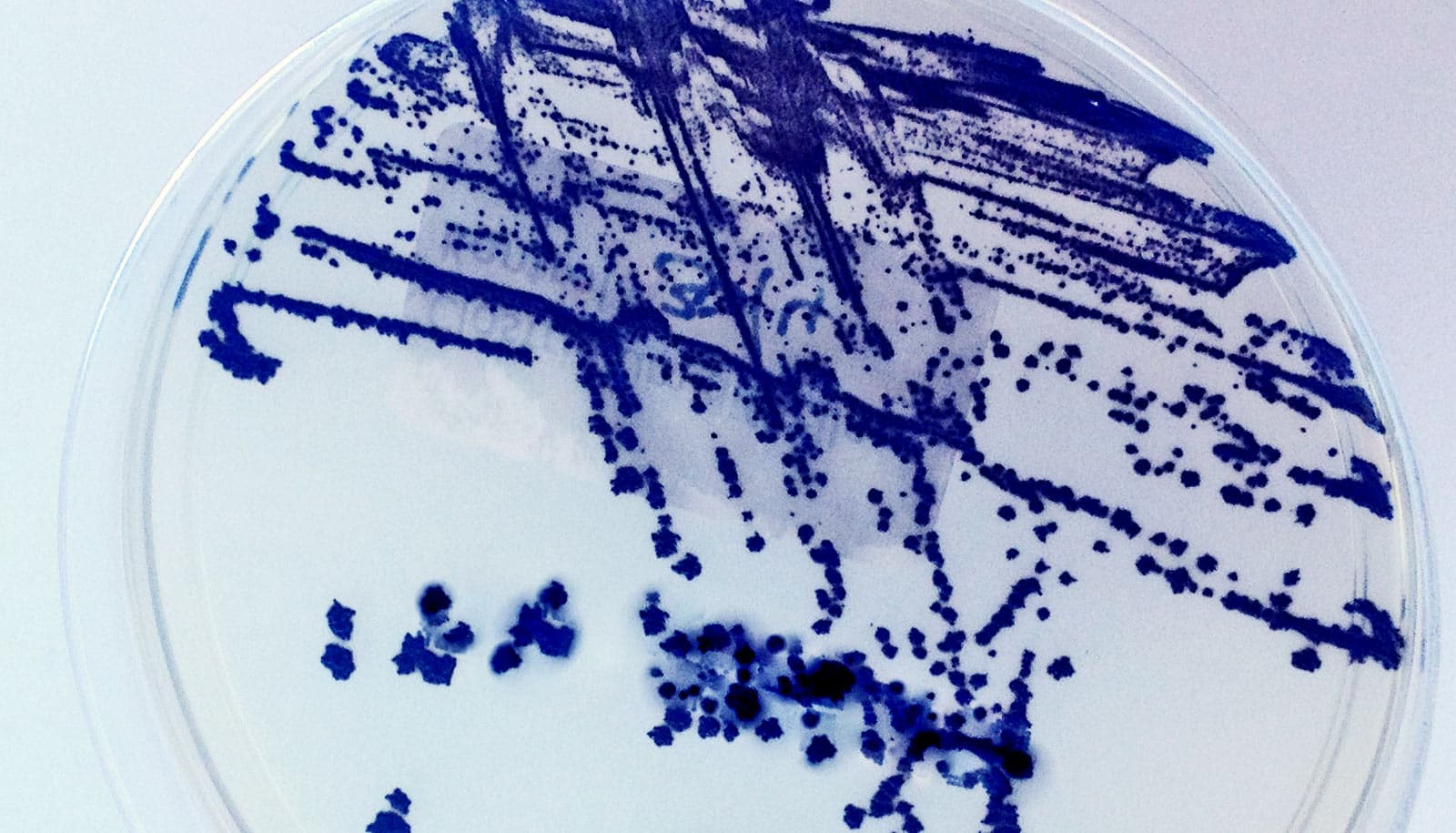

Colon operations come with special risks because the colon teems with microbes that can cause havoc if they escape during or after surgery.

