Historical records could help us move toward more constructively addressing slavery’s legacy in the United States, says journalist Rachel L. Swarns.

“Growing up in Staten Island, New York, I lived just a few blocks away from a convent that ran a bookstore and a community festival that was a highlight of my childhood summers,” recalls Swarns, professor of journalism at New York University and a contributing writer for the New York Times.

“My mother, my aunts, three of my uncles, and both of my sisters were all educated by Catholic nuns. My mother and her family, who emigrated from the Bahamas to New York, even lived for a while on a farm run by Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker movement and a candidate for sainthood.”

Yet until four years ago, “when I started reporting on the Jesuit priests who sold 272 people to help keep Georgetown afloat,” Swarns says, “I knew nothing about the priests and nuns who bought and sold human beings.”

Swarns, who is black and Catholic and who goes to Mass with her family on Sundays, researched and wrote a series of stories in 2016 about Georgetown University, the Jesuit priests who founded and ran the college, and their ties to slavery. Since then, she has continued her research, reporting last year on the Catholic nuns who bought and sold enslaved people and the efforts that convents and other religious institutions are making now to atone for their participation in the American slave trade.

“People ask me whether this work has affected my faith. At first, it was astounding to me,” she says. “I soon realized that I shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, the Catholic Church, like so many American institutions, was deeply rooted in what was essentially a slave society.”

