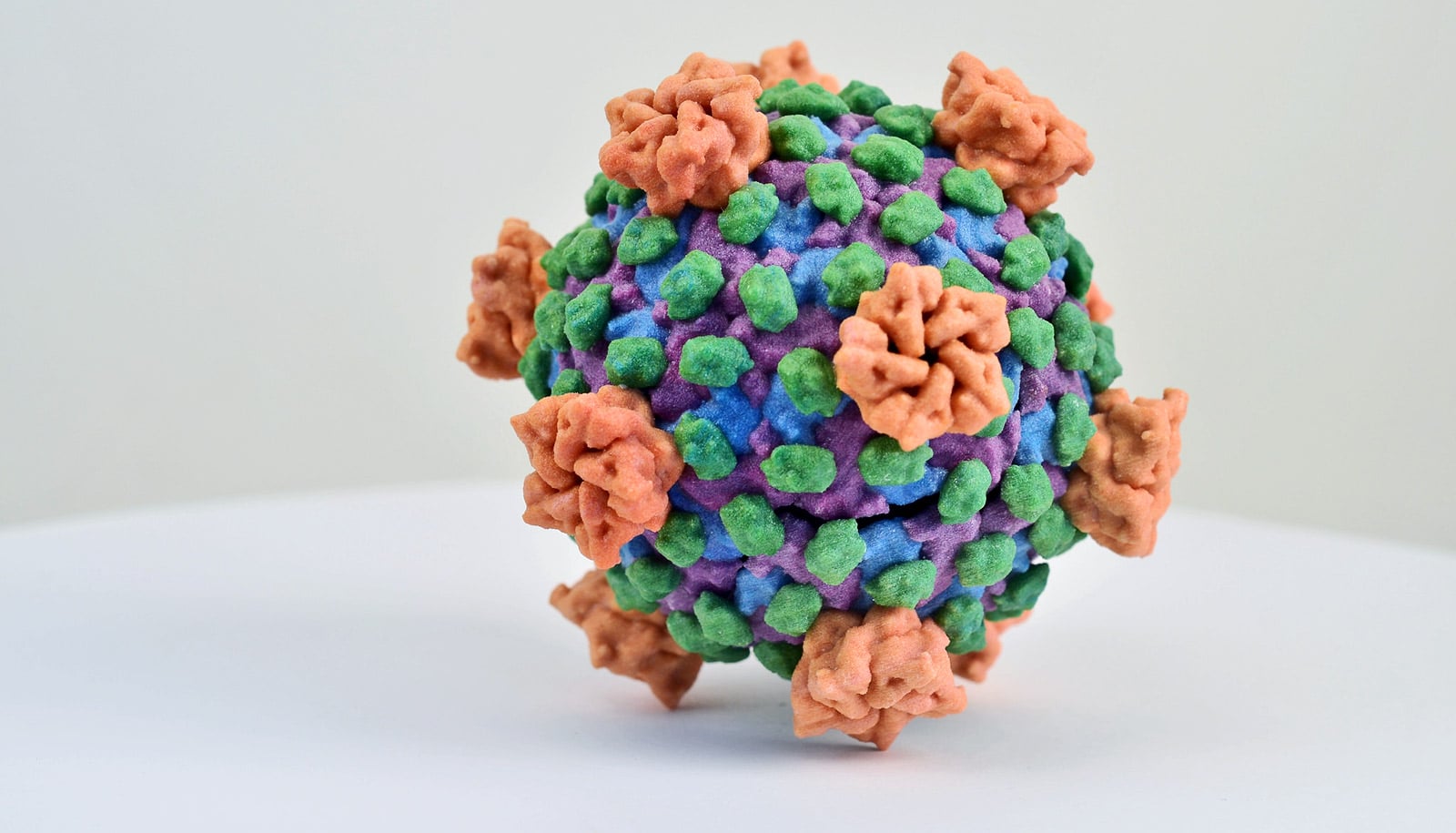

The presence of certain gut bacteria in the digestive tract can prevent and cure rotavirus infection in mice, research finds.

Rotavirus is the leading cause of severe, life-threatening diarrhea in children worldwide.

The findings, published in the journal Cell, may explain why rotavirus causes severe, life-threatening disease in some people and only mild disease in others. The work could lead to possible treatments and preventive measures for rotavirus infection. There are no existing treatments for rotavirus besides administering fluids to avoid dehydration.

Rotavirus is a highly contagious virus that can cause severe diarrhea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, and death. Rotavirus infection occurs as a result of direct contact with an infected person or exposure to their fecal matter. Infants and young children are the most susceptible to this disease, and the illness can lead to severe dehydration, hospitalization, or even death. Rotavirus leads to an estimated 215,000 deaths worldwide in children younger than 5 years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Susceptibility to rotavirus is not well understood and can vary vastly among individuals and regions. Rotavirus causes relatively mild disease in both developed countries and poor regions of central America, but it kills many thousands of children each year in poor regions of Sub-Saharan Africa and India. Even within particular societies, rotavirus causes mild disease in some individuals and severe life-threatening disease in others.

“This study shows that one big determinant of proneness to rotavirus infection is microbiota composition,” says Andrew Gewirtz, senior author of the study and a professor in the Institute for Biomedical Sciences at Georgia State University.

Gut microbiota is the collective term for microorganisms living in the intestinal tract. Microbiota composition was known to influence bacterial infection, but a role for microbiota in influencing viral infection was totally unknown.

“This discovery was serendipitous,” Gewirtz says. “We were breeding mice and realized that some of them were completely resistant to rotavirus whereas others were highly susceptible. We investigated why and found that the resistant mice carried distinct microbiota. Fecal microbiota transplant transferred rotavirus resistance to new hosts.”

Further investigation revealed that a predominant determinant of resistance to rotavirus was the presence of a single bacterial species called Segmented Filamentous Bacteria, or SFB. The researchers found SFB reduces rotavirus infectivity and protects against rotavirus by causing epithelial cells to shed and be replaced with new, uninfected cells.

“It’s a new basic discovery that should help understand proneness to rotavirus infection,” Gewirtz says. “It does not yield an immediate treatment for humans, but provides a potential mechanism to explain the differential susceptibility of different populations and different people to enteric viral infection. Furthermore, it may lead to new strategies to prevent and treat viral infections.”

First author Zhenda Shi who now works at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s rotavirus branch, is investigating whether or not gut microbiota can explain differences in sensitivity to rotavirus infection in humans.

Coauthors of the study are from Georgia State; Fudan University in Shanghai, China; Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; Washington University School of Medicine; Vanderbilt University School of Medicine; Oregon Health Sciences University; and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

Funding came from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Source: Georgia State University