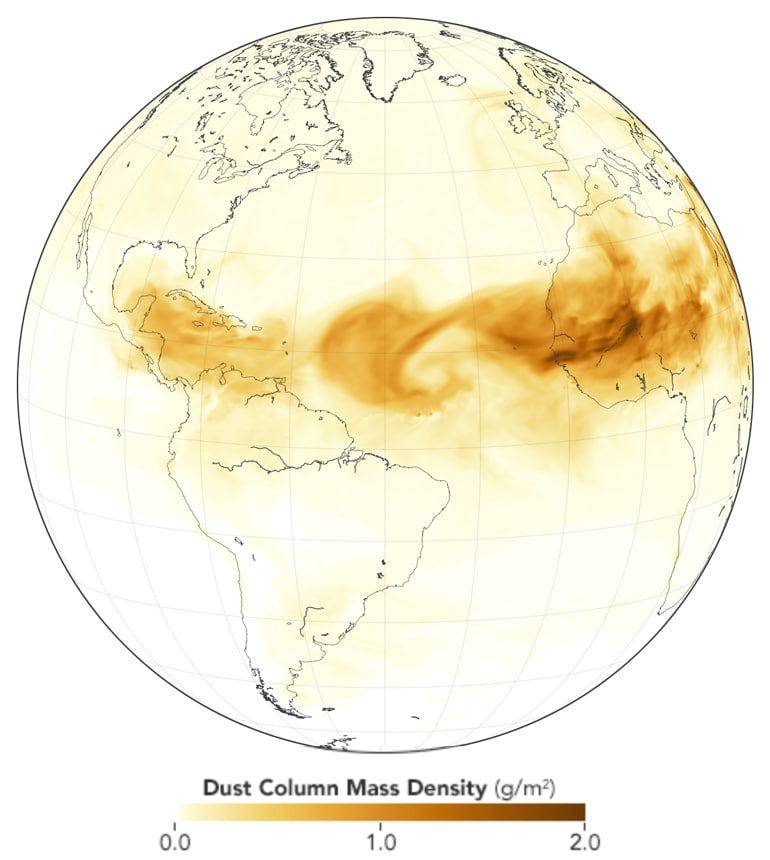

Although dust from the Sahara Desert in Africa—totaling a staggering 2 to 9 trillion pounds worldwide—has been almost a biblical plague on Texas and much of the Southern United States in recent weeks, it also appears to be a severe storm killer.

