There is a way to counter the assumption that women are less electable than men, report researchers.

In a primary election, if voters believe that it is too hard or impossible for a woman candidate to win a general election, they’ll support a male candidate from their party instead—even if they personally preferred a woman, according to the research.

The findings appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

When voters encounter evidence showing that women political candidates garner just as much support as men do in US general elections, voters’ intentions to support women presidential candidates increased by about 3 percentage points, the researchers’ data show.

“While the effects of our short intervention were small, primary elections are often decided by just a few percentage points,” says Robb Willer, senior author of the paper and a professor of sociology in Stanford University’s School of Humanities and Sciences.

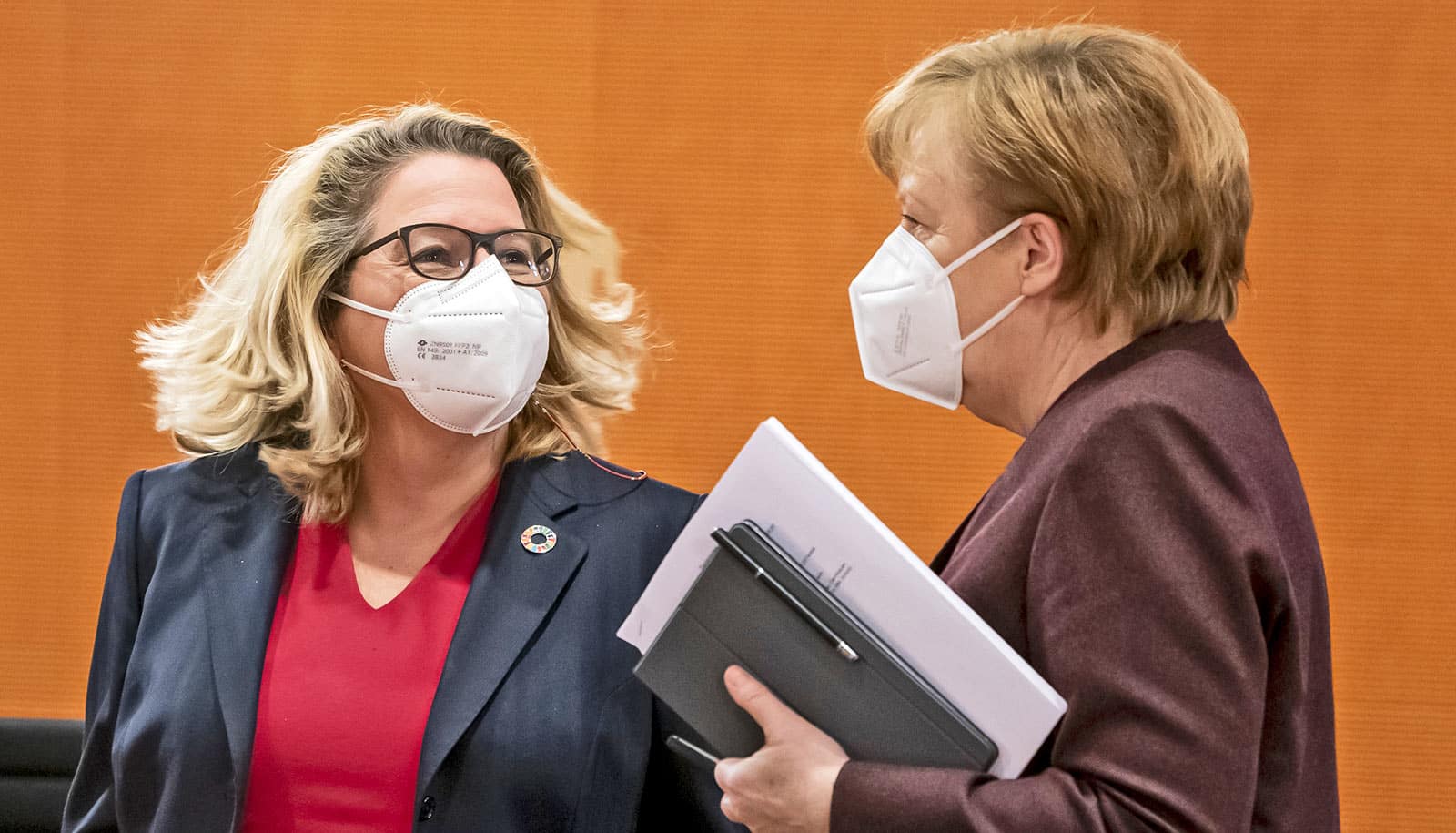

With 2022 primary elections nearing and many women getting ready to run for prominent positions in government, the scholars’ findings are particularly applicable, since it is where voters are most concerned with whether candidates can win, Willer says.

