The witchcraft accusations that roiled Salem, Massachusetts, in 1692 turned into one of the most notorious and mysterious miscarriages of justice in American history.

Digital mapping now reveals a possible starting point for the frenzy: the home of an embattled local reverend.

In his new book, Satan and Salem: The Witch-Hunt Crisis of 1692 (University of Virginia Press, 2015), Benjamin Ray, a religious studies professor at the University of Virginia, builds the most accurate picture to date of when and how Salem’s witchcraft accusations spread.

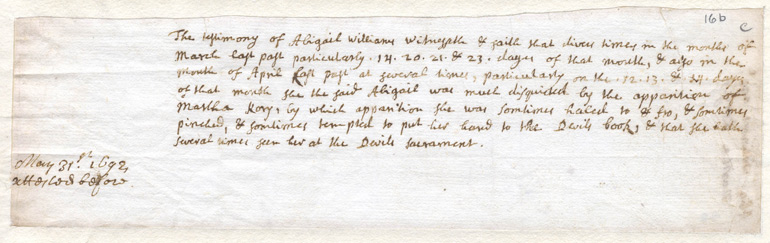

The university’s Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription project, the most comprehensive digital archive of primary source materials available on the trials, documents his case.

Ray led the development of the archive and used it to digitally map the geography and timing of each accusation. What he found led him to reconsider traditional assumptions about the origins of the frenzy.

“No other study has really looked to see how it developed incrementally and who the players were,” he says. “I realized that there was something still to be said, perhaps a new narrative, a new story.”

Satan’s target

The map, which Ray developed through Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, shows the initial witchcraft accusations beginning around the home of the Rev. Samuel Parris and tracks how accusations spread as the hysteria built.

Various sparks have been posited over the years, ranging from worry over impending attacks by Native Americans to tensions built on deep-seated economic inequality.

Ray’s mapping enabled him to examine both theories and ultimately regard them as potential contributing factors, but not primary causes. Instead, he used a microscopic focus on geography to pinpoint the epicenter of the accusations—a field directly beside the Parris home.

“Satan’s target,” Ray says, “was not just a few individuals, but ultimately the church itself.” That is what proved so alarming. The alleged witches were accused of trying to establish their own counter-church of Satan by repeatedly holding satanic masses (in spectral form) next to the village parsonage in a brazen attempt to supplant the Christian faith. Only the afflicted accusers and those who confessed could see them.

Parris came to the village shortly before the accusations began and faced immediate opposition when he issued a new declaration that sacraments, including baptism, could not be given to families who were not fully members of the church. Two or three generations removed from Salem’s ardently Puritan founders, some in the village did not want the hefty requirements of church membership, but still wanted baptism for their own and their children’s salvation.

This population of non-church members began a groundswell of opposition to Parris, leading a portion of the village to stop paying his salary and even cut off his firewood supply in October 1692 as the cold of a Massachusetts winter began to set in.

Seeing witches

Unsurprisingly, it was around this time that Parris began to accuse the devil of tearing down his church. After about a month of ominous warnings from the pulpit, the first witchcraft accusations ignited in Parris’ own household, when his 9-year-old daughter Betty and 11-year-old niece Abigail Williams and other young female accusers alleged that witches were meeting in the field adjacent to his house.

“Parris has been preaching about the devil, there are emergency meetings of church elders because his salary is cut off, he has to petition the government to force the village to pay him,” Ray says. “There is a lot of agitation in his house; the young, impressionable kids absorb it all, and it is not surprising that they begin to freak out.”

What was more puzzling to Ray was how the accusations grew from this localized dispute over church doctrine to the spiraling frenzy that left more than 150 people accused and 19 innocents dead by hanging. This was especially surprising given that the girls’ accusations ended a roughly 30-year lull in witchcraft accusations in New England at a time when Europe was executing “witches” by the thousands.

[related]

Again returning to digital mapping, Ray watched the accusations spread. Most of the accusers were daughters of church members, while most of the accused were outside of the church, supporting his theory that religious difference was the primary catalyst of the entire episode. He also noticed that accusations began to leap to Andover, Reading, and other villages in the region with the same message that Satan was not just trying to destroy Parris’ church, but the church as a whole.

“Now, the central institution of Puritan society, the church, was under attack, not just in Salem Village but all through Massachusetts,” he says. “Salem Village was ground zero and you can see the spreading alarm.”

As another of Ray’s interactive maps demonstrates, the spread of witchcraft hysteria was not unlike that of today’s media sensations. Fear of the devil’s presence essentially went viral in Salem, snowballing from a local dispute to a regional crisis.

“There is a kind of fanaticism here that is both of church and state, because of fear,” Ray says. “This is not the only time that it has happened in American history; in fact, it becomes a kind of an American paradigm.”

Source: University of Virginia