A new map of the activities of seafloor invertebrate animals across the entire ocean reveals for the first time critical factors that support and maintain the health of marine ecosystems.

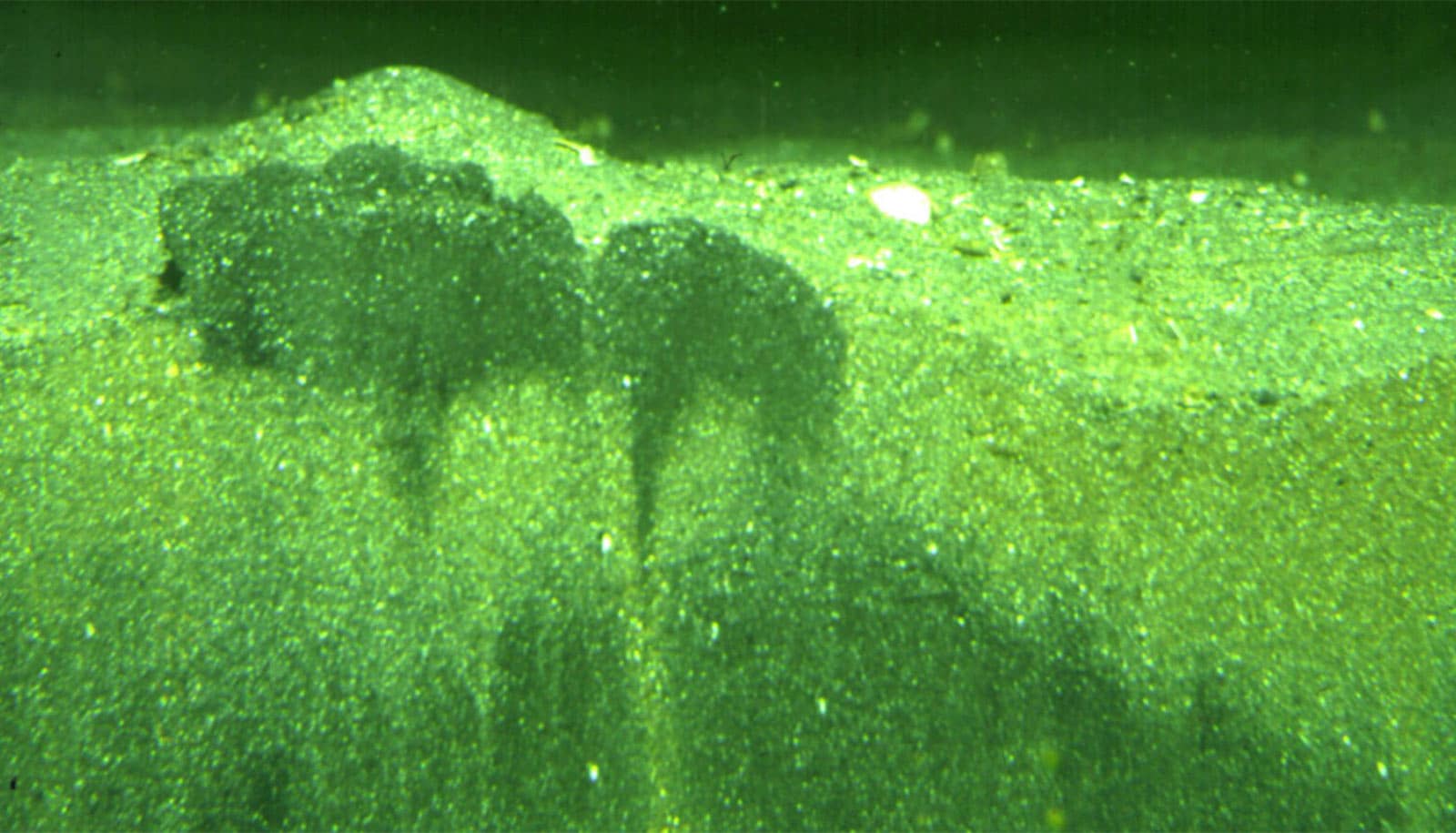

The researchers specifically focused on the unsung yet vital role burrowing animals, including worms, clams, and shrimps, play as “ecosystem engineers” in shaping nutrient cycling and ecosystem health—and, in turn, maritime economies and food security—throughout the oceans.

The researchers used machine learning to map out a global picture of these animals’ activities and the environmental conditions that drive them.

