A new book goes back to the 17th century to explore the emergence of both racial slavery and capitalism in American history.

Nearly half of American adults say that it is “very important” for people to educate themselves about the history of racial inequality in the United States, according to a survey by the Pew Research Center last fall. However, the poll revealed a notable division among racial groups, with just over 40% of Asian and White Americans holding this view—compared to just over 50% of Latino/Latinx Americans and 78% of Black Americans.

While recent award-winning works, such as the New York Times’ 1619 Project and Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents, have rigorously recontextualized racial inequality and slavery to illuminate their centrality to American history, large numbers of Americans don’t see learning about these troubling patterns as vital—even though doing so could help us better understand, and therefore address, contemporary challenges.

“The economic system still depends on a profound racial hierarchy,” explains historian Jennifer L. Morgan, chair of New York University’s department of social and cultural analysis. “It still depends on the degradation of Black labor and still depends on and develops tools to segregate and disenfranchise Black people and other working people.”

In her newly released book, Reckoning with Slavery: Gender, Kinship, and Capitalism in the Early Black Atlantic (Duke University Press, 2021), Morgan considers the start of racial slavery and capitalism in America—a crucial moment in world history because, she says, “I think we very much are living in its legacy today.”

Here, Morgan speaks about her new research—including a crucial insight about how statistics helped slavery become “racialized:”

You write that the growth of “numerical literacy” and “faith in the power of statistics” is linked with “hereditary racial slavery.” How so?

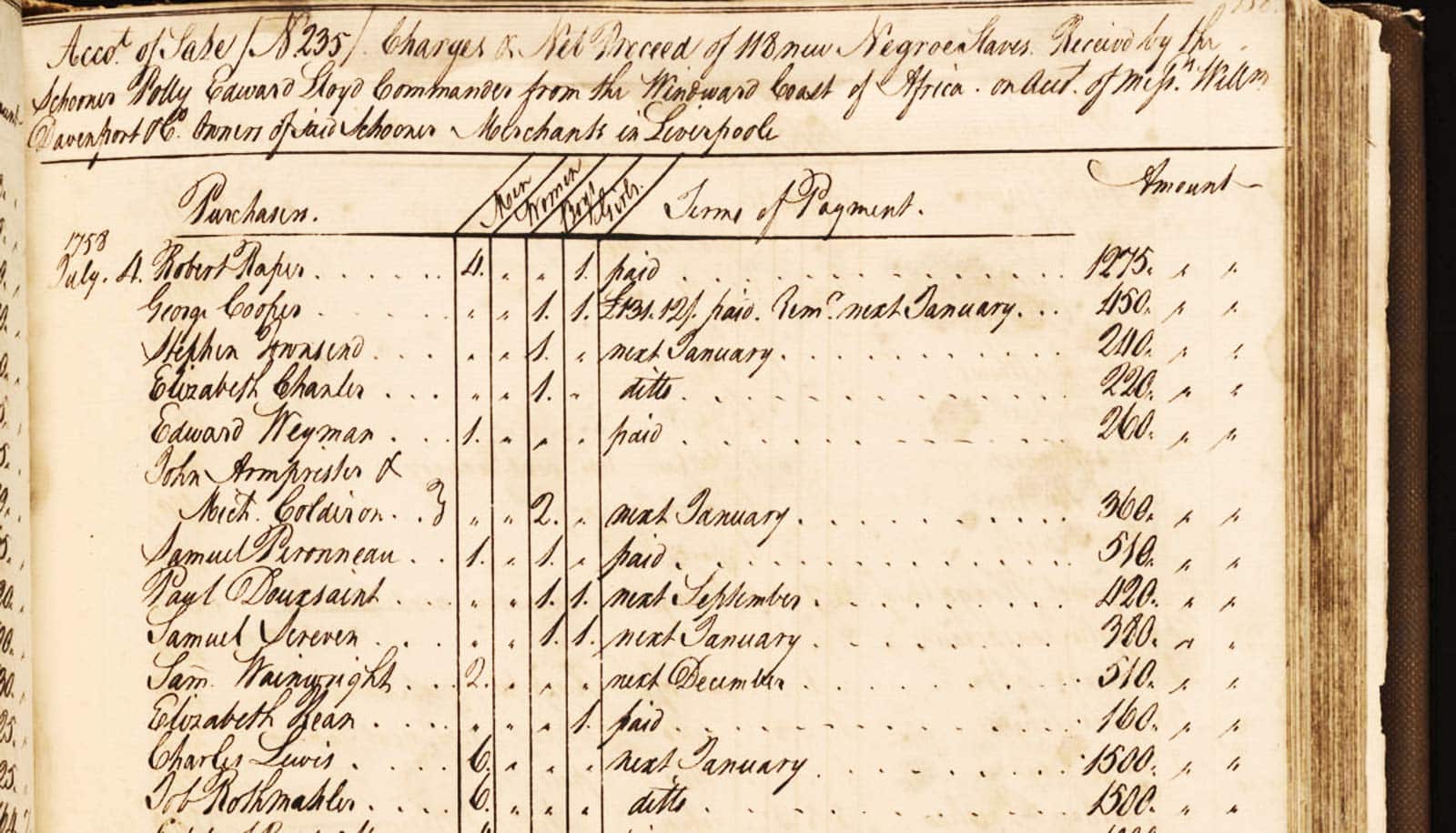

In the history of political economy there is a moment in the 1620s, ’30s, and ’40s where philosophers in England are debating about currency and about value. Later, what others have identified as the first use of demographic data occurs there in 1660.

