A new way to deliver antibodies directly to the lungs could help children ward off respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), according to new research.

RSV sends some 57,000 US children younger than 5 to the hospital each year. There’s no vaccine for the virus, which usually only causes cold-like symptoms. Medications doctors sometimes use to prevent it in high-risk children aren’t always effective.

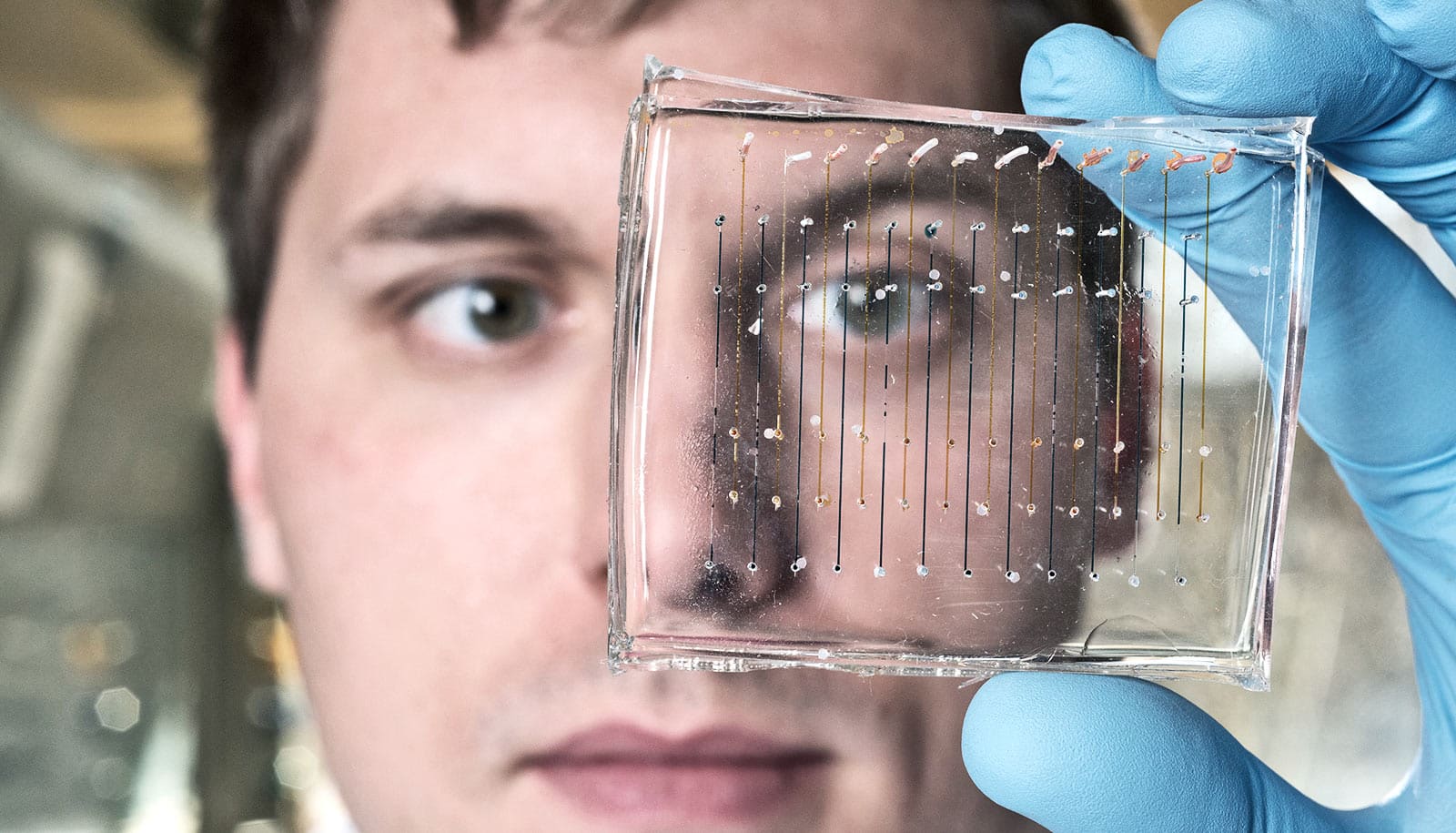

The new method was a natural outgrowth of research in his lab, says Philip Santangelo, associate professor in the biomedical engineering department at Georgia Tech and Emory University. That research focused on using RNA to deliver therapeutic antibodies, as well as with the basic virology of RSV. He says combining the two was “a logical choice.”

