A new device improves on the sensitivity and versatility of sensors that detect doping in athletics, bomb-making chemicals, or traces of drugs. It could also cut costs.

To conduct these kinds of searches, scientists often shine light on the materials they’re analyzing. This approach is known as spectroscopy, and it involves studying how light interacts with trace amounts of matter.

One of the more effective types of spectroscopy is infrared absorption spectroscopy, which scientists use to sleuth out performance-enhancing drugs in blood samples and tiny particles of explosives in the air.

While infrared absorption spectroscopy has improved greatly in the last 100 years, researchers are still working to improve the technology.

“This new optical device has the potential to improve our abilities to detect all sorts of biological and chemical samples,” says Qiaoqiang Gan, associate professor of electrical engineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at University at Buffalo. Gan is lead author of the study in Advanced Optical Materials.

The sensor works with light in the mid-infrared band of the electromagnetic spectrum. This part of the spectrum is used for most remote controls, night-vision, and other applications.

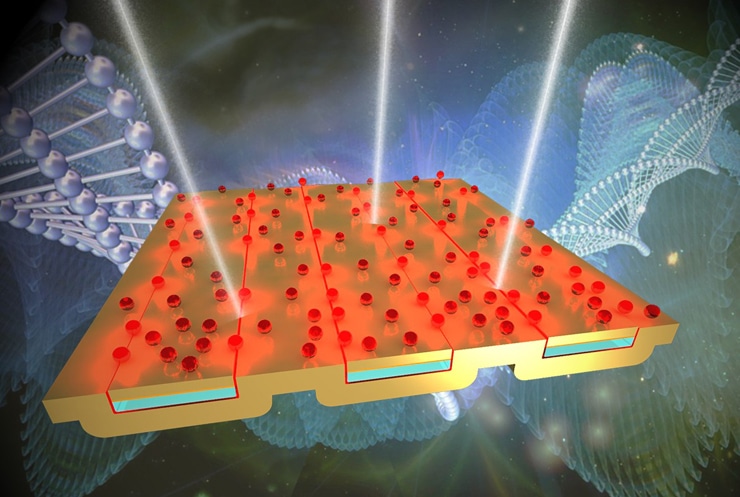

The sensor consists of two layers of metal with an insulator sandwiched in between. Using a fabrication technique called atomic layer deposition, researchers created a device with gaps less than five nanometers (a human hair is roughly 75,000 nanometers in diameter) between two metal layers. Importantly, these gaps enable the sensor to absorb up to 81 percent of infrared light, a significant improvement from the 3 percent that similar devices absorb.

Laser device zaps air to detect harmful gas

The process is known as surface-enhanced infrared absorption (SEIRA) spectroscopy. The sensor, which acts as a substrate for the materials being examined, boosts the sensitivity of SEIRA devices to detect molecules at 100 to 1,000 times greater resolution than previously reported results.

The increase makes SEIRA spectroscopy comparable to another type of spectroscopic analysis, surface-enhanced Rama spectroscopy (SERS), which measures light scattering as opposed to absorption.

The SEIRA advancement could be useful in any scenario that calls for finding traces of molecules, says Ji, first author of the study and a PhD candidate in Gan’s lab. This includes but is not limited to drug detection in blood, bomb-making materials, fraudulent art, and tracking diseases.

Researchers plan to continue the research, and examine how to combine the SEIRA advancement with cutting-edge SERS.

Support for the research came from the National Science Foundation’s Nanomanufacturing program, the National Science Foundation of China, and the Chinese Scholarship Council.

Source: University at Buffalo