The seals of Iliamna Lake in Alaska are a robust yet highly unusual and cryptic posse. New research investigates their origins.

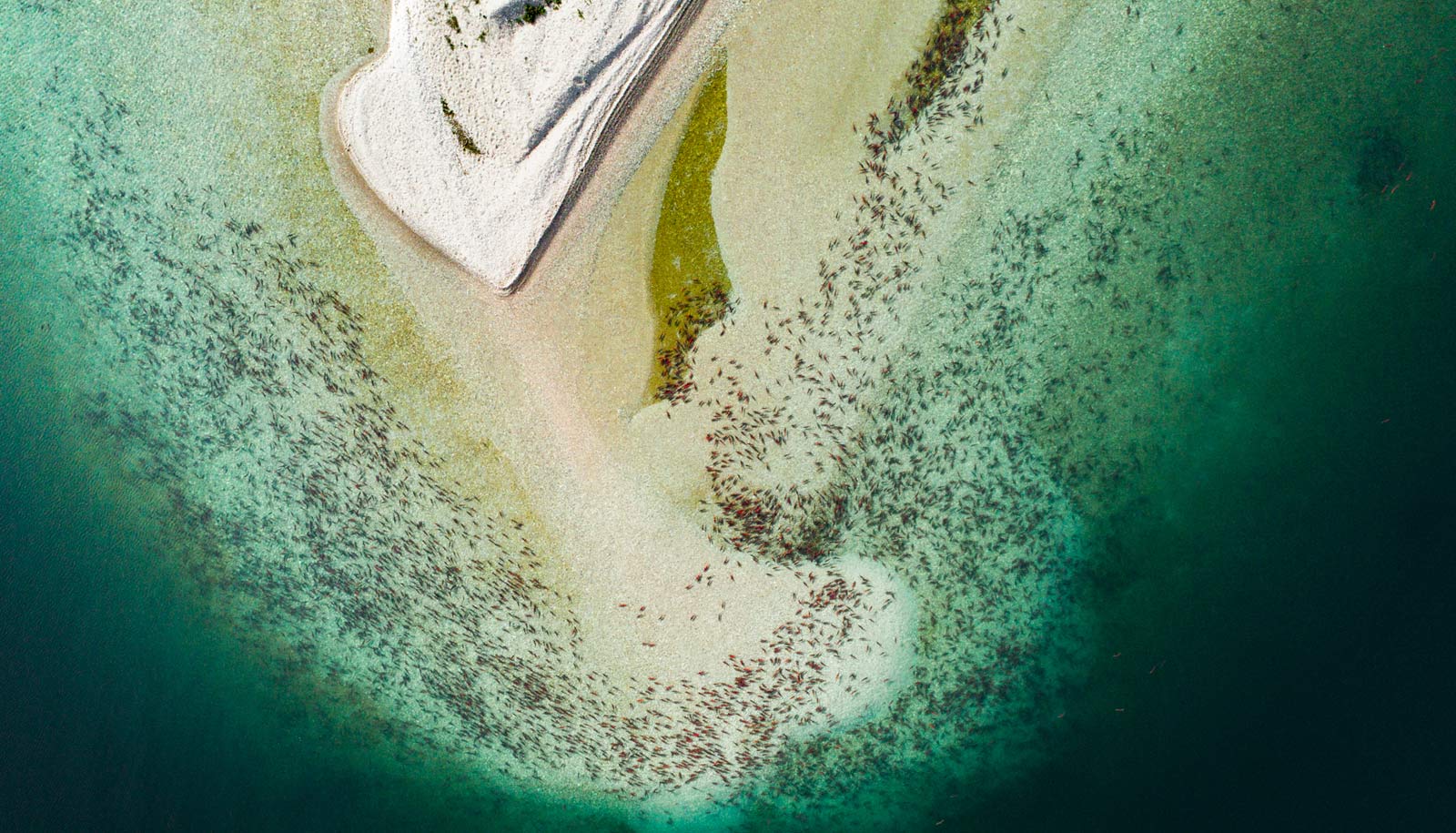

Hundreds of harbor seals live in the lake, the largest body of freshwater in Alaska and one of the most productive systems for sockeye salmon in the Bristol Bay region.

Although how the seals first colonized the lake remains a mystery, it is thought that sometime in the distant past, a handful of harbor seals likely migrated from the ocean more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) upriver to the lake, where they eventually grew to a consistent group of about 400. These animals are important for Alaska Native subsistence hunting, and hold a top spot in the lake’s diverse food web.

