Researchers can now predict whether an individual will remember or forget based on their neural activity and pupil size.

“As we navigate our lives, we have these periods in which we’re frustrated because we’re not able to bring knowledge to mind, expressing what we know,” says Anthony Wagner, a professor in the social sciences at Stanford University.

“Fortunately, science now has tools that allow us to explain why an individual, from moment to moment, might fail to remember something stored in their memory.”

In addition to investigating why people sometimes remember and other times forget, the team also wanted to understand why some of us seem to have better memory recall than others, and how media multitasking might be a factor.

The research in Nature begins to answer these fundamental questions. The findings may have implications for memory conditions like Alzheimer’s disease and could lead to applications for improving peoples’ attention—and thereby memory—in daily life.

Measuring pupils and brain activity

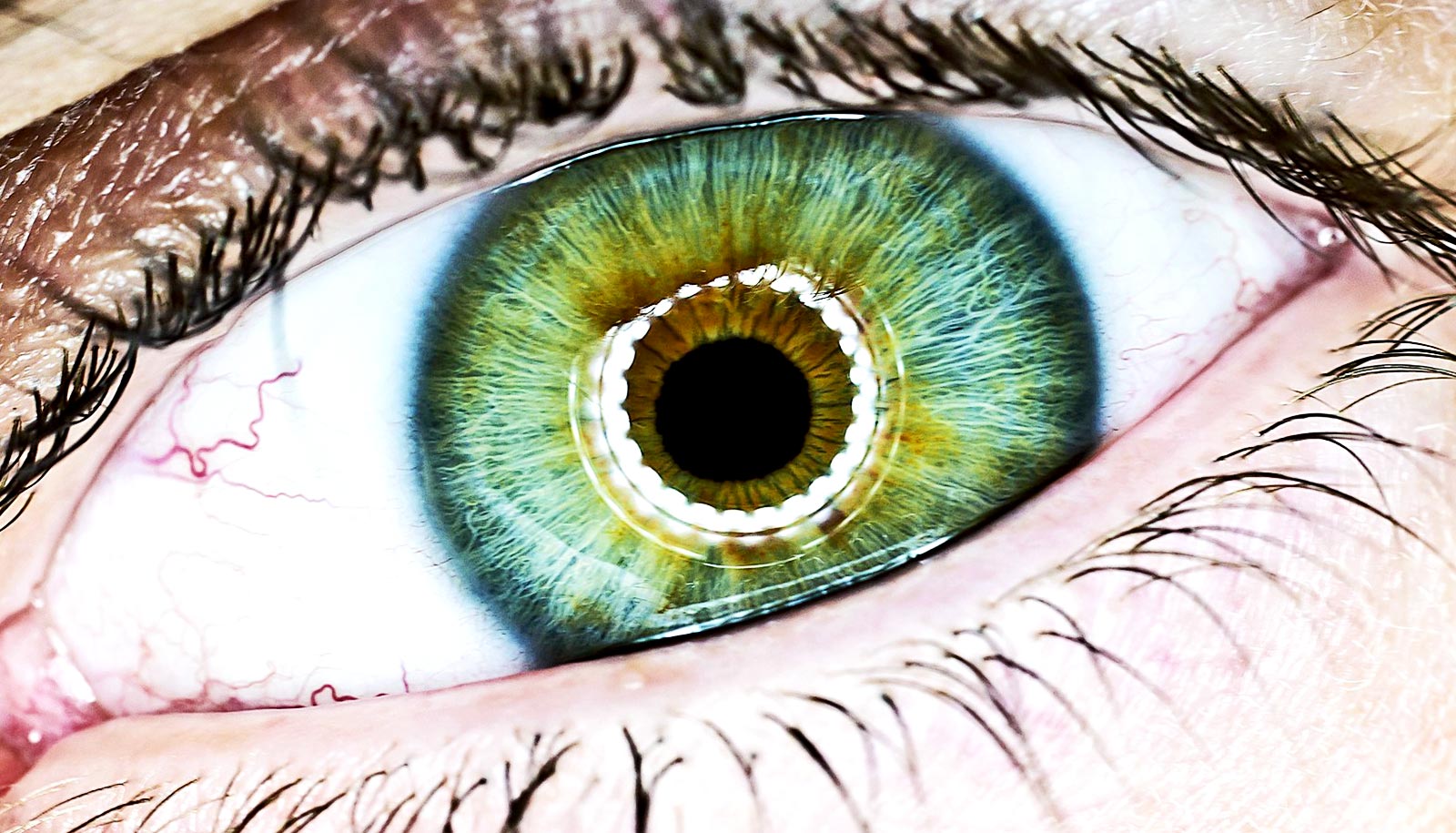

To monitor attention lapses in relation to memory, 80 study subjects between the ages of 18 to 26 had their pupils measured and their brain activity monitored via an electroencephalogram (EEG)—specifically, the brain waves referred to as posterior alpha power—while performing tasks like recalling or identifying changes to previously studied items.

“Increases in alpha power in the back of your skull have been related to attention lapses, mind wandering, distractibility, and so forth,” says lead author Kevin Madore, a postdoctoral fellow in the Stanford Memory Lab. “We also know that constrictions in pupil diameter—in particular before you do different tasks—are related to failures of performance like slower reaction times and more mind wandering.”

Researchers also studied differences in people’s ability to sustain attention by examining how well subjects were able to identify a gradual change in an image, while they assessed media multitasking by having individuals report how well they could engage with multiple media sources, like texting and watching television, within a given hour. The scientists then compared memory performance between individuals and found that those with lower sustained attention ability and heavier media multitaskers both performed worse on memory tasks.

Wagner and Madore emphasize that their work demonstrates a correlation, not causation. “We can’t say that heavier media multitasking causes difficulties with sustained attention and memory failures,” says Madore, “though we are increasingly learning more about the directions of the interactions.”

Memory, learning, and attention

According to Wagner, one direction that the field as a whole has been heading in is a focus on what happens before learning or, as in this case, before remembering even occurs. That’s because memory heavily depends on goal-directed cognition—we essentially need to be ready to remember, have attention engaged and a memory goal in mind—in order to retrieve our memories.

“While it’s logical that attention is important for learning and for remembering, an important point here is that the things that happen even before you begin remembering are going to affect whether or not you can actually reactivate a memory that is relevant to your current goal,” says Wagner.

Some of the factors that influence memory preparedness are already within our control, he says, and can therefore be harnessed to assist recall. For example, conscious awareness of attentiveness, readiness to remember, and limiting potential distractions allow individuals to influence their mindsets and alter their surroundings to improve their memory performance.

While these relatively straightforward strategies can be applied now, the researchers note that there may eventually be targeted attention-training exercises or interventions that people can use to help them stay engaged. These are referred to as “closed-loop interventions” and are an active area of research.

As an example, Wagner and Madore envision wearable eye sensors that detect lapses in attention in real-time based on pupil size. If the individual wearer can then be cued to reorient their attention to the task at hand, the sensors may assist learning or information recall.

Finally, advances in measuring attentional states and their effects on the use of goals to guide remembering also hold promise for a better understanding of disease or health conditions that affect memory.

“We have an opportunity now,” Wagner says, “to explore and understand how interactions between the brain’s networks that support attention, the use of goals and memory relate to individual differences in memory in older adults both independent of, and in relation to, Alzheimer’s disease.”

Additional coauthors of the study are from Stanford and UC San Francisco. The National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Aging supported the work.

Source: Stanford University