With a few tweaks, smartwatches can detect a surprising number of things your hands are doing.

Researchers have used a standard smartwatch to figure out when a wearer was typing on a keyboard, washing dishes, petting a dog, pouring from a pitcher, or cutting with scissors.

By making a few changes to the watch’s operating system, the researchers could use its accelerometer to recognize hand motions and, in some cases, bioacoustic sounds associated with 25 different hand activities at around 95 percent accuracy. And those 25 activities are just the beginning of what might be possible to detect.

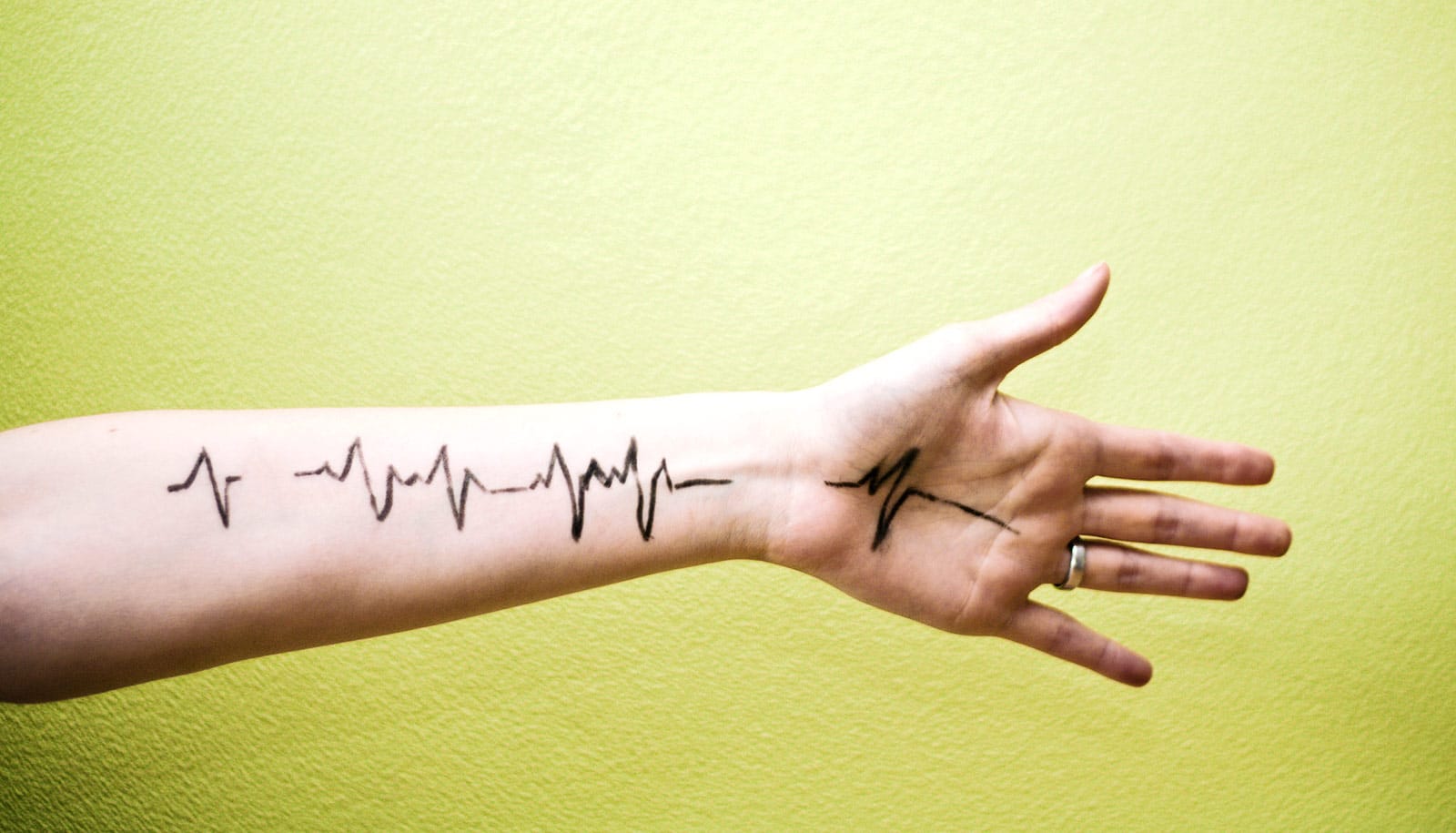

Sensing hand activity lends itself to health-related apps—monitoring activities such as brushing teeth, washing hands, or smoking cigarettes.

“We envision smartwatches as a unique beachhead on the body for capturing rich, everyday activities,” says Chris Harrison, assistant professor in the Human-Computer Interaction Institute at Carnegie Mellon University and director of the Future Interfaces Group.

“A wide variety of apps could be made smarter and more context-sensitive if our devices knew the activity of our bodies and hands.”

Just as smartphones now can block text messages while a user is driving, future devices that sense hand activity might learn not to interrupt someone while they are doing certain work with their hands, such as chopping vegetables or operating power equipment, says PhD student Gierad Laput. Sensing hand activity also lends itself to health-related apps—monitoring activities such as brushing teeth, washing hands, or smoking a cigarette.

Apps that provide feedback to users who are learning a new skill, such as playing a musical instrument or undergoing physical rehabilitation, may also be able to use hand-sensing. Apps might alert users to typing habits that could lead to repetitive strain injury, or assess the onset of motor impairments accompanying diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

Laput and Harrison began their exploration of hand activity detection by recruiting 50 people to wear specially programmed smartwatches for almost 1,000 hours while going about their daily activities. Periodically, the watches would record hand motion, hand orientation, and bioacoustic information, and then prompt the wearer to describe the hand activity—shaving, clapping, scratching, putting on lipstick, etc. Researchers labeled more than 80 hand activities in this way, providing a unique dataset.

For now, users must wear the smartwatch on their active arm, rather than the passive (nondominant) arm where people typically wear wristwatches, for the system to work. Researchers will explore what events the watches can detect using the passive arm in future experiments.

“The 25 hand activities we evaluated are a small fraction of the ways we engage our arms and hands in the real world,” Laput says. Future work likely will focus on classes of activities—those associated with specific activities such as smoking cessation, elder care, or typing and RSI.

Harrison and Laput will present their findings on this new sensing capability at CHI 2019, the Association for Computing Machinery’s Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems in Glasgow, Scotland.

The Packard Foundation, Sloan Foundation, and the Google PhD Fellowship supported this research.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University