Doctors give one of the medications they use to treat or prevent RSV, the monoclonal antibody palivizumab, monthly via intramuscular (IM) injection, but only a small amount of the antibody gets into the airways.

“RSV tends to infect airway epithelial cells, as does flu,” Santangelo says. “We really didn’t see palivizumab there in large quantities. So we thought that was an opportunity.”

Direct delivery

As reported in Nature Communications, researchers used synthetic messenger RNA (mRNA) to deliver antibodies directly to the lungs of mice via aerosol, which the study shows protected them from RSV infection.

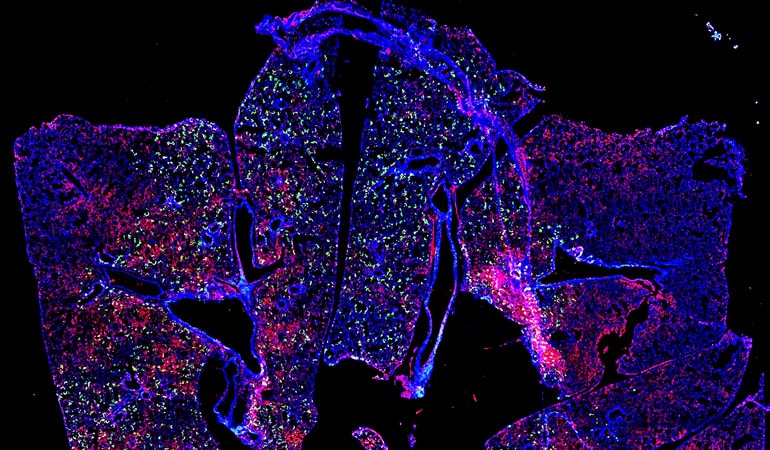

The researchers used two forms of palivizumab, the whole secreted form (sPali) and one that they engineered with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) membrane anchor or linker (aPali), which should allow it to stay on the epithelial surface longer.

They treated another group of mice with a different antibody—a VHH camelid antibody, also in secreted and anchored forms—that previous research showed to be more potent than palivizumab but is not currently used to treat RSV.

“With palivizumab, that may or may not be as critical—we noticed that even with the secreted version we were able to block the virus reasonably well,” Santangelo says.

“But single-chain antibodies, which are very small, have short half-lives. You have to give them frequently, which doesn’t seem practical. When we put this linker on the smaller antibody, we were able to see it on the epithelial cells 28 days later. That was really exciting to us,” he explains.

In fact, Santangelo suspects that using the linker could cause smaller antibodies to persist for a few months, reducing the need for frequent treatments. “You could see administering this right after a child is born, when they are most vulnerable,” he says.

“…if you could protect kids for a few months at a time, that’s really all you would need to do.”

Using mRNA is an effective and safe delivery option, especially crucial in a pediatric population.

“Using a transient, nucleic acid-based method that doesn’t end up in the cell nucleus is really important,” Santangelo says. “We do want this to be transient, so if it lasted even a month that would protect newborns in the hospital where they may be exposed to RSV. And if you could protect kids for a few months at a time, that’s really all you would need to do.”

The researchers found that most of the mRNA-expressed antibodies did not change baseline levels of cytokines, indicating that the approach was minimally inflammatory and suggesting that repeat dosing could be considered.

It’s also possible that the antibodies researchers used in this study could neutralize the virus in cells, so even if the virus had already infected a child, the delivery might lessen the severity of symptoms.

Beyond RSV

Further, RSV isn’t the only potential virus this method could target. Santangelo is currently working on a project that targets flu via dry powder delivery of mRNA.

With the promising results from the RSV study, Santangelo hopes to move from a mouse model to additional testing.

“There’s more work to be done,” he says. “The use of antibodies for preventing infection is a huge deal right now. But even if you found this potent antibody, if you can’t deliver it where it needs to go then the efficacy may not be where you want it to be.

“At least with the lung, we know where we want to go, and IV or IM administration isn’t really ideal for the cell types that are most critical for RSV,” he explains.

A Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency grant and Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta funded the work. The views, opinions, and/or findings expressed are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the US government.

Source: Georgia Tech