This is the same moment at which the English have fully committed to the slave trade and the same moment in which England’s first slave economy in Barbados transforms from being an island that’s producing a lot of different crops to being a sugar island, using slave labor.

But those two things are never seen in the same register because of the way our disciplines of history work: the history of the slave trade is separate from political philosophy around numbers and value in England and in the rest of Europe. I started to ask, “What happens if I put those two things in the same frame?”

I would argue that the ways in which enslaved people are turned into commodities depends on this really early and new way of thinking, so the two are inextricable.

But I want to be clear. The slave trade had been going on since the 15th century. Columbus has enslaved Africans on board his ships, so there is no New World without African labor, but it’s mixed. There’s African labor, there’s indentured servitude, there’s the enslavement of Indigenous people. There are a lot of different forms of unfree labor. But there is an association of slavery with Africans and the emergence of an idea of thinking about human beings along categories of race and racial difference and racial hierarchy. This is what I would say happens firmly in the 17th century. And that connection between race and racial hierarchy, and the idea that some people are always going to be enslavable, happens alongside this.

You also observe that “racialized categories of enslavement were not inevitable or hardened.” But such categories surely became foundational. How did a defining aspect of enslavement become “hardened”?

The main intervention that I make in my book, and in my earlier book (Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery, 2004), is to connect the idea of race with reproduction with the experience of enslaved women.

Slavery is a human problem. People are enslaved as a result of wars, as the result of the expansion of territories, as a result of all sorts of things. But what’s new in the slavery that we now know to be racial slavery is that the category of enslavability is passed down. It’s hereditary. It’s seen to be affixed to a whole category of people so that the children of a person who’s enslaved will be enslaved. And the children of the enslaver will always be able to enslave.

And so that idea of hereditary racial slavery is what we think of as the “race/reproduction bind,” as Alys Eve Weinbaum put it in her 2004 book: You can’t think race without thinking reproduction. So if you’re asking how does the category of racial slavery get hardened? I think it gets hardened through the reproductive and the productive work of African women and the ways in which enslavers, English and Spanish and French and Dutch, all understood that those women are giving birth to the institution of slavery.

Enslaved women, as you note, were not only subject to “the slave owner’s power,” but also constituted “the slave owner’s dependence on her productive and reproductive body,” meaning they “embodied both the apex of slavery’s oppressive extractions and its potential undoing.” Readers are surely aware of Harriet Tubman’s courage. How did other, lesser-known women work to undermine slavery?

One of the things that we see early on in the North American colonies is enslaved women trying to use the courts and the church to convey freedom to their children. I talk a little bit about Elizabeth Keye, who’s a woman in Virginia who argued in the courts that she inherited freedom on the basis of being the child of an Englishman and an African woman—even though the Virginia House of Burgesses insisted that children such as herself could only inherit enslavement from their mothers.

What I’ve concluded is that women who give birth to children at a moment at which race is hardening regardless of whether they themselves may be technically free or be in a category of between slavery and freedom can see the process of danger approaching their children. And therefore, you see some women going into the courts to say, “This child is free, this child should be free.”

The book relies on host of methods and disciplines—ranging from anthropology to geography to literature—to illuminate previously unexplored aspects of slavery. Is it possible that a key to understanding contemporary racial issues is taking a more multidisciplinary approach that you use in researching slavery? Do we tend to look at these issues too narrowly?

I think the short answer is yes. We are so embedded in racial hierarchy in this country that I have to believe that it would be helpful in some regard. The layers that you have to dig through in order to actually see what’s going on are very daunting.

You need so many lenses to see all the different ways in which we are still grappling with the legacies of hereditary racial slavery in this country that you can’t just look at it from one perspective. You’re going to miss so many other ways that this is being made manifest.

And so really what I’m saying is that if we look at the history of the early Atlantic world through the eyes of Elizabeth Keye or through the eyes of that unnamed woman on the cover of my book, we understand something. We see the kind of violence that’s embedded in a trade of people. We see what it means that certain people are born into a category of labor.

We see all sorts of ideological maneuvers that slave owners have to go through in order to try to make slavery justifiable.

Sometimes the question “Was racial slavery inevitable” is asked, as if to say, “Well, it didn’t have to happen this way.” I am a historian, and the whole point of the discipline is to understand change over time and see that things aren’t inevitable. That being said, if we don’t get a better sense of how old this institution is and how embedded the transatlantic slave trade is in our contemporary lives—in government, in wealth disparity, in health care, in the experience of violence and dispossession—and in what that produces, we’re not going to clearly find a way out.

Source: NYU