A horse, a zebra, and artificial intelligence helped researchers teach a robot to recognize water and pour it into a glass.

Water presents a tricky challenge for robots because it is clear. Robots have learned how to pour water before, but previous techniques like heating the water and using a thermal camera or placing the glass in front of a checkerboard background don’t transition well to everyday life.

An easier solution could enable robot servers to refill water glasses, robot pharmacists to measure and mix medicines, or robot gardeners to water plants.

Now, researchers have used AI and image translation to solve the problem.

Image translation algorithms use collections of images to train artificial intelligence to convert images from one style to another, such as transforming a photo into a Monet-style painting or making an image of a horse look like a zebra. For this research, the team used a method called contrastive learning for unpaired image-to-image translation, or CUT, for short.

“You need some way of telling the algorithm what the right and wrong answers are during the training phase of learning,” says David Held, an assistant professor in the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University. “However, labeling data can be a time-consuming process, especially for teaching a robot to pour water, for which the human might need to label individual water droplets in an image.”

Enter the horse and zebra.

“Just like we can train a model to translate an image of a horse to look like a zebra, we can similarly train a model to translate an image of colored liquid into an image of transparent liquid,” Held says. “We used this model to enable the robot to understand transparent liquids.”

A transparent liquid like water is hard for a robot to see because the way it reflects, refracts, and absorbs light varies depending on the background. To teach the computer how to see different backgrounds through a glass of water, the team played YouTube videos behind a transparent glass full of water. Training the system this way will allow the robot to pour water against varied backgrounds in the real world, regardless of where the robot is located.

“Even for humans, sometimes it’s hard to precisely identify the boundary between water and air,” says Gautham Narasimhan, who earned his master’s degree in the Robotics Institute in 2020 and worked with a team in the institute’s Robots Perceiving and Doing Lab on the new work.

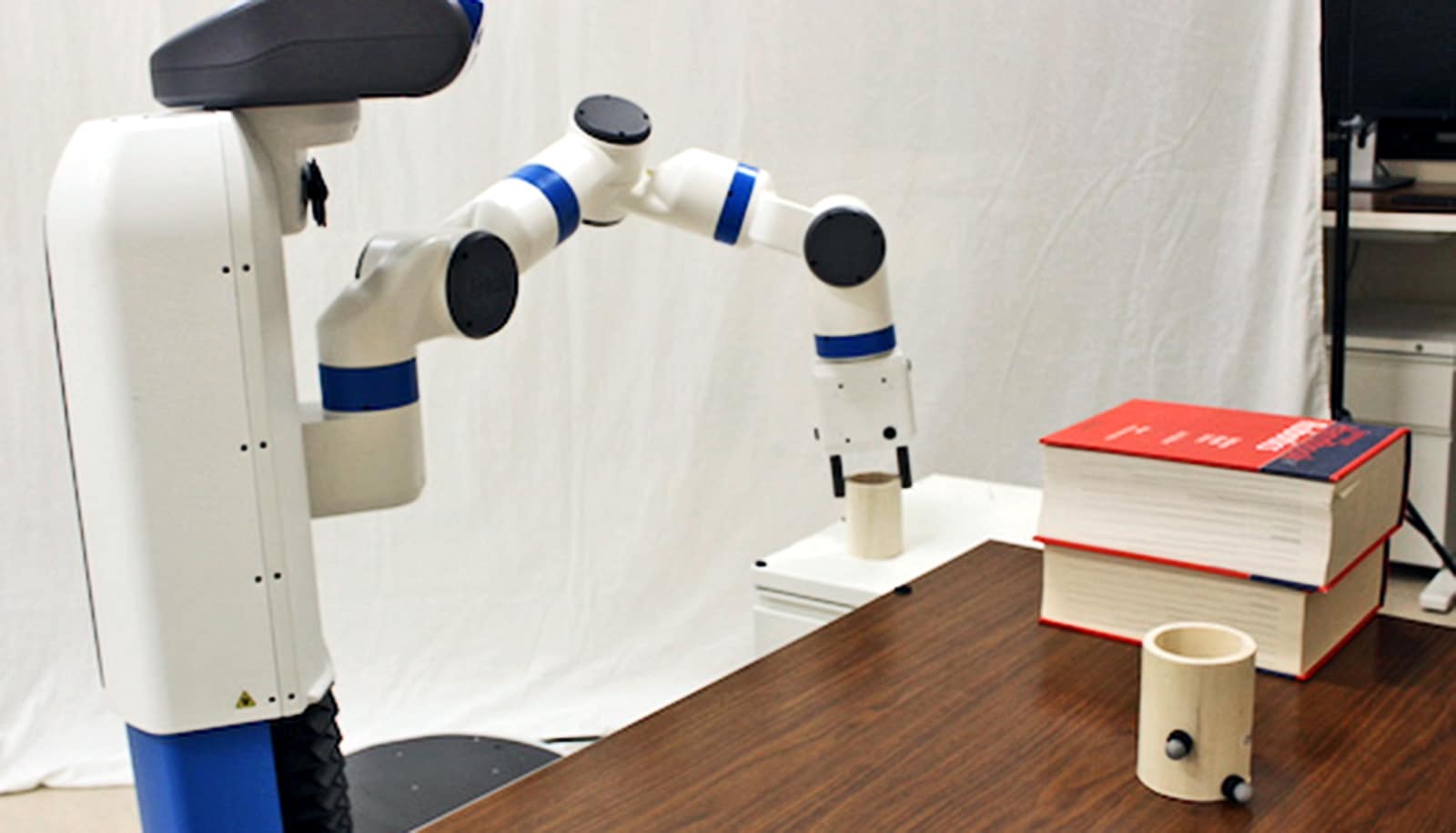

Using their method, the robot was able to pour the water until it reached a certain height in a glass. They then repeated the experiment with glasses of different shapes and sizes.

Narasimhan says there’s room for future research to expand upon this method—adding different lighting conditions, challenging the robot to pour water from one container to another, or estimating not only the height of the water, but also the volume.

The researchers presented their work at the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation in May 2022.

“People in robotics really appreciate it when research works in the real world and not just in simulation,” says Narasimhan, who now works as a computer vision engineer with Path Robotics in Columbus, Ohio. “We wanted to do something that’s quite simple yet effective.”

Funding for the work came from LG Electronics and a National Science Foundation grant.

Source: Carnegie Mellon University