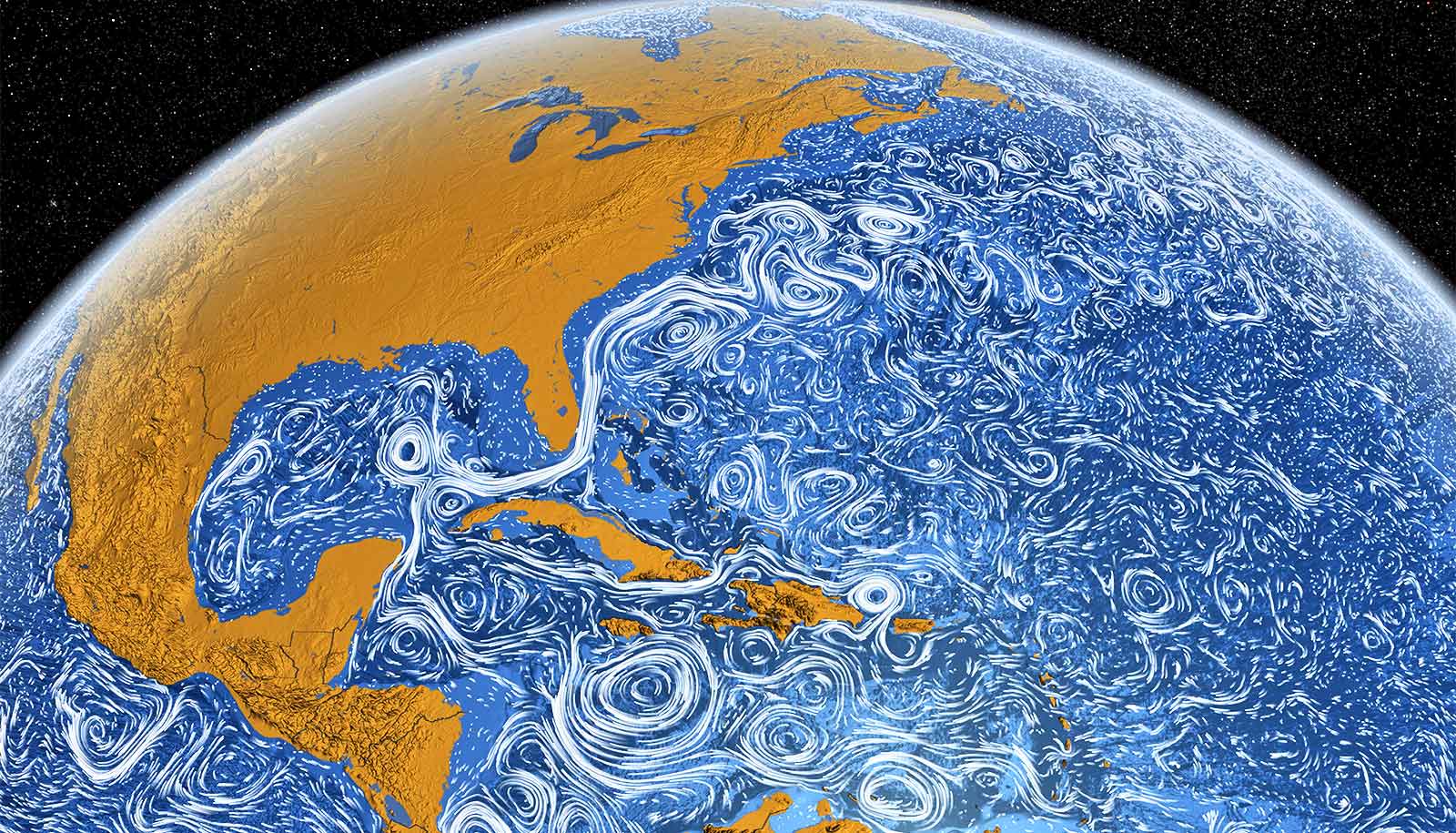

Bowen Pan, Tim Logan, and Renyi Zhang in the Texas A&M University’s department of atmospheric sciences analyzed recent NASA satellite images and computer models and say the Saharan dust contains sand and other mineral particles that air currents sweep up and push over the Atlantic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico and other nearby regions.

As the dust-laden air moves, it creates a temperature inversion that in turn tends to prevent cloud—and eventually—storm formation. That means fewer storms and even hurricanes are less likely to strike when the dust is present.

“The Saharan dust will reflect and absorb sunlight, therefore reduce the sunlight at the Earth’s surface,” says Pan. “If we have more frequent and severe dust storms, it’s likely that we have a cooler sea surface temperature and land surface temperature. The storms have less energy supply from the colder surface therefore will be less severe.”

The study, published in the Journal of Climate, goes on to show that dust and storm formation don’t mix.

“Our results show significant impacts of dust on the radiative budget, hydrological cycle, and large-scale environments relevant to tropical cyclone activity over the Atlantic,” says Zhang.

“Dust may decrease the sea surface temperature, leading to suppression of hurricanes. For the dust intrusion over the past few days, it was obvious that dust suppressed cloud formation in our area. Basically, we saw few cumulus clouds over the last few days. Dust particles reduce the radiation at the ground, but heats up in the atmosphere, both leading to more stable atmosphere. Such conditions are unfavorable for cloud formation.”

Climate change made Harvey’s rainfall more intense

Zhang says that the chances of a hurricane forming tended to be much less and “our results show that dust may reduce the occurrence of hurricanes over the Gulf of Mexico region.”

Logan says that recent satellite images clearly show the Saharan dust moving into much of the Gulf of Mexico and southern Texas.

“The movement of the dust is there,” Zhang says, “but predictions of dust storms can be very challenging.”

NASA funded the work.

Source: Texas A&M University