Scientists now know these “colonizing” seals must have found the lake suitable enough to stay and raise their offspring. Generations later, the lake-bound seals appear to be a genetically distinct population from their ocean-dwelling cousins—even though they are still managed as part of the larger Eastern Pacific harbor seal population.

But if the lake seals are distinct and show signs of local adaptation to their unique ecological setting, this would mean that their conservation—especially in the face of the rapidly changing climate of western Alaska and proposed industrial developments—should differ from that of nearby marine populations.

Lake seals vs. ocean seals

Lifelong chemical records stored in their sequentially growing canine teeth show that the Iliamna Lake seals remain in freshwater their entire lives, relying on food sources produced in the lake to survive.

In contrast, their relatives in the ocean are opportunistic feeders, moving around to the mouths of different rivers to find the most abundant food sources, which includes a diverse array of marine food items in addition to the adult salmon returning to Bristol Bay’s nine major watersheds. These findings appear in the journal Conservation Biology.

“We clearly show these seals are in the lake year-round, throughout their entire lives,” says lead author Sean Brennan, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences. “This gives us critical baseline information that can weigh in on how we understand their ecology, and we can use that information to do a better job developing a conservation strategy.”

Mining vs. critical habitat

This new study comes at a time when federal agencies are considering whether to permit mining activities in Bristol Bay, a region teeming with wildlife, including Alaska sockeye salmon. Iliamna Lake, with its resident seals and other animals, is located in the heart of the proposed Pebble Mine project.

The US Army Corps of Engineers this spring released a draft environmental impact statement that analyzes the project’s proposal, presents alternative plans, and gives the public a chance to comment. Ultimately, the document will help decide whether the controversial mine is approved.

Because of their current conservation status, the Iliamna Lake harbor seals aren’t assessed as a distinct and ecologically significant population in the project’s draft environmental impact analysis. If the seals are determined to be a distinct population, that has important implications for management of the Iliamna Lake system, the study’s authors say. The lake and its resident fishes would then be considered critical habitat for seals.

Separately, federal regulators have considered whether the lake seals should be named a distinct population, but scientists have been unable to agree on whether the seals are both distinct, and ecologically and evolutionarily significant, mainly because little is known about their ecology—including whether adult lake seals potentially migrate to the ocean to feed each year.

Seal teeth

Brennan was a doctoral student at the University of Alaska Fairbanks when he heard about early efforts to evaluate whether the lake seals were a distinct population. Chemical tracing methods he was using to track the life patterns of salmon could also work for the seals, he realized.

“The light just went off in my head,” Brennan says. “What I was doing for salmon was directly applicable to this population of seals.”

Brennan and collaborators looked at the chemical signatures present in the teeth of lake seals during each year of their life to better understand where they moved and what they ate. Specifically, the scientists drilled into the growth lines of the seals’ canine teeth, then measured the ratio of heavy and light isotopes of carbon, oxygen, and strontium present in each growth layer.

Because of the young bedrock geology of the Kvichak (QUEE-jak) River watershed, which encompasses Iliamna Lake, strontium isotope levels in the ocean are consistently much higher than in the lake. Unlike other elements, strontium signatures in mammal teeth directly reflect what animals assimilate from their environment, in particular, what they eat. Therefore, by looking at the strontium isotope ratios over the course of a seal’s life, the researchers saw that the ratios were consistent with lake signatures—meaning these seals only live in Lake Iliamna, depend principally on fish produced within the lake, and do not migrate to the ocean.

They also determined that young seals eat very little adult sockeye salmon. But later in life, the seals shift to supplement their diets with the seasonally abundant sockeye salmon that return each summer to the lake.

River dolphins next?

The researchers say this method could be used to better understand the life patterns of other elusive mammals around the world, such as river dolphins in the Amazon or the Mekong Basin. Broadly, marine mammals in coastal regions are among the most endangered animals on Earth, Brennan says.

“In terms of the broader picture of aquatic mammal conservation across the globe, I think we show that strontium isotopes can be really powerful because they collapse a lot of uncertainty. This method is completely underutilized across the world,” Brennan says.

Coauthors of the study are from the University of Washington, the University of Utah, and the University of Alaska Anchorage.

Funding for the study came from Alaska Sea Grant, Arctic-Yukon-Kuskokwim Sustainable Salmon Initiative, North Pacific Research Board, Bristol Bay Regional Seafood Development Association, and Bristol Bay Science Research Institute.

Source: University of Washington