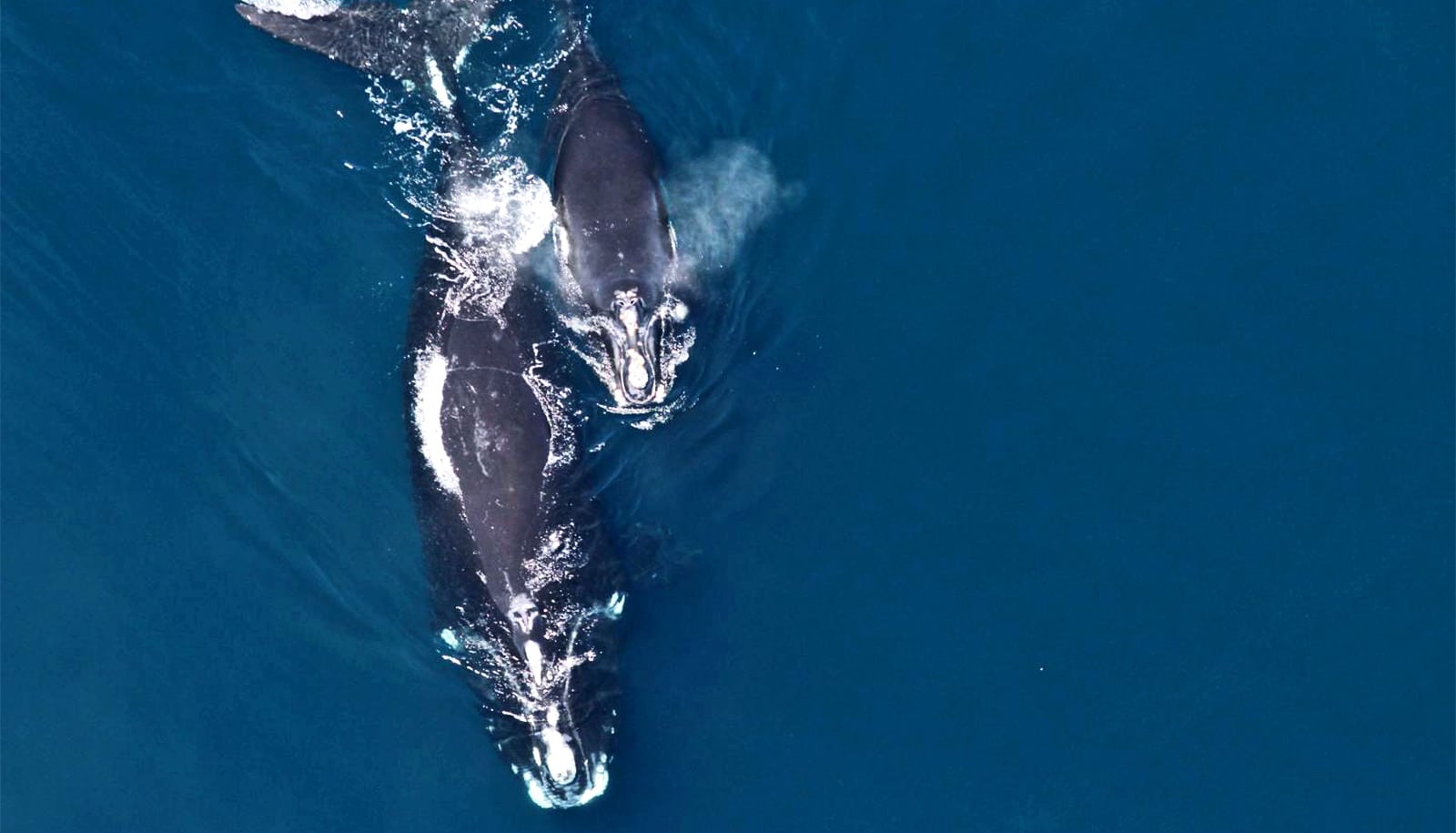

As new moms, North Atlantic right whales “whisper” to their young calves to avoid attracting predators, according to a new study.

The whales, which are critically endangered, have few natural predators due to their size, but their calves are vulnerable to orcas and sharks when young.

The study reveals the new mothers drastically reduce their production of a vocalization known as an “up call” that the species typically uses to communicate with other right whales. An up call produces a short, loud “whoop” sound that rises sharply, can travel long distances underwater, and lasts for up to two seconds.

“[These sounds] allow the mother and calf to stay in touch with each other without advertising their presence to potential predators in the area.”

In its place, new mothers communicate to their young through a very quiet, short, grunt-like sound that isn’t audible more than a short distance away.

These sounds, previously unknown to scientists, “can be thought of almost like a human whisper,” says Susan Parks, a professor of biology at Syracuse University, who led the study.

“They allow the mother and calf to stay in touch with each other without advertising their presence to potential predators in the area.”

To collect the acoustic data, the researchers attached small, noninvasive recording tags via suction cups onto North Atlantic right whales in calving grounds off the coasts of Florida and Georgia. They attached tags to juvenile and pregnant whales found in the area and to mother-calf pairs.

“The mothers significantly reduced the number of higher-amplitude, long-distance communication signals they produced compared to the juvenile and pregnant whales,” says Douglas Nowacek, a professor of conservation technology at Duke University.

“They also produced these very quiet, whisper-like sounds. This suggests that right whale mother-calf pairs rely on acoustic crypsis—a type of behavior meant to avoid detection—to reduce the risk of eavesdropping by orcas or sharks lurking in nearby murky waters.”

“Right whales face a number of challenges, including a very low number of calves born in recent years, combined with a number of deaths of reproductive females by collisions with large ships or entanglement in fishing gear,” Parks says.

Scientists estimate that only about 420 North Atlantic right whales exist in the wild today, and there have been 30 confirmed deaths in the past three years, so any additional death is a blow to the species’ odds of survival.

“There are still many things we don’t know about their behaviors, and it is my hope that studies like this will help to improve efforts for their conservation,” she says.

Support for the study came from the US Office of Naval Research and the US Fleet Forces Command, which the Naval Facilities Engineering Command Atlantic manages as part of the US Navy’s Marine Species Monitoring Program.

The research appears in Biology Letters. Additional researchers from the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Center and Syracuse University contributed to the study.

Source: Duke University