October 31 isn’t just Halloween—it also marks a pivotal point in religious history as Reformation Day. And the shared day isn’t just a coincidence.

“The reason he did that was because the next day was All Saints’ Day.”

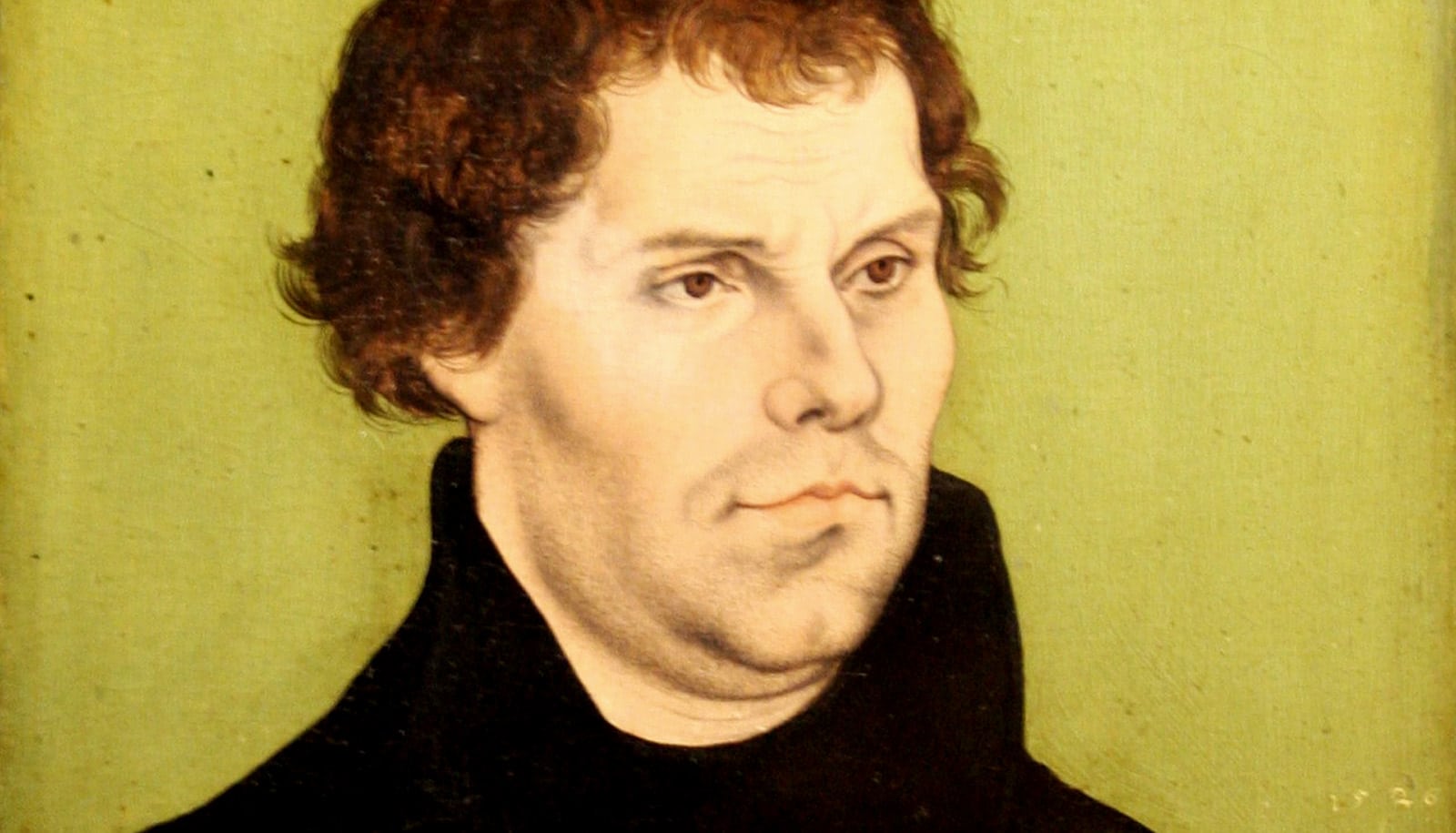

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther, a monk and university professor, released his “Disputation on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences,” also known as “The 95 Theses.” The document, intended as a basis for discussion with church superiors, spoke against the selling of indulgences, a practice that allowed people to “buy” their salvation from local priests.

“I think it’s important that to note Luther wasn’t against indulgences, he just didn’t like the idea of selling indulgences,” says Steven Martinson, professor of German studies and director of the World Literature Program at the University of Arizona. “One had to have a penance for one’s sins, but at the same time, Luther was just outraged that you would have to pay money for that. His emphasis was more on repentance than on penance.”

The distribution of the theses marked the beginning of the Lutheran movement and the eventual spread of Protestantism around the world.

But why on October 31?

“The reason he did that was because the next day was All Saints’ Day,” Martinson says. “He knew that well-educated people were going to come to the services.”

“People would come from all over to see and venerate these relics…”

All Saints’ Day, celebrated on November 1, is dedicated to honoring saints (those who have attained heaven), and one of the ways people did that was through relics. An enviable collection of relics—one from all 5,005 saints—was amassed by Frederick the Wise, Elector of Saxony, who founded the University of Wittenberg, where Luther taught. The relics were housed at the Castle Church, where Luther is said to have nailed his theses to the door.

“The relics were kept very carefully in the church, but on specific occasions, they were publicly shown,” explains Pia Cuneo, professor of art history at the University of Arizona School of Art. “People would come from all over to see and venerate these relics, because according to traditional Christian belief, that made their prayer and their connection to God particularly effective. One of the days on which those relics were shown was All Saints’ Day.”

The showings were important enough that pamphlets full of illustrations and descriptions of the relics often were for sale during public displays. Frederick commissioned Lucas Cranach and his workshop to illustrate the pamphlet, known as the Wittenberg Reliquary Book.

“Luther eventually persuaded Frederick to no longer show these things publicly,” Cuneo says, noting Luther’s personal influence on powerful individuals, as well as the far-reaching effects of his theses, which led to the Protestant Reformation.

So what does all of that have to do with Halloween?

Halloween started as a pagan Celtic festival known as Samhain, which celebrated the harvest and new year. After the Roman Empire conquered the Celts in the first century, festivals traditional to each culture were combined and then eventually usurped by the Roman Catholic Church, which created All Martyrs’ Day in 609 CE.

In 1660, witchcraft was ‘part of everyday life’

Nearly 400 years later, Pope Gregory III replaced All Martyrs’ Day with All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day. All Saints’ Day also was called All-Hallows—and the night before All-Hallows became All-Hallows Eve, the precursor of Halloween.

While people don’t observe Halloween worldwide, many countries have holidays with similar origins. In Mexico and other Latin America countries, October 31 is the start of Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, a three-day celebration to honor deceased loved ones and ancestors. Día de los Muertos also has been historically tied to All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day, giving it a link to the Reformation, too.

Source: Stacy Pigott for University of Arizona