Researchers have used classical concepts to decipher strange quantum behaviors in an ultracold gas.

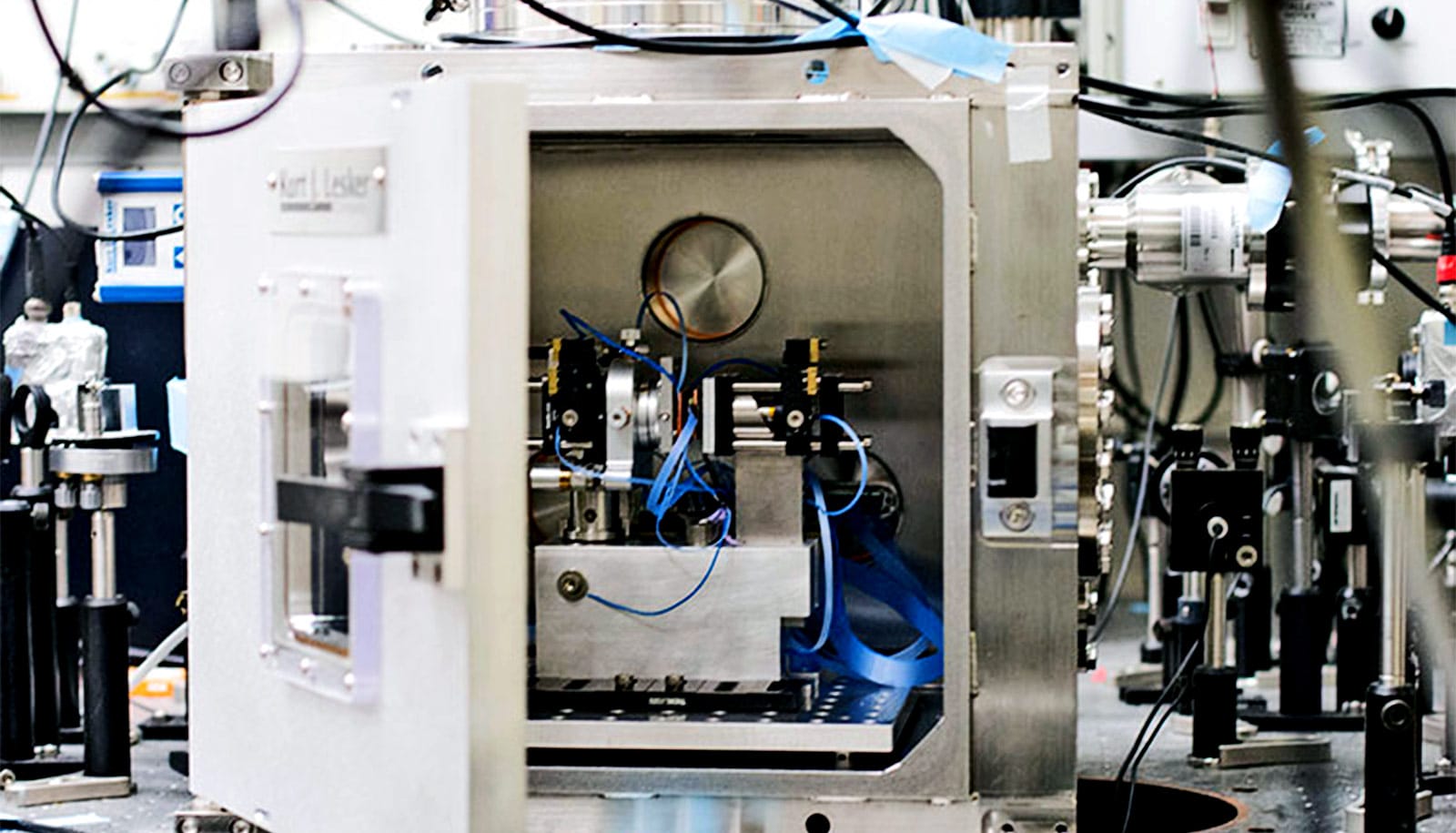

There they were, in all their weird quantum glory: ultracold lithium atoms in the optical trap. Held by lasers in a regular, lattice formation and “driven” by pulses of energy, these atoms were doing crazy things.

“A lot of funny things happen when you shake a quantum system.”