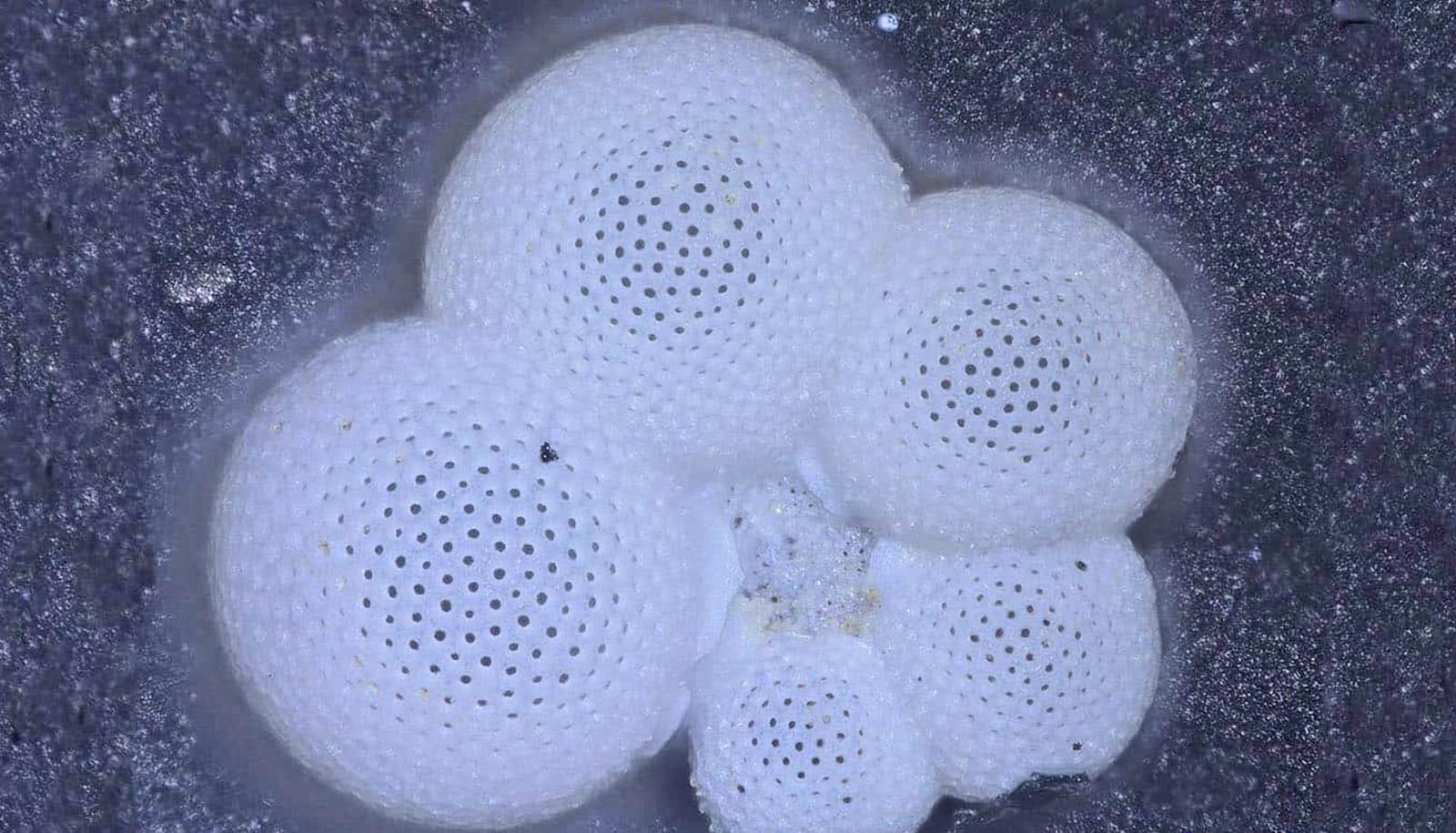

Marine sediments cover the majority of the Earth’s surface and are extremely diverse. By stirring up and churning the seafloor—a process known as bioturbation—seafloor invertebrates play a significant role in regulating global carbon, nutrient, and biogeochemical cycles, says Shuang Zhang, an assistant professor in the oceanography department at Texas A&M University and first author of the study in the journal Current Biology.

“Knowing how bioturbation links to other aspects of the environment means that we are now better equipped to predict how these systems might change in response to climate change,” says Zhang, who is also a member of the CArbon Cycle and Earth Environment (CACEE) Lab at Texas A&M.

Working with trained models and global datasets of bioturbation, the team factored in seawater depth, primary productivity, sediment type, and other criteria to investigate how the ocean environments in which these animals live influence how intensively and deeply mixed the seafloor is around the world.

“Through our analysis, we discovered that not just one, but multiple environmental factors jointly influence seafloor bioturbation and the ecosystem services these animals provide,” says Lidya Tarhan, an assistant professor in the Earth and planetary sciences department at Yale University.

“This includes factors that directly impact food supply, underlying the complex relationships that sustain marine life, both today and in Earth’s past.”

In addition to showing that current efforts to protect marine ecosystems have fallen short by not targeting these animals, the researchers note that their study has important ramifications for how we protect and conserve the ocean.

“We have known for some time that ocean sediments are extremely diverse and play a fundamental role in mediating the health of the ocean, but only now do we have insights about where, and by how much, these communities contribute,” says Martin Solan, a professor of marine ecology at Southampton University. “For example, the way in which these communities affect important aspects of ocean ecosystems are very different between the coastlines and deep sea.”

The ability to anticipate these changes is vital for developing strategies to mitigate habitat deterioration and protect marine biodiversity, Tartan says.

“Our analysis suggests that the present global network of marine protected areas does not sufficiently protect these important seafloor processes, indicating that protection measures need to be better catered to promote ecosystem health.”

The team is already planning their next joint collaboration, building on the findings of the present study. Despite having a clearer picture of geographic patterns in bioturbation, Zhang says major questions remain regarding how this translates into the many ecosystem services society relies upon, such as food security, climate regulation, and biogeochemical cycling.

Ultimately, Zhang asserts that researchers need to determine how best to protect seafloor communities and anticipate how these communities respond to a changing climate.

“Tackling these really big questions is vital, but as we have established here, it requires an international team with a diversity of expertise to fully address these problems,” Zhang adds. “By working together as we have done here, we expect additional exciting findings shortly.”

The Natural Environment Research Council and Yale University funded the work.

Source: Texas A&M University