A look at the dynamics of essential proteins that help DNA fold into its compact, functional form in chromosomes reveals that a key protein’s “coiled coils” braid around each other and writhe like snakes as they form bigger loops in the DNA.

The loops, in turn, bring together sites on DNA that regulate the transcription of genetic messages. While the loops and their functions are becoming better understood, until now nobody has been able to take a close look at the condensin and cohesin proteins that wrangle the DNA into shape.

The Rice University team led by physicists José Onuchic and Peter Wolynes and postdoctoral fellow Dana Krepel report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that structural maintenance of chromosomes (SMC) proteins may actively manage DNA through a novel mechanism.

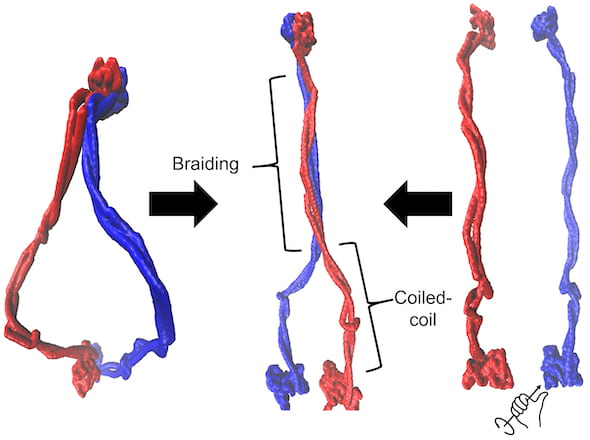

They found these proteins have ring-shaped lassos that consist of two 35-nanometer long protein coiled coils. These terminate on one end in a pair of “head unit” motors that bind to DNA coils, and on the other in “hinges” thought to open and close to entrap the strands.

The lab’s simulations showed these coiled coils are anything but limp lariats.

“We already knew the coiled coils have some sort of structural importance, but what we saw is that these long coils are quite active,” Krepel says. “We’re still investigating to what extent, but as we ran the simulations, we saw that the coils want to come together, kind of like headphones that get all twisted when you put them in your bag. We saw the twist right away.”

“Braiding is the word we use,” Wolynes adds. “People thought the coiled coils were simply hanging out, but they didn’t think they’d coil again on top of each other in an organized fashion.

“One of the key ideas of DNA physics is that DNA operates by changing its degree of coiling and its topology,” he says. “Well, braiding is a topological feature. We think we see that the topology of the protein can interact with the topology of the DNA much as threads entwine with each other on a spinning wheel.”

Krepel notes the SMC proteins are positively charged, and DNA is negatively charged. “We’re looking at how these positive and negative charges potentially play together,” she says.

“It seems clear the coils would almost certainly braid themselves around the DNA using these charge patterns,” says Wolynes, professor of chemistry, of biosciences, of physics, and astronomy and of materials science and nanoengineering.

Condensin and cohesin proteins in simulation

The project represents one of the largest challenges yet for the group’s modeling techniques, which in this case combined direct coupling analysis (DCA) of the co-evolution of related protein sequences and the atomic forces within the proteins that determine their form and function.

To complete the structure in which there were fewer evolutionary clues, the group used the AWSEM algorithm developed by Wolynes and colleagues to determine complete folded, functional structures from a coarse subset of atomic forces within a protein.

For this study, the team looked at condensin and cohesin structures with between 1,100 to 1,300 residues. “These are huge compared to proteins we have previously studied,” Wolynes says.

The size made it necessary to expand the tool set, says Onuchic, professor of physics and astronomy, of chemistry, and of biosciences. “An initial paper developed these tools but just for condensin in bacteria,” he says. “Utilizing the same approach of DCA combined with structure-based simulations, we are now investigating condensin and cohesin as they appear in humans.

“Using this method, we are able to predict the structures, but to understand the details of their dynamics requires real force fields,” Onuchic says. “So, starting from the initially predicted structures, we ran AWSEM simulations. These simulations revealed the braiding.”

Lassos and twists

The models further suggested that the ATPase motors that bind DNA can twirl the braids.

“We’re still guessing at the details, but we think when the two motors are both twisting to extrude DNA into loops, one untwisting and the other uptwisting, the lassos could transfer twisting of the coils into twisting around the DNA,” Wolynes says. “The coils aren’t just passively hanging there. They’re much more involved in the process than we thought.”

The next step, he says, will be to test an even larger system with two strands of DNA, a more realistic representation, to see if the twisting action holds true. That effort will be part of a larger one at CTBP to extend its theories on protein folding to the much bigger problem of chromosome dynamics. The researchers pointed out this will be one of the main goals of the center’s future work.

“This molecule and how it forms loops in DNA is a big part of many projects we have going on in chromosomes,” Wolynes says. “There are quite a few diseases that arise from chromosome disorganization, and we want to have a better understanding of the mechanism of how chromosomes form.”

The National Science Foundation, the Welch Foundation, and the Council for Higher Education of Israel supported the research.

Source: Rice University