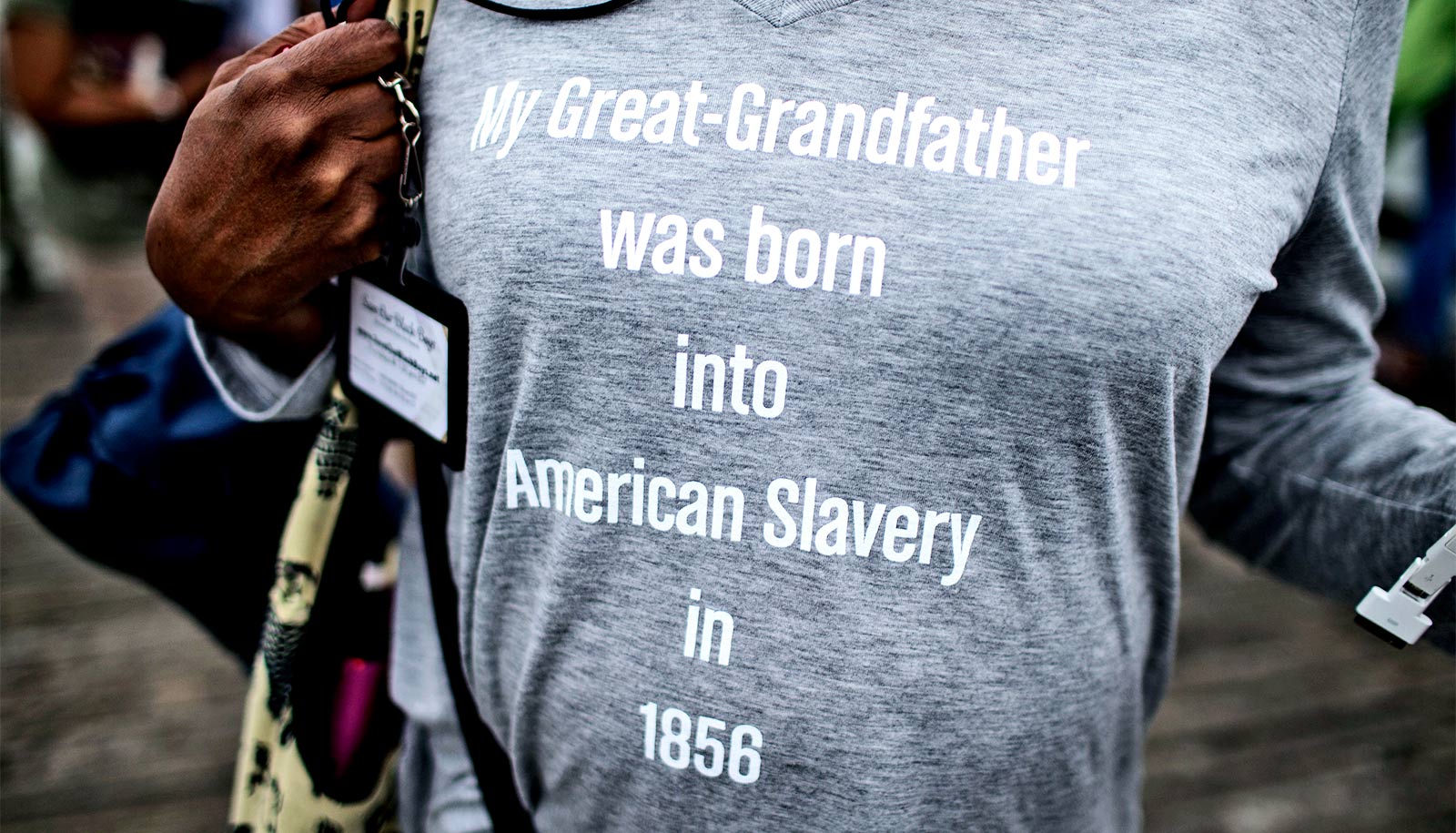

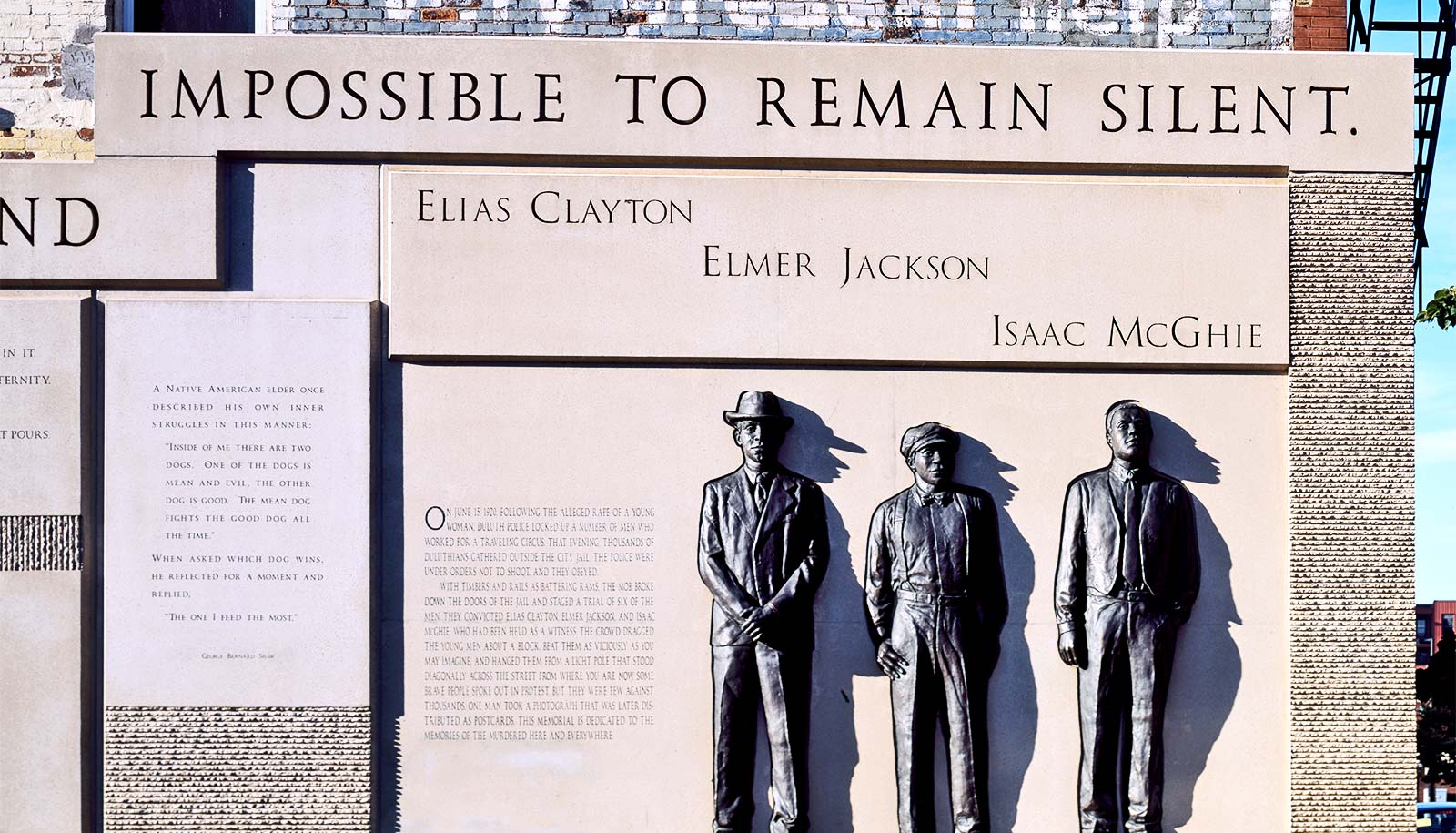

Her investigations were a part of a recent wave of public examination of the permanent and deep scar slavery has left on the nation—one that has led to renewed debate over whether and how institutions with historical ties to the slave economy can make amends today.

The topic took on newfound visibility in 2014, when author Ta-Nehisi Coates, now a distinguished writer in residence at the Carter Journalism Institute, authored “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic, helping to resurface consideration of compensating descendants of enslaved peoples. Five years later, Coates testified before the House Judiciary on behalf of HR 40, a bill that established a commission to study and develop reparation proposals. In 2016, Washington, DC saw the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which explores, in painful detail, the institution of slavery and its aftermath.

