Using satellite imaging and drone reconnaissance, archaeologists have discovered an ancient irrigation system that once allowed a farming community in arid northwestern China—one of the world’s driest desert climates—to raise livestock and cultivate crops.

Lost for centuries in the barren foothills of China’s Tian Shan Mountains, the ancient farming community is hidden in plain sight—appearing to be little more than an odd scattering of round boulders and sandy ruts when viewed from the ground.

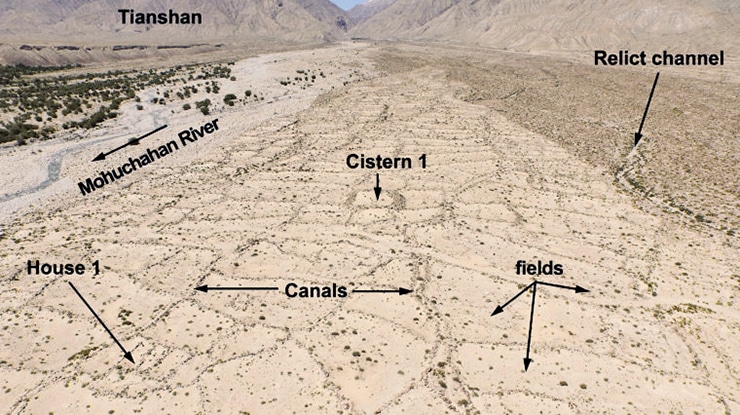

Surveyed from 30 meters above using drones and specialized image analysis software, however, the site shows the unmistakable outlines of check dams, irrigation canals, and cisterns feeding a patchwork of small farm fields.

Initial test excavations also confirm the locations of scattered farmhouses and grave sites, says Yuqi Li, a doctoral student in the anthropology department at Washington University in St. Louis.

Changing ideas about nomads

Preliminary analysis, as detailed by Li and coauthors in Archaeological Research in Asia, suggests that the irrigation system was built in the 3rd or 4th century CE by local herding communities looking to add more crop cultivation to their mix of food and livestock production.

“As research on ancient crop exchanges along the Silk Road matures, archaeologists should investigate not only the crops themselves, but also the suite of technologies, such as irrigation, that would have enabled ‘agropastoralists’ to diversify their economies,” Li says.

“In recent years, more and more archaeologists started to realize that most of the so-called pastoralist/nomad communities in ancient Central Asia were also involved in agriculture,” Li adds. “We think it’s more accurate to call them agropastoralists, because having an agricultural component in their economy was a normal phenomenon instead of a transitional condition.”

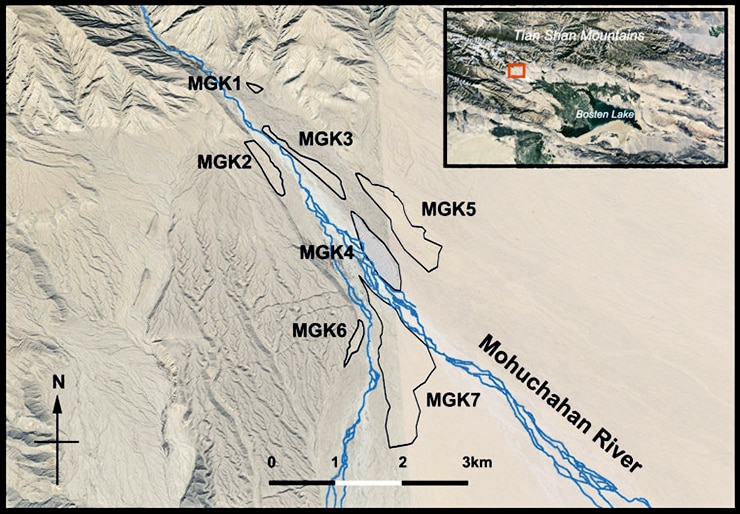

Li and his colleagues first used satellite imagery to target an area known as MGK, so named for the adjacent Mohuchahan Valley, an intermontane valley of the Tian Shan.

