Only about one-third, or 37 percent, of the world’s 246 longest rivers remain free-flowing, according to a new study.

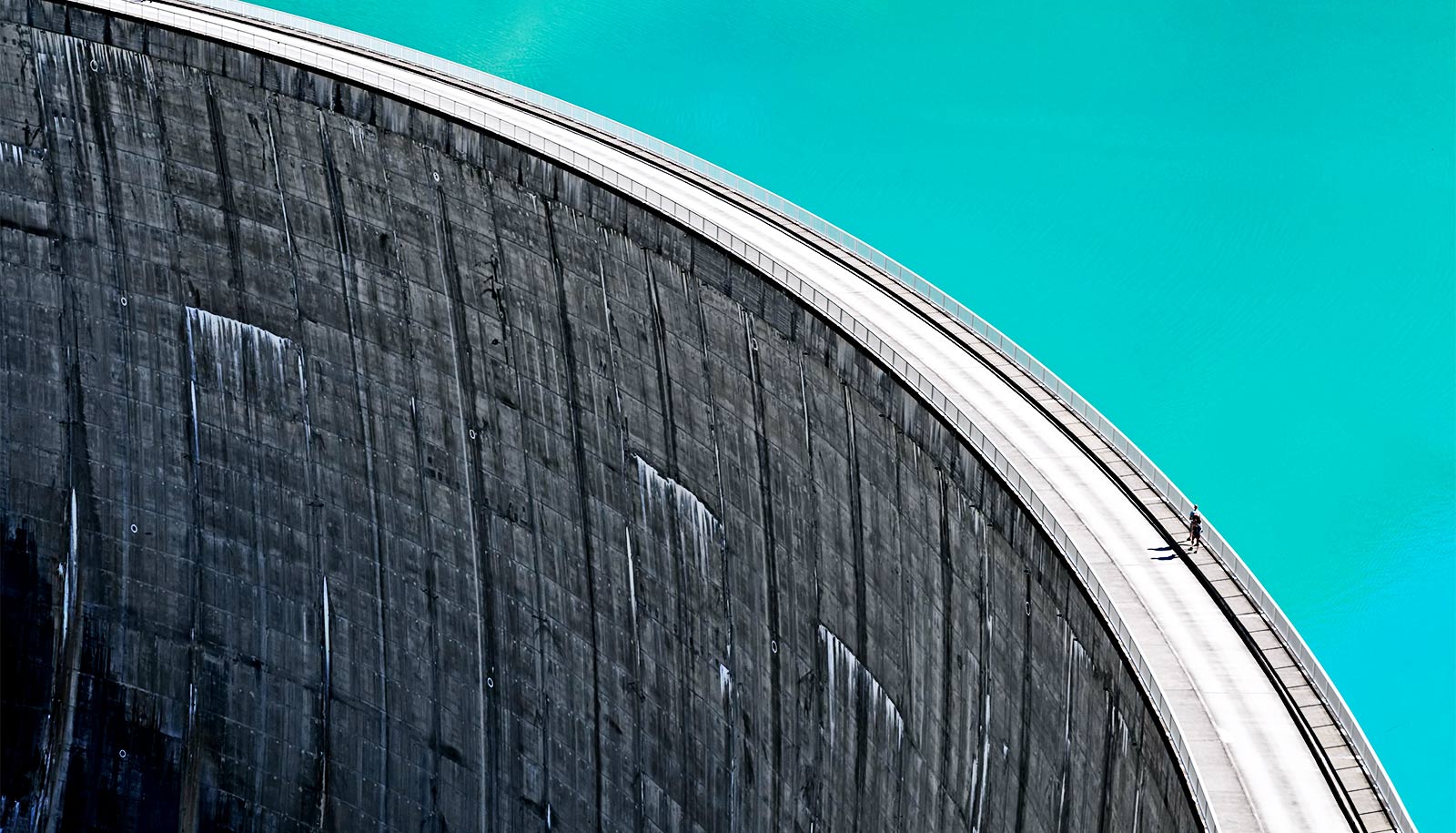

Dams and reservoirs are drastically reducing the diverse benefits that healthy rivers provide to people and nature across the globe.

Researchers assessed the connectivity status of 12 million kilometers (around 7.5 million miles) of rivers worldwide, providing the first ever global assessment of the location and extent of the planet’s remaining free-flowing rivers.

“The world’s rivers form an intricate network with vital links to land, groundwater, and the atmosphere.”

Among other findings, the researchers determined only 21 of the world’s 91 rivers longer than 1,000 kilometers (621 miles) that originally flowed to the ocean still retain a direct connection from source to sea. The planet’s remaining free-flowing rivers are largely restricted to remote regions of the Arctic, the Amazon Basin, and the Congo Basin.

“The world’s rivers form an intricate network with vital links to land, groundwater, and the atmosphere,” says lead author Günther Grill, a postdoctoral researcher in the geography department at McGill University.

”Free-flowing rivers are important for humans and the environment alike, yet economic development around the world is making them increasingly rare. Using satellite imagery and other data, our study examines the extent of these rivers in more detail than ever before.”

Dams and reservoirs are the leading contributors to connectivity loss in global rivers. The study estimates there are around 60,000 large dams worldwide, and more than 3,700 hydropower dams are currently planned or under construction. People often plan and build dams and reservoirs at the individual project level, making it difficult to assess their real impacts across an entire basin or region.

“This work has been made possible through more than a decade of data collection and preparation,” says Bernhard Lehner, an associate professor whose research team, including Grill and others, conducted the required computer simulations.

“We first needed to create digital maps of millions of rivers, lakes, and reservoirs on Earth so that we can now study the effect of human alterations on this complex system of connected waterways.”

Healthy rivers support freshwater fish stocks that improve food security for hundreds of millions of people, deliver sediment that keeps deltas above rising seas, mitigate the impact of extreme floods and droughts, prevent loss of infrastructure and fields to erosion, and support a wealth of biodiversity. Disrupting rivers’ connectivity often diminishes or even eliminates these critical ecosystem services.

“Our results reinforce the urgent imperative for concerted global and national strategies to maintain and restore river connectivity and free-flowing rivers around the world if we are to sustain freshwater species, river ecosystems and the services that they provide,” Grill says. “Our novel method to map free-flowing rivers provides a foundation to track and monitor their status, using a global dataset and tools that we are making publicly and freely available.”

The study also notes that climate change will further threaten the health of rivers worldwide. Rising temperatures are already impacting flow patterns, water quality, and biodiversity. Meanwhile, as countries around the world shift to low-carbon economies, hydropower planning and development is accelerating, adding urgency to the need to develop energy systems that minimize overall environmental and social impact.

“It is not about eliminating development,” says Lehner, “but about finding smart and sustainable solutions in which free-flowing rivers and humans can coexist. Prioritizing other energy sources such as wind and solar, improving dam operations, or identifying better dam locations may be part of these solutions.”

The international community is committed to protect and restore rivers under Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development, which requires countries to track the extent and condition of water-related ecosystems. This study delivers methods and data necessary for countries to maintain and restore free-flowing rivers around the world.

The study appears in Nature.

Additional researchers contributing to the project came from McGill University, WWF, the University of Basel, the Joint Research Centre, the Nature Conservancy, the University of Nevada, IHE Delft, HTWG Konstanz, King’s College London, Umeå University, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, the University of Washington, Harvard University, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Conservation International, Stanford University, Leibniz-Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries, Freie Universität Berlin, and Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen.

Funding for this study came from by World Wildlife Fund, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and McGill University.

Source: McGill University