The amount of ice in the Earth’s rivers has declined rapidly over the past three decades, and the trend is likely to continue, researches report.

Rivers that seasonably freeze over drain more than a third of the Earth’s land mass. Examining more than 400,000 satellite images over the past 34 years, researchers found that the overall amount of river ice has declined, and will almost certainly continue to do so as global temperatures continue to rise.

For every degree of increase in global temperature, there will be about 6 days less of ice per year on rivers that freeze, the researchers found.

“We found that 56% of Earth’s rivers are seasonally affected by river ice, which amounts to a much greater proportion of rivers than previously thought,” says George Allen, assistant professor of geography at Texas A&M University.

“We found that almost all the river ice is located in the Northern Hemisphere with only rivers in southernmost portions of New Zealand, Patagonia, and Australia. It is important to note that we only observed rivers with widths over 300 feet, so it is likely that there a lot of smaller rivers and streams that also freeze but we did not detect them.”

“…in many parts of the world, river ice plays important roles in transportation and in ecosystems.”

Rivers are natural hotspots for greenhouse gas emissions to the atmosphere, and these emissions typically slow down or completely stop when rivers freeze, Allen says. The finding that the occurrence of ice is declining suggests that the global river network contributes more and more to the atmospheric greenhouse gas emissions.

“The anticipated acceleration in the decline of river ice is not evenly distributed around the world,” Allen says. “In the United States, river ice is expected to decline most rapidly in the Rocky Mountains and in the Northeast.

“If you’ve lived in Texas for a long time, you probably haven’t thought that much about the importance of river ice,” Allen says. “However, in many parts of the world, river ice plays important roles in transportation and in ecosystems.

“For example, during the winter, many remote Arctic civilizations rely on frozen rivers as ice roads. In the spring, during river ice breakup, ice jams can cause unpredictable and hugely disruptive floods, but these floods actually benefit ecosystems by distributing nutrients across floodplains.”

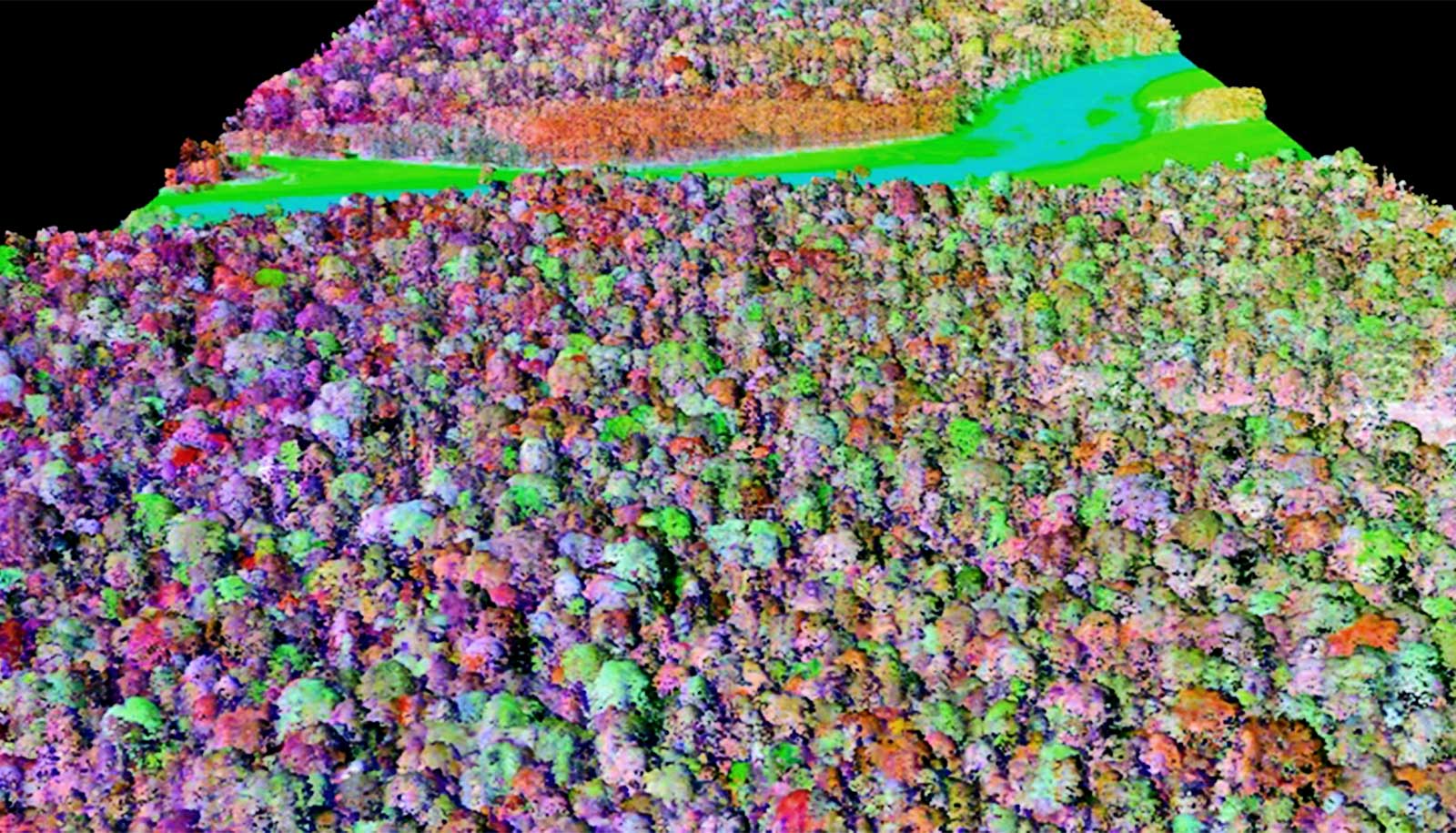

Two recent technological developments made the study possible, Allen says. One is the first global map of river location and width from optical satellite images, and the second is Google Earth Engine-provided cloud-based data that makes processing hundreds of thousands of satellite images relatively easy.

The study appears in Nature. Additional researchers are from the University of North Carolina. The NASA/CNES Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite mission, planned for launch in September 2021, funded the work. Researchers expect the mission will provide unprecedented observations of Earth’s rivers and lakes.

Source: Texas A&M University