“It was a bit bizarre,” says David Weld, an associate professor who runs a lab in the physics department at the University of California, Santa Barbara. “Atoms would get pumped in one direction. Sometimes they would get pumped in another direction. Sometimes they would tear apart and make these structures that looked like DNA.”

A link between classical and quantum physics?

These new and unexpected behaviors were the results of an experiment the researchers conducted to push the boundaries of our knowledge of the quantum world. The outcomes? New directions in the field of dynamical quantum engineering, and a tantalizing path toward a link between classical and quantum physics.

“A lot of funny things happen when you shake a quantum system,” says Weld, whose lab creates “artificial solids”—low-dimensional lattices of light and ultracold atoms—to simulate the behavior of quantum mechanical particles in more densely packed true solids when subjected to driving forces.

The recent experiments were the latest in a line of reasoning that stretches back to 1929, when physicist and Nobel Laureate Felix Bloch first predicted that within the confines of a periodic quantum structure, a quantum particle under a constant force will oscillate.

“They actually slosh back and forth, which is a consequence of the wave nature of matter,” Weld says. While these position-space Bloch oscillations were predicted almost a century ago, they were directly observed only relatively recently; in fact Weld’s group was the first to see them in 2018, with a method that made these often rapid, infinitesimal sloshings large and slow, and easy to see.

A decade ago, other experiments added a time dependency to the Bloch oscillating system by subjecting it to an additional, periodic force, and found even more intense activity. Researchers discovered oscillations on top of oscillations—super Bloch oscillations.

Then things got weird…

For this study, the researchers took the system another step further, by modifying the space in which these atoms interact.

“We’re actually changing the lattice,” says Weld, by way of varying laser intensities and external magnetic forces that not only added a time dependency but also curved the lattice, creating an inhomogenous force field. Their method of creating large, slow oscillations, he adds, “gave us the opportunity to look at what happens when you have a Bloch oscillating system in an inhomogenous environment.”

This is when things got weird. The atoms shot back and forth, sometimes spreading apart, other times creating patterns in response to the pulses of energy pushing on the lattice in various ways.

“We could follow their progress with numerics if we worked hard at it,” Weld says. “But it was a little bit hard to understand why they do one thing and not the other.”

It was insight from lead author Alec Cao, who is beginning his fourth year at UC Santa Barbara’s College of Creative Studies, that led to a way of deciphering the strange behavior.

“When we investigated the dynamics for all times at once, we just saw a mess because there was no underlying symmetry, making the physics challenging to interpret,” says Cao,.

To draw out the symmetry, the researchers simplified this seemingly chaotic behavior by eliminating a dimension (in this case, time) by utilizing a mathematical technique initially developed to observe classical nonlinear dynamics called a Poincaré section.

“In our experiment, a time interval is set by how we periodically modify the lattice in time,” Cao says. “When we chucked out all the ‘in-between’ times and looked at the behavior once every period, structure and beauty emerged in the shapes of the trajectories because we were properly respecting the symmetry of the physical system.”

Observing the system only at periods based on this time interval yielded something like a stop-motion representation of these atoms’ complicated yet cyclical movements.

“What Alec figured is that these paths—these Poincaré orbits—tell us exactly why in some regimes of driving the atoms get pumped, while in other regimes of driving the atoms spread out and break up the wave function,” Weld adds.

A decades-long quest

One direction the researchers could take from here, he says, is to use this knowledge to engineer quantum systems to have new behaviors through driving, with applications in burgeoning fields such as topological quantum computing.

“But another direction we can take is looking at whether we can study the emergence of quantum chaos as we start to do things like add interactions to a driven system like this,” Weld says.

It’s no small feat. Physicists for decades have been trying to find links between classical and quantum physics—a common math that might explain concepts in one field that seem to have no analog in the other, such as classical chaos, the language for which does not exist in quantum mechanics.

“You’ve probably heard of the butterfly effect—a butterfly flapping its wings in the Caribbean can cause a typhoon somewhere across the world,” says Weld.

“That’s actually a feature of classical chaotic systems, which have a sensitive dependence on initial conditions. That feature is actually very hard to reproduce in quantum systems—it’s puzzling to come up with the same explanation in quantum systems. So this is maybe a small piece of that body of research.”

The research appears in Physical Review Research.

Source: UC Santa Barbara