Today, there is widespread recognition of slavery’s impact in the 21st century. Last year, the Pew Research Center reported that more than 60% of Americans believe that slavery “affects the position of black people in American society today.” However, divisions on racial progress remain, with nearly 80% of black adults believing the US hasn’t made enough progress in giving black people “equal rights”—compared to under 4o% of white adults who feel this way.

The New York Times‘ 1619 Project—a series of essays examining the myriad ways that slavery was and continues to be woven into the American experience—has spawned a podcast, a high school curriculum, and an upcoming book.

Prior to joining the faculty at NYU, Swarns spent 22 years as a full-time reporter for the New York Times, where she served as a senior writer and a Washington correspondent, and became the first African American to serve as bureau chief in South Africa. She later penned American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama (Harper Collins, 2013), which traces the former first lady’s forebears back to the 1800s, identifying, for the first time, the white ancestors in Mrs. Obama’s family tree through archival research and DNA testing.

She is also a coauthor of Unseen: Unpublished Black History from the New York Times Photo Archives (Blackdog and Levanthal, 2017), which unearthed hundreds of powerful photographs that had languished unseen and unpublished for decades.

Here, Swarns explains how using the abundance of historical records can help us move toward more constructively addressing slavery’s tangled web of injustices:

How did your revelations on the Catholic priests and nuns and their ties to slavery effect greater perceptions of the church’s place in American history?

It astonishes us because we don’t realize how deeply slavery was embedded in our economy. Slavery fueled the growth of many of our contemporary institutions, including the Catholic Church. Many of us view the Catholic Church as a Northern church. But the Catholic Church established its foothold in the South and relied on plantations and slave labor to help finance the livelihoods of its priests and nuns, and to support its schools and religious projects.

This is history that we all should know. But we don’t. Enslaved people have largely been left out of the origin story that is traditionally told about the Catholic Church and other religious institutions. That’s changing, though. Religious institutions, including convents, seminaries, and others, are now taking the lead in the fledgling reparations movement that is emerging in this country. It is really something to see.

You’ve reported that many US corporations, including several that exist today, played a fundamental role in slavery. Do these businesses have an obligation to make amends for their companies’ past?

As a journalist, I’m not in the business of telling executives how their companies should grapple with their ties to slavery. I don’t see that as my role. But I do think that it’s critical for Americans to understand that universities and churches weren’t the only institutions to benefit from slavery. Banks, railroads, insurance companies, and the like did, too. It’s important for companies to acknowledge that.

We often think about slavery as old history, as history that’s completely disconnected from us. And that’s simply not the case. Some of those companies still have records that document their ties to slavery. I would urge them to make those records publicly available so that journalists and scholars can continue to document how slavery’s legacy lives in the contemporary institutions around us.

Why are many Americans still so unfamiliar with the foundational role that slavery played in this country?

I think about that a lot these days. Why don’t we know this history? The records documenting the ties to slavery are there: in our archives, in our historical societies, in our courthouses. Many historians have already unearthed these records and have told these stories.

There are probably a lot of reasons. But one reason, I think, is that we, as Americans, often prefer to avert our eyes. This history runs counter to the narrative that we like to tell about ourselves and to our ideals of equality and justice for all. Coming to an understanding that slavery was foundational for a country that expounds these ideals is profoundly difficult. So we rarely talk about it.

We rarely include it in the history pages of our corporate and church websites. We don’t teach our children enough about it in schools. We often embrace a comfortable, fictionalized view of history that says that only the slaveholders in the South benefited from slavery. And they are long gone. I think that’s easier for many of us to hold on to.

You were based in South Africa at the turn of the 21st century—a period that saw the country undergo the challenges of racial reconciliation. Are there any lessons for the United States?

I spent nearly four years in South Africa, which had only recently emerged from apartheid. The wounds inflicted by generations of white rule were still very, very fresh. I arrived after the Truth and Reconciliation process, which attempted to bring perpetrators and victims together. It was not a perfect process, but it was a concerted effort at reckoning with the past and compensating victims.

We’ve never tried to do that here, to come together as a country to reckon with slavery and its aftermath. I’m not sure what a formal process of healing would look like here, but I think we have to start by acknowledging the history and how it reverberates in the lives of so many of us still.

How did it feel to discover that, within just the past few months, a number of institutions have announced plans to create reparations funds to atone for their ties to slavery?

In October of 2019, Georgetown University announced that it would establish a fund to benefit the descendants of those enslaved people. It is the first major American university to take a stab at reparations.

There’s a real reckoning happening right now. Virginia Theological Seminary and Princeton Theological Seminary have also created reparations funds, and other religious institutions are following suit. People will debate whether this is good or bad or adequate. But the reckoning is real. I hope that my work has contributed to this growing understanding of the foundational role that slavery and enslaved people played in the development of our country and I hope it will continue to contribute to that.

Source: NYU