But a new study points to a way to reduce the risk of infections after colectomies for the hundreds of thousands of Americans who have such operations each year because of cancer, polyps, diverticulitis, or inflammatory bowel disease.

The approach was associated with a nearly 50 percent reduction in surgical site infections over four years among 5,742 patients who had colectomies at 52 Michigan hospitals. A team from the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative and the University of Michigan Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation report the findings in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

The study gives new support to a low-cost, “bottom-up,” grassroots approach to preventing surgical site infections.

3 infection-reducers

The effort used a collaborative, voluntary, evidence-driven approach to encourage hospitals to change three steps that patients and providers take before, during, and after colectomy.

Previous work had shown that these three steps were underused, despite strong evidence of their potential to reduce infection:

- A thorough emptying of the lower digestive system by patients in the days before surgery, using medication and a liquid diet similar to what’s prescribed before a colonoscopy, and adding antibiotic pills that can tamp down infection

- Intravenous doses of two antibiotics—cefazolin and metronidazole—during surgery, to reduce infection risk while also posing the lowest chance of encouraging drug-resistant bacteria

- Getting patients’ blood sugar levels back to normal (around 140 milligrams per deciliter) on the first day after surgery

All three steps, which are inexpensive and relatively easy to take, had shown value in previous Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative studies of data from dozens of hospitals, as part of its quality-improvement effort that the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan funded.

Two other factors—offering laparoscopic instead of open operations and shorter operation times—also emerged as key factors in reducing surgical site infections, but they are not as easy to control.

Getting closer

The hospitals were far from perfect in adopting the three practices.

Only 32 percent of patients were receiving the intravenous antibiotics by the end of the study period (up from 18 percent), and 62 percent were prescribed the bowel prep and oral antibiotics, up from 43 percent. The percentage of patients whose blood sugar levels were brought back to normal rapidly did not increase. The researchers did not determine what percentage of patients successfully completed the bowel preparation that they had been prescribed.

But still, over the four years, rates of post-surgery complications dropped from 5.7 percent of patients to 1.1 percent. Sepsis rates decreased from 4.6 percent of patients to 1.1 percent. Patients also had far fewer repeat operations and hospital stays.

Implementing the three practices meant changing office and operating room workflows as well as individuals’ customs—and sharing best practices hospital-to-hospital.

“Sharing of best practices among hospitals promotes and accelerates the process, and for complex problems, collaboration among hospitals fosters learning and discovery on a level that is difficult to achieve at a single hospital,” says Greta Krapohl, associate director of the collaborative and a research investigator in the University of Michigan department of surgery.

Will swallowing microbes replace the colonoscopy?

When the researchers looked at the entire surgical site infection bundle—including the three steps that were emphasized, plus body temperature normalization, laparoscopic surgery, and duration—they found that 1.6 percent of patients treated using five or six steps developed infections, compared with 6.2 percent of patients treated using none of the steps or just one.

Better for patients and budgets

Besides sparing patients the misery of a surgical site infection and complications, the effort may have cut costs.

Every colectomy site infection increases the cost of a patient’s care by about $18,000—and the Medicare system now penalizes hospitals financially if their rates of such infections are higher than average. Other payers are also emphasizing better outcomes and reduced complications.

The race to get below average on colon surgical site infections has intensified, and the Michigan collaborative’s participating hospitals get frequent updates on how their performance compares with the others.

Fiber in food may protect the gel in your gut

But this approach leaves it to hospitals to determine whether and how to implement its guidelines within their institution’s culture and organizational structure.

The team had previously shown, in a look back at medical and billing records, that infections and costs were lower among patients who had a colectomy at one of the hospitals that did the best at sticking to the six elements of the “bundle.”

Source: University of Michigan