willingness to make more permanent changes to our appearance?

The new study comes at a time when it’s easier than ever to go under the knife (or needle) to alter your appearance. Elective procedures—non-medically necessary dermal fillers, Botox, chemical peels, laser treatments, implants, plastic surgery—have become more accessible in recent years, in part due to developments in cosmetic technology.

And, with more and more celebrities being open about their look-changing procedures—like actress Megan Fox on Alex Cooper’s Call Her Daddy podcast—they’re also much less taboo.

The researchers set out to understand how social media influences users’ perceptions of beauty, and if popular apps inadvertently encourage people to alter their appearance. They polled 175 individuals at an outpatient dermatology clinic from 2019 to 2022 about their social media usage, their perception of cosmetic procedures, and their personal desire to undergo cosmetic procedures.

The study also split respondents into two groups—pre-pandemic and post-pandemic—to analyze whether a recent national rise in cosmetic dermatology was driven by COVID-era changes in social media and video conferencing use.

The findings appear in the Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology.

The results show that spending time on image-led platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—and, in particular, adding filters or using photo-editing apps before sharing photos—strongly correlated with respondents’ desire to undergo a cosmetic procedure. The researchers also found that following influencers and celebrities on social media made respondents significantly more likely to want to undergo cosmetic work, as did following accounts that highlight cosmetic procedures (such as those that analyze before and after pictures).

The study noted a major bump among respondents from the post-pandemic group who followed cosmetic procedure—related accounts online and indicated a desire to undergo work of their own.

“One of the most significant findings was that many more people post-COVID had thought about having a cosmetic procedure done, or had even discussed it with a dermatologist or a physician, and believed that doing so would help their self-esteem,” says Neelam Vashi, a Boston University medical school associate professor of dermatology and corresponding author of the study.

That doesn’t mean social media is directly responsible for patients going out and seeking treatment, Vashi says. But a user who was already considering pursuing a treatment—say, lip injections for fuller lips or buccal fat removal for more pronounced cheekbones—is more likely to book an appointment as a result of targeted exposure to procedures online.

The findings weren’t necessarily surprising to Vashi, founder of the BU Center for Ethnic Skin and director of the BU Cosmetic and Laser Center at Boston Medical Center, the University’s primary teaching hospital.

“Much of my research revolves around understanding the intricacies of beauty perception, and what defines beauty standards,” she says. “In the logic of social media, the use of filters has completely changed our perception of beauty and what can be achieved.”

And it’s not just social media driving the results. The rise of video conferencing during COVID lockdowns also likely contributed to patients’ increasing desire to get work done, the researchers conclude.

“Even on Zoom, there’s a feature where you can blur your appearance and remove any blemishes,” says Vashi, who notes an uptick in her patients asking for procedures to even their skin tones.

Self-esteem is at the core of the study, according to Vashi. In our increasingly visual world—and one in which everything we see online is potentially edited or AI-generated—it can be demoralizing when your appearance doesn’t match up with the “ideals” presented to you online.

Even when it’s your own face you’re comparing yourself to: in the study, the research team cites Vashi’s prior writings on “Snapchat dysmorphia,” which describes patients dissatisfied by not looking like the filtered versions of themselves they post online.

In the past, Vashi’s patients would sometimes bring in photographs of celebrities they wanted to emulate. “Now, when people are able to filter their own face and make it look more beautiful—even the skin tone, angulate the chin, raise the cheekbones, enlarge the eyes—they bring in these images of themselves that have become very realistic to them because it’s just a beautified version of their own face,” she says.

Of course, Vashi adds, there’s nothing wrong with wanting to improve your appearance—that’s why we do things like workout, wear makeup, buy new clothes, and myriad other improvement-focused activities. It only becomes concerning when patients seek out cosmetic changes as a fix-all Band-Aid for their self-esteem issues, or become fixated on unrealistic expectations for themselves, she says.

Going forward, Vashi hopes the study motivates dermatologists and other providers to further check in with patients about their social media usage and why they might be seeking treatments. She also hopes it inspires social media users to be mindful of how they use the internet, and to step away from their screen if they notice their self-esteem taking a hit.

Parents, too, should monitor what their children are consuming online, and should be prepared to have conversations about how that content can influence how they feel about themselves.

Zoom, social media—”they’re not going anywhere,” Vashi says. “In looking at ourselves and comparing it to what we see on screens, it’s really going to take an effort by all parties to keep a healthy outlook on what we see online.”

Source: Alene Bouranova for Boston University