The researchers created more detailed on-site mapping using a consumer-grade quadcopter drone and new photogrammetry software that stitched together about 2,000 geotagged aerial photos to create 3D models of the site.

The site offers a remarkably well-preserved example of a small-scale irrigation system that early farmers devised to grow grain crops in a climate that historically receives less than 3 inches (66 millimeters ) of annual rainfall—about one-fifth of the water deemed necessary to cultivate even the most drought-tolerant strains of millet.

Researchers believe the site was used to cultivate millet, barley, wheat, and perhaps grapes.

Han dynasty

The discovery is important, Li says, because it helps to resolve a long-running debate over how irrigation technologies first made their way into this arid corner of China’s Xinjiang region.

While some scholars suggest that the troops of China’s Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) first brought all major irrigation techniques to the region, the new study suggests that local agropastoral communities adopted many arid-climate irrigation techniques before the Han dynasty and kept using them to the post-Han era.

A stream known as the Mohuchahan River drains the valley and carries a seasonal trickle of snow-melt and scarce rainfall down from the mountains before vanishing in the sands of China’s vast Taklamakan Desert.

The Tian Shan Mountains, which form the northern border of this desert, are part of a chain of mountain ranges that have long served as a central corridor for the prehistoric Silk Road routes between China and the Near East.

Li’s research on MGK builds on earlier work by colleague Michael Frachetti, a professor of anthropology, whose research suggests that herding communities living along these mountain ranges formed a massive exchange network that spanned much of the Eurasian continent.

Ongoing research by Frachetti and his colleagues contends that the seeds of early domestic crops gradually spread to new areas along this Inner Asian Mountain Corridor through social networks formed by ancient nomadic groups—who met as they moved herds to seasonal pastures.

Based on his research at MGK, Li argues that early irrigation technologies also followed this same route, passing from one pastoral group to another over thousands of years.

Li notes that small-scale irrigation systems similar to MGK were established at the Geokysur river delta oasis in southeast Turkmenistan about 3,000 BCE and further west at the Tepe Gaz Tavila settlement in Iran about 5,000 BCE.

The Wadi Faynan farming community, established in a desert environment in southern Jordan during the late Bronze Age, has an irrigation system nearly identical to the one at MGK, including boulder-constructed canals, cisterns, and field boundaries.

Compared with known Han Dynasty irrigation systems in the Xinjiang region, the MGK system is small, irrigating about 500 acres across seven parcels along the Mohuchahan River. The current study focuses on one of these seven parcels, known as MGK4, which provided irrigation for about 60 acres.

Did nomads and their herds carve out the Silk Road?

By contrast, the “tuntian” irrigation systems—introduced by the Han Dynasty at the Xinjiang communities of Milan and Loulan—used longer, wider, and deeper straight-line channels to irrigate much larger areas, with one irrigating more than 12,000 acres.

Irrigation know-how

While some researchers estimate that Han Dynasty workers would have had to move about 1.5 million cubic meters of dirt to build a tuntian system capable of irrigating 2,500 acres, Li calculates that a small community of farmers could have constructed the 500-acre system at MGK with much less effort in a few years.

“The irrigation system at MGK4 suggests that, although the Han Dynasty brought sophisticated irrigation technology to Xinjiang, this set of technology did not replace the irrigation technology that appeared earlier in Xinjiang,” Li says. “Instead, it continued to be used in the post-Han period. We believe the reason was that this set of technology was well-adapted to the ecological and social conditions faced by local agropastoralist communities.

“Given recent research on the routes of early crop exchanges, it is possible that the technological ‘know-how’ of irrigation in this region originated with earlier agropastoral traditions in western Central Asia,” he says.

“As a fundamental technology that underpinned the agropastoralist societies in Xinjiang, irrigation probably spread to Xinjiang through the Inner Asian Mountain Corridor along with crops during prehistory.”

DNA suggests Yiddish began on the Silk Road

A grant from the National Geographic Society supported Li’s work.

Additional coauthors of the study are from the Earth Observatory of Singapore; Nanyang Technological University, Singapore; the Hejing County Office for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments in Xinjiang, China; and the Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.