Ash from an enormous flare-up of volcanic eruptions toward the end of the dinosaurs’ reign kicked off a chain of events that led to the formation of shale gas and oil fields from Texas to Montana, a new study suggests.

“One of the things about these shale deposits is they occur in certain periods in Earth’s history, and one of those is the Cretaceous time, which is around the time of the dinosaurs,” says lead author Cin-Ty Lee, professor and chair of Rice University’s Earth, environmental, and planetary sciences department.

“This was about 90 million to 100 million years ago, which is about the same time as a massive flare-up of arc volcanoes along what is today the Pacific rim of the Western United States,” he explains.

Ash from the past

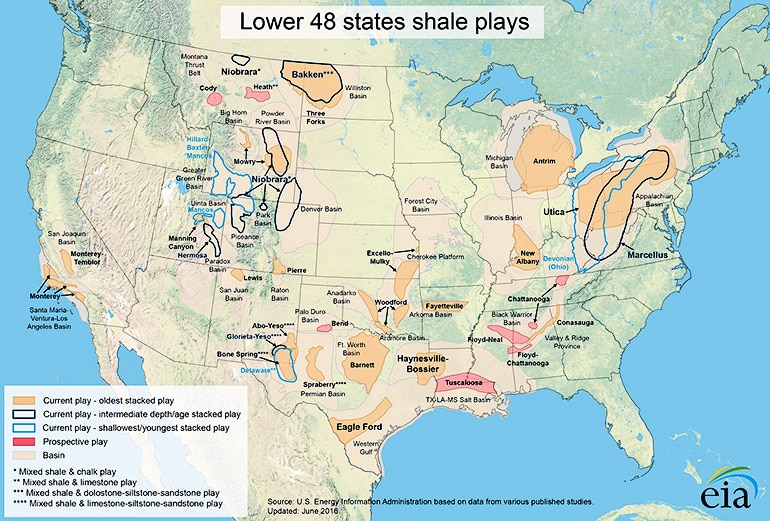

Advances in horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing over the past 20 years led to a US energy boom in “unconventionals,” a category that includes the shale gas and “tight” oil found in shale fields like the Cretaceous Eagle Ford and Mowry and older ones like the Barnett and Bakken.

“These types of natural gas and oil are in tiny, tiny pores that range from a few millionths of a meter in diameter to a few thousandths of a meter,” Lee says. “The deposits are in narrow bands that can only be accessed with horizontal drilling, and the oil and gas are locked in these little pockets and are only available with techniques like hydraulic fracturing.”

Lee says that there have always been hints of a connection between ancient volcanic eruptions and unconventional shale hydrocarbons. During field trips out to West Texas, he and Rice students noticed hundreds of ash layers in exposed rock that dated to the Cretaceous period when much of western North America lay beneath a shallow ocean.

One of these trips happened in 2014 while Lee and colleagues were also studying how a flare-up of Cretaceous-era arc volcanoes along the US Pacific rim had impacted Earth’s climate through enhanced volcanic production of carbon dioxide.

“We had seen ash layers before, but at this site we could see there were a lot of them, and that got us thinking,” Lee says. He and colleagues decided to investigate the ash beds in collaboration with Daniel Minisini, a colleague at Shell Oil who had been doing extensive work on quantifying the exact number of ash beds.

“It’s almost continuous,” Lee says. “There’s an ash layer at least every 10,000 years.”

The team determined that ash had come from hundreds of eruptions that spanned some 10 million years. The layers had been transported several hundred miles east of their volcanic source in California where ash was deposited on the seafloor after being blown through plumes that rose miles into the atmosphere and drifted over the ocean. Lee and students analyzed samples of the ash beds in the geochemical facilities at Rice.

“Their chemical composition didn’t look anything like it would have when they left the volcano,” he says. “Most of the original phosphorus, iron, and silica were missing.”

‘Dead zones’

That brought to mind the oceanic “dead zones” that often form today near the mouths of rivers. Overfertilization of farms pumps large volumes of phosphorus down these rivers. When that hits the ocean, phytoplankton gobble up the nutrients and multiply so quickly they draw all the available oxygen from the water, leaving a “dead” region void of fish and other organisms.

Lee suspected the Cretaceous ash plumes might have caused a similar effect. To nail down whether the ash could have supplied enough nutrients, researchers used trace elements like zirconium and titanium to match ash layers to their volcanic sources. By comparing rock samples from those sources with the depleted ash, the team was able to calculate how much phosphorus, iron, and silica were missing.

“Normally, you don’t get any deposition of organic matter at the bottom of the water column because other living things will eat it before it sinks to the bottom,” Lee says. “We found the amount of phosphorus entering the ocean from this volcanic ash was about 10 times more than all the phosphorus entering all the world’s oceans today. That would have been enough to feed an oxygen-depleted dead zone where carbon could be exported all the way down to the sediment.”

The combination of the ashfall and oceanic dead zone concentrated enough carbon to form hydrocarbons.

Shale gas beats coal in lifetime pollution head-to-head

“To generate a hydrocarbon deposit of economic value, you have to concentrate it,” Lee says. “In this case, it got concentrated because the ashes drove that biological productivity, and that’s where the organic carbon got funneled in.”

Looking elsewhere

Lee says shale gas and tight oil deposits are not found in the ash layers but appear to be associated with them. Because the layers are so thin, they don’t show up on seismic scans that energy companies use to look for unconventionals. The discovery that hundreds of closely spaced ash layers could be a tell-tale sign of unconventionals might allow industry geologists to look for bulk properties of ash layers that would show up on scans, Lee says.

“There also are implications for the nature of marine environments,” he says. “Today, phosphorus is also a limiting nutrient for the oceans, but the input of the phosphorus and iron into the ocean from these volcanoes has major paleoenvironmental and ecological consequences.”

No, volcanoes didn’t kill off the dinosaurs

While the study looked specifically at the Cretaceous and North America, Lee says arc volcano flare-ups at other times and locations on Earth may also be responsible for other hydrocarbon-rich shale deposits.

“I suspect they could,” he says. “The Vaca Muerta field in Argentina is the same age and was behind the same arc as what we were studying. The rock record gets more incomplete as you go further back in time, but in terms of other US shales, the Marcellus in Pennsylvania was laid down more than 400 million years ago in the Ordovician, and it’s also associated with ashes.”

The researchers report their findings in the journal Scientific Reports.

The funding for the research came from the National Science Foundation, the Guggenheim Foundation, and the Geological Society of America.

Source: Rice University