A Late Cretaceous reptile evolved to have resilient tooth enamel similar to that in mammals, Priosphenodon specimens from Argentina show.

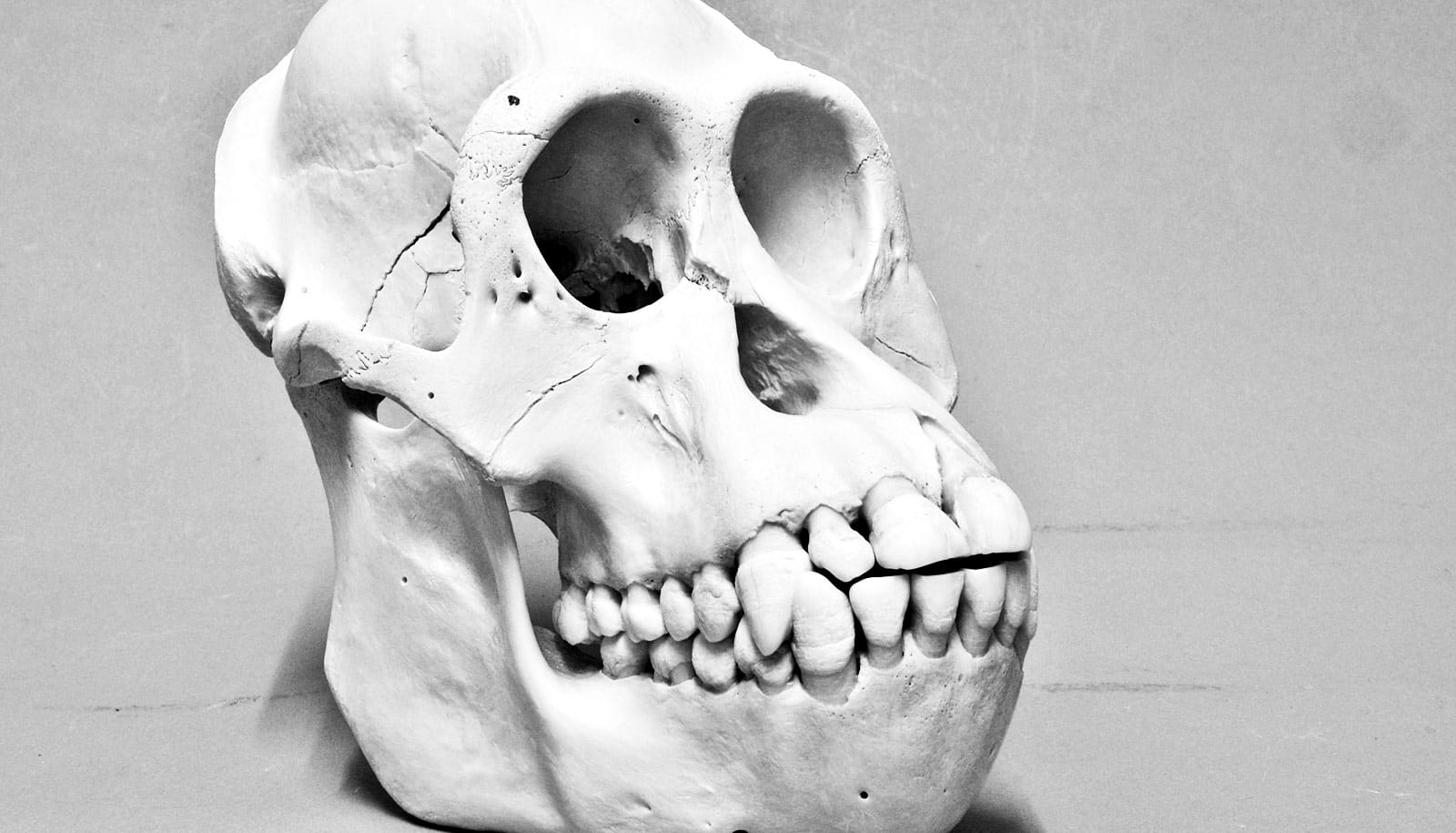

Priosphenodon was a herbivore from the Late Cretaceous period that was about one meter long. Part of a group of reptiles called sphenodontians, these reptiles are unique in that they lost their ability to replace individual teeth. Instead, sphenodontians added new teeth to the back ends of their jaws as they grew.

“Priosphenodon has the strangest teeth I have personally ever seen,” says Aaron LeBlanc, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of biological sciences at the University of Alberta and lead author of the study. “Some aspects of their dental anatomy are reminiscent of what happened in the evolution of early mammal teeth.”

In order to look more closely at the teeth of Priosphenodon, the researchers cut open pieces of jaw and examined tissue-level detail preserved inside the teeth. They also used non-invasive CT scans to examine more complete jaw specimens.

“Priosphenodon enamel is not only thicker than that of most other reptiles, the enamel crystals are ‘woven’ into long threads that run through the whole width of the enamel. These threads are called enamel prisms, and they are almost exclusively found in mammals,” says LeBlanc.

“Our results suggest that strong selective pressures can force reptiles to come up with some very innovative solutions to the problems associated with tooth wear and abrasive diets—some of which mirror what happened in our earliest mammal ancestors.”

Hans Larsson, director of McGill University’s Repath Museum, is also an author of the new study in Current Biology.

“It’s extraordinary how evolution can find solutions to tweak even the microstructure of tooth enamel and reorganize the development of teeth in these bizarre reptiles,” says Larsson, research chair in vertebrate paleontology.

The scientists also note that there is one kind of lizard alive today that has prismatic enamel like Priosphenodon—the spiny-tailed lizard of Australia. Like Priosphenodon, it mostly eats plants and has lost the ability to replace its worn teeth. However, the two reptiles are not closely related.

The specimens were found in Argentina’s Río Negro province as part of ongoing collaborative fieldwork and research between Michael Caldwell of the University of Alberta and Argentinian paleontologist and fieldwork leader Sebastián Apesteguía.

Funding for the study came from Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica in Argentina, National Geographic, and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Source: McGill University