To better understand voters’ perceptions of electability and how it may undermine women candidates at the ballot box, the researchers collaborated with the women’s leadership organization LeanIn.org to field a survey during the 2020 Democratic presidential primary election.

Warren, Harris, Klobuchar, and Gillibrand

The Democratic primaries provided a unique opportunity for academic study: Never before in a US presidential election were there multiple, competitive candidates who were women, says Christianne Corbett, a PhD candidate in sociology and one of the co-lead authors of the paper.

Assumptions about group behavior can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“In most prior US presidential primaries, all the candidates have been men. When there have been competitive women candidates, there has only been one, so it’s been very difficult to disentangle gender from all the other characteristics that specific candidates have,” Corbett says.

Since there were multiple women candidates to study—Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, and Kirsten Gillibrand—the researchers were better able to assess the impact of gender bias and what drove voters’ stereotyped presumptions.

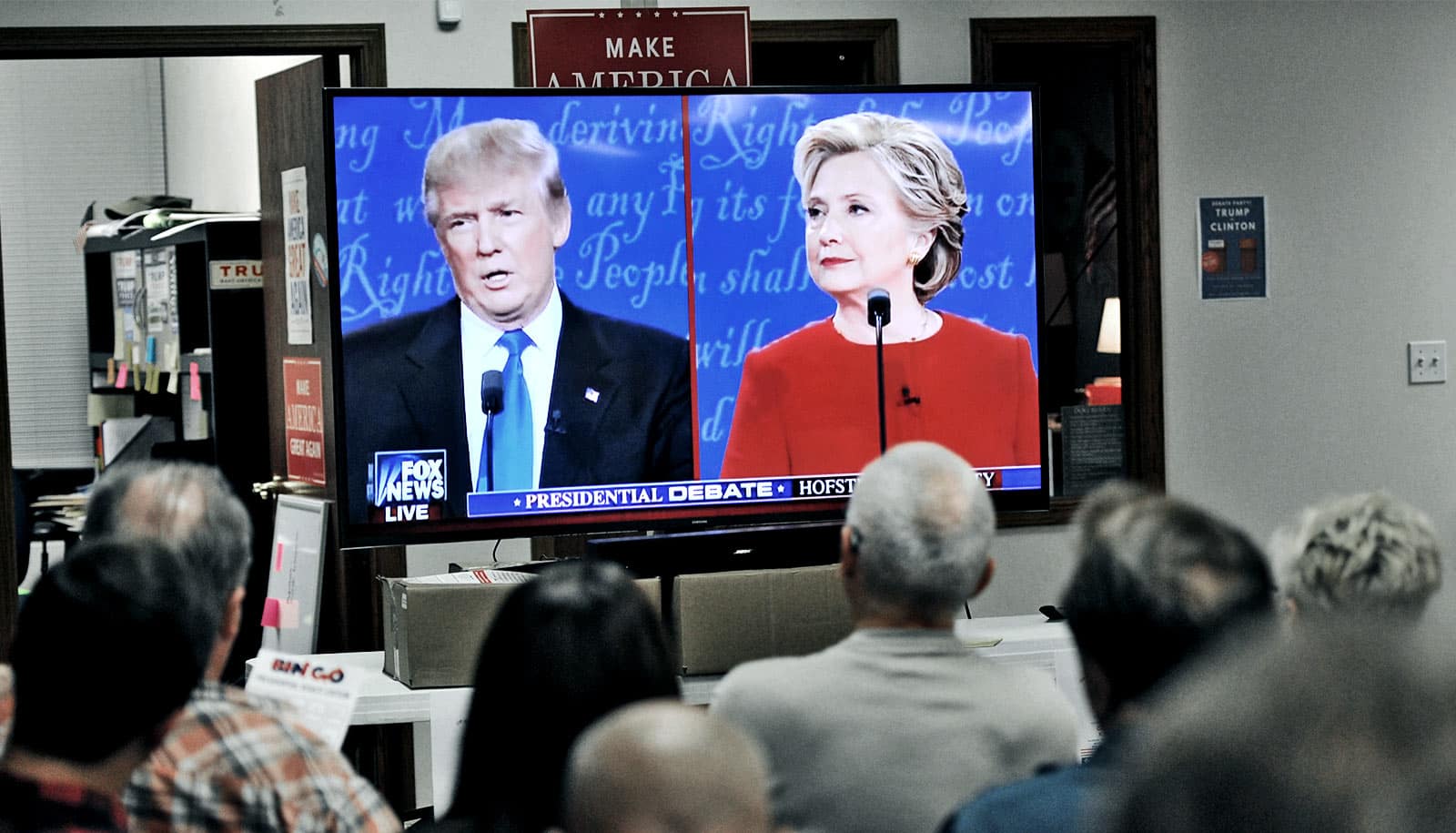

In a survey administered to a sample of nearly 1,000 likely Democratic primary voters, the researchers asked a series of questions like “Do you think it will be harder or easier for a woman to win the 2020 election against President Trump, compared to a man?” and “If he/she were guaranteed to win, who would you most want to be the next president?” and provided 12 choices that included all the leading candidates at the time of the survey.

