New research sheds light on “sextortion,” a lesser-known internet crime that poses a threat to adults and minors, and the importance of protecting the public from online criminals.

“Sextortion is the use of intimate images or videos that have been captured to then extort compliance from a victim,” says coauthor Roberta Liggett O’Malley, a doctoral student in criminal justice at Michigan State University.

“What makes it different from any other crime is the threat to release. A perpetrator could say, ‘I have these images of you and will publish them unless you…’ to get more images or even in exchange for money.”

In many cases of sextortion, perpetrators don’t actually possess the images or videos they’re using as leverage. Instead, offenders manipulate victim behavior by tapping into the fear of not knowing whether the threat is real.

The research suggests the current focus on dissemination of images online may overshadow the issue of threat-based harassment online, like sextortion. While most US states have laws against revenge porn, the study makes a case for increasing awareness and changing legislation to include other forms of internet-based sexual abuse crimes.

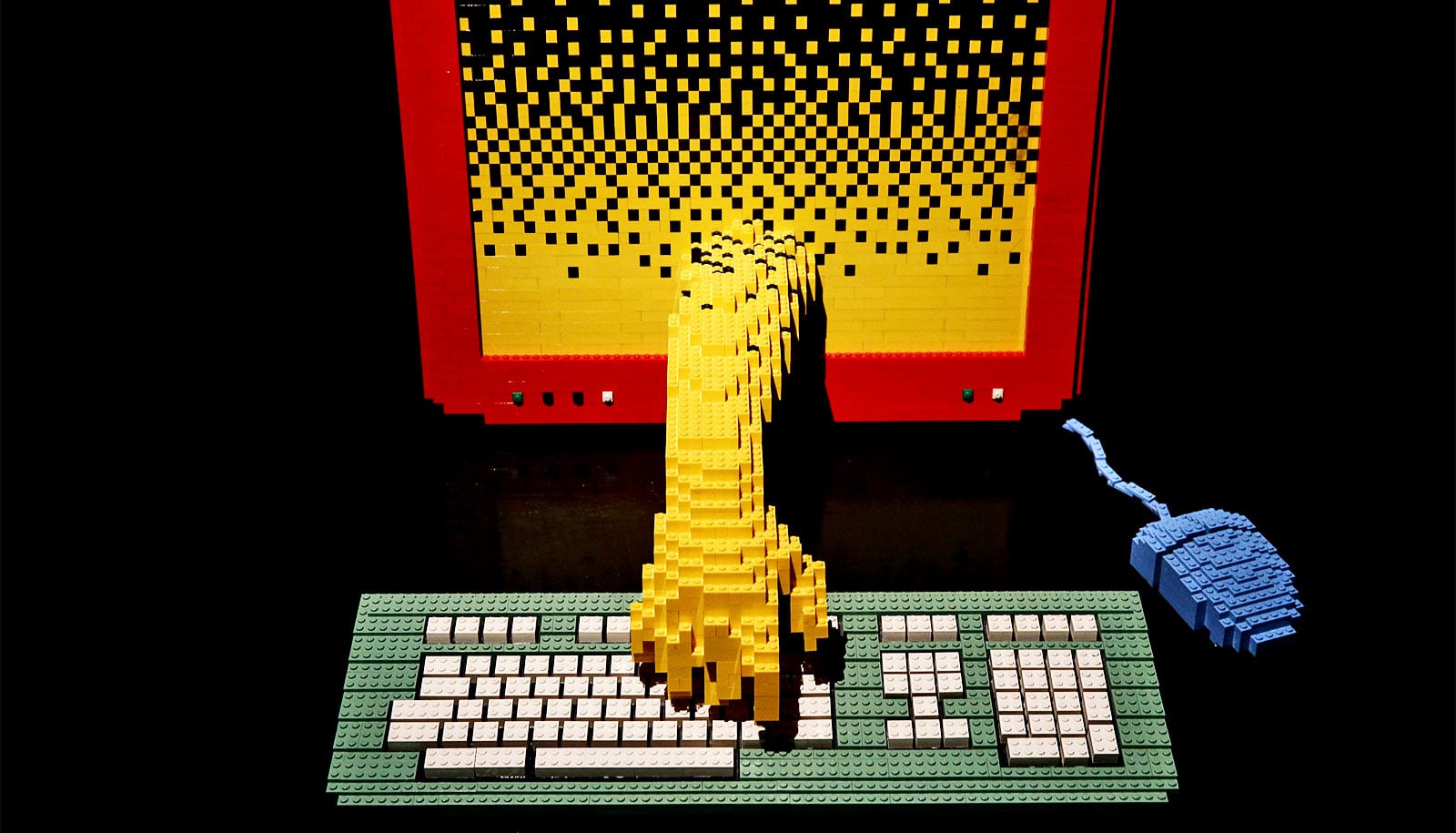

“Much of the fear comes from the belief that hackers can do anything involving technology, from the ability to see someone’s web browser history to hacking into a webcam or Nest device,” says coauthor Karen Holt, an assistant professor of criminal justice. “That’s why sextortion is so effective—it creates a huge amount of uncertainty and fear that victims end up complying versus saying, ‘I think you’re bluffing, and if I ignore you, then I’m fine.'”

Liggett O’Malley and Holt says men are less likely to report these crimes to police out of embarrassment or shame, but also don’t experience the longevity of harassment experienced by minors.

“The victims are overwhelmingly minors and females, but if the objective is to get money, they’re almost always targeting men,” Liggett O’Malley says. “These two groups of people experience a similar crime in very different ways.”

Analysis of 152 cyber sextortion offenders uncovered four distinct types: minor-focused, targeting victims under 18 years of age; cybercrime, targeting victims using computer-based tactics like hacking; intimately violent, targeting former or current romantic partners; and transnational, targeting strangers strictly for financial reasons.

Holt explains that the four themes reflect different motivations for what offenders want from their victims. A survey of 1,631 cyber sextortion victims found 46% were minors, making crimes against minors a focus for law enforcement and in research literature.

“The disproportionate focus on minor victims has led to new laws that protect minors from adult sexual solicitation online, but there are few legal protections for adult male and female victims,” Liggett O’Malley says.

Researchers are starting to see a lot of other perpetrators use sextortion. Within a domestic violence context, partners may share images consensually, only to have those images later used as leverage in the relationship. In other instances, transnational organizations employ scams in which individuals pretend to be a man or women on the internet, engaging in webcam sessions with victims and immediately threatening to release a recording unless money is provided.

Awareness and reporting of sextortion crimes, while acting responsibly online, are key in protecting adults and children.

“As digital citizens, we have to start advocating for more accountability on behalf of platforms to take these images down, or to report harassment,” Holt says. “A lot of offline crimes have an online component, and oftentimes law enforcement and our behavior don’t catch up. We need to think about our own personal safety, both offline and online.”

Researchers like Liggett O’Malley and Holt also advocate for federal laws to address the legal loopholes of sextortion.

“We can’t only be focused on revenge porn,” Liggett O’Malley says. “We need to stop and think about all the ways in which images are used against people and to think about the way we construct these laws to ensure there are pathways for prosecution and arrest.”

The research appears in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

Source: Michigan State University