The rate of ice mass loss in the Russian Arctic has nearly doubled over the last decade when compared to records from the previous 60 years, a new study shows.

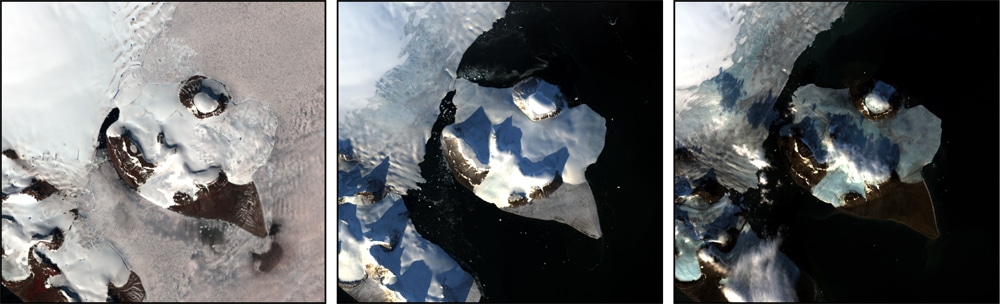

Scientists focused on Franz Josef Land, a glaciated Russian archipelago in the Kara and Barents seas—among the northernmost and most remote parcels of land on Earth, using very high-resolution optical satellite images to examine the island group’s glacial dynamics.

“Glaciers there are shrinking by area and by height. We are seeing an increase in the recent speed of ice loss, when compared to the long-term ice-loss rate,” says lead researcher Whyjay Zheng, a doctoral student in geophysics at Cornell University.

The shrinking glaciers have uncovered at least one new island.

As reported in Remote Sensing of Environment, from 1953 to 2010, the average rate of ice surface loss was 18 centimeters (7.1 inches) per year. From 2011 to 2015, the ice surface decrease was 32 centimeters (13 inches) per year, which is a water loss of 4.43 gigatons annually, Zheng says.

For perspective, that much water would raise the level of Cayuga Lake (the longest of New York state’s Finger Lakes, at 38 miles) by 85 feet and inundate nearby cities of Ithaca and Seneca Falls.

The Arctic has been warming in recent decades, but glaciers across the region are responding in different ways.

“Previous studies have shown that the glaciers in northern Canada seem to be shrinking at a faster rate than the ones in some parts of northern Russia,” says senior author Matt Pritchard, professor of geophysics.

Climate cuts number of trash-eating Arctic bugs

“Our work takes a closer look at the Russian glaciers to understand why they might be responding to a warming Arctic differently than glaciers in other parts of the Arctic. Why glaciers in Franz Josef Land have been shrinking more rapidly between 2011 and 2015 than in previous decades is possibly related to ocean temperature changes.”

A scientific dictum states glacier change should happen slowly in the Arctic because temperatures are low, the ice is very cold, and it melts more slowly than ice elsewhere.

“We are finding out that the ice is changing more rapidly than we previously thought,” Zheng says. “The temperature is changing in the Arctic faster than anywhere else in the world.”

Snow on Arctic sea ice continues to thin

Coauthors are from the University of Colorado; the University of Edinburgh, Scotland; the Université de Strasbourg, France; and the University of Cambridge, England.

An Overseas PhD Scholarship funded by the Ministry of Education, Taiwan, funded Zheng’s work.

Source: Cornell University