They found that overall, 76% of the surveyed respondents thought that it would be harder for a woman to beat then-president Donald Trump in the general election.

‘Pragmatic bias’

Some of the reasons voters cited for perceiving a woman candidate as less electable included the idea that Americans were not yet ready to elect a woman president and that gender biases in society would hurt her campaign—like being held to a higher standard than a man, dealing with biased media coverage and facing harsher or more effective attacks by the opposition. In sum, many Democratic voters didn’t see it as practical for a woman to run if they wanted their party to win the election.

Moreover, the scholars also saw a clear pattern of voters who, while they may have personally preferred a woman candidate as their party nominee, nonetheless switched their voting intentions towards a male candidate when they perceived the woman candidate to be less electable.

Social scientists have long documented the personal biases women political leaders face. Here, the scholars identified another, subtler barrier: “pragmatic bias.” Pragmatic bias is different from personal bias in that it is based in part on what other people may think about a particular group and the barrier this may present to members of that group.

The authors argue that pragmatic bias is not just limited to gender and can extend to other characteristics, like race.

An example of pragmatic bias surfaced in the 2008 primaries when Barack Obama ran for US president. At the time, many speculated—including Michelle Obama—whether the United States was ready to elect a Black man as their president.

“This was part of why the Obama campaign centered the idea of “yes, we can” in 2008. They wanted to convince Democratic party primary voters that a Black man could win the presidential election,” Willer says.

These assumptions run the risk of turning into what the scholars have called an “electability trap.” Assumptions about group behavior can become a self-fulfilling prophecy: If voters won’t support a candidate because they believe other Americans will not support the candidate, they have the power to make their assumption true and the candidate won’t win.

“One aspect of pragmatic bias that is especially pernicious is that people who themselves do not hold gender biases—and perhaps are even actively trying to further the advancement of women—might still act against women because of what they see around them. They may see that women candidates still contend with gender bias and conclude that a woman will not win and decide to vote for a man instead,” says Corbett.

How to counter the bias

While women are still greatly underrepresented in politics, academic research has found that in general elections, and US Congressional races in particular, women candidates receive approximately the same level of support as men. The researchers wanted to know whether interventions might be implemented that would mitigate bias among voters and help them overcome their assumptions about electability.

In one experiment with likely Democratic primary voters, they found that simply reporting the percent of Americans reporting they are ready for a woman president was not persuasive enough.

What did sway people’s intentions to vote for a woman candidate, however, was providing solid evidence, rooted in the academic literature, showing that women and men candidates are equally electable. Participants were given a short, 300-word summary describing how research shows voters are as likely to vote for a woman candidate as they are a man in US general elections. (In the control group, participants were given a generic essay about the 2020 election).

Providing behavioral evidence proved key to making the intervention effective, says paper co-lead author and sociology PhD student Jan Voelkel. “It might be more persuasive to tell people what others are actually doing rather than what others are thinking,” he says. Voters must not only believe that a majority of other voters want to see a woman candidate win, they also need to believe that a majority of voters will show up to the polls and vote for her, Voelkel emphasizes.

In addition, Willer also speculates that countering perceptions are likely better received by voters if it comes from another source besides the candidate herself.

The researchers see pragmatic bias as thwarting social progress and perpetuating existing inequalities that many are trying to overcome.

“People base their sense of what is possible on what they have seen happen in the past. Often this makes a lot of sense, but it can also be an overly conservative force, slowing social changes that most people would like,” Willer says.

“In order for women to achieve equal access to political leadership, it is important for voters to update their sense of what is possible for women running for office. Until they do, women will face this extra barrier,” he adds.

Also contributing to the paper was Marianne Cooper, a senior research scholar at Stanford’s VMware Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab.

This research had support from the VMWare Women’s Leadership Innovation Lab and funding from the Stanford Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society. Data from the first study presented in the PNAS paper were collected in collaboration with LeanIn.org.

Source: Stanford University