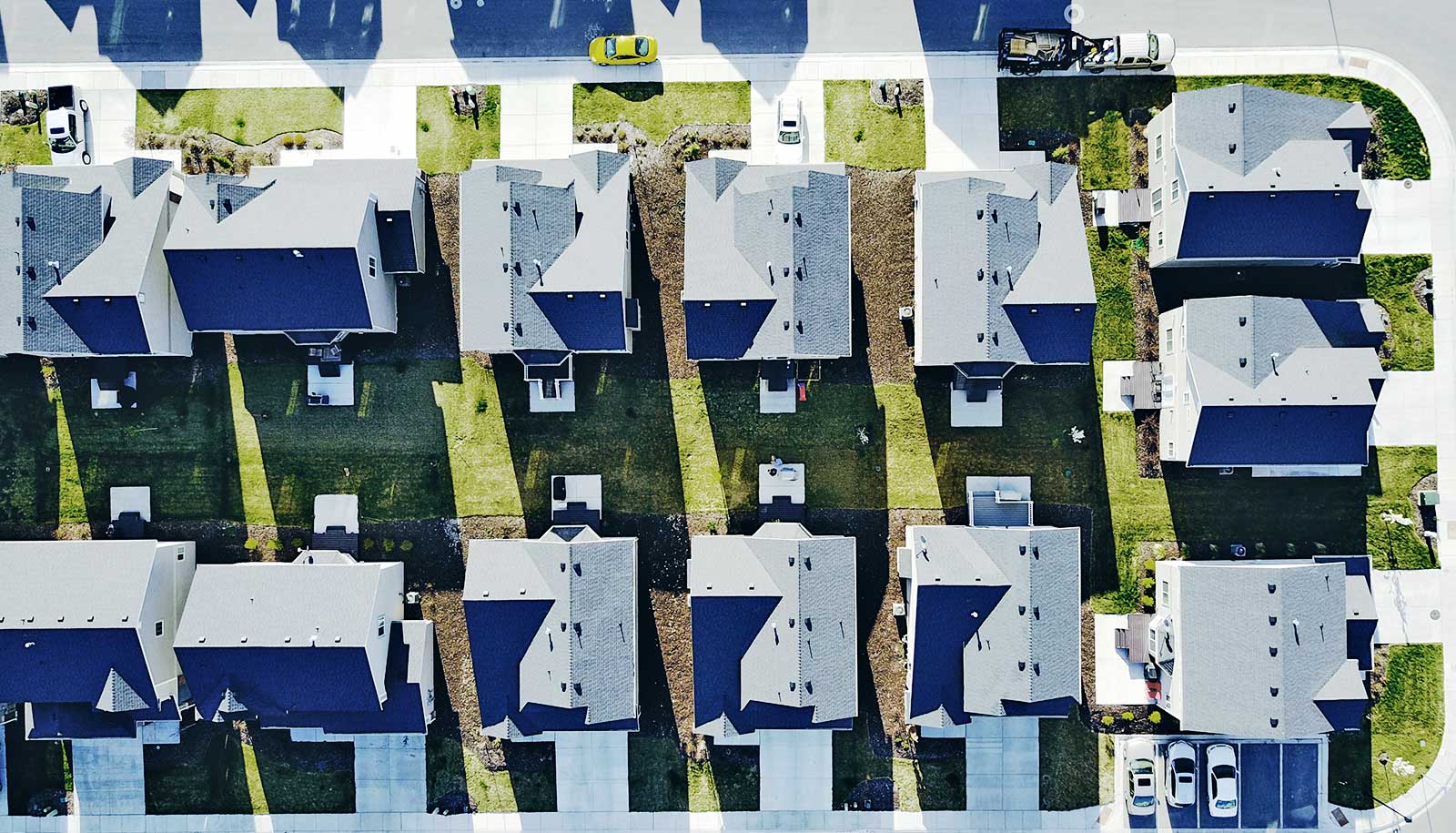

A new book depicts poverty’s move to American suburbs, explains how this shift occurred over the last 25 years, and discusses how public policy must be geared toward helping people in poverty in the suburbs without neglecting the urban poor.

Scott W. Allard is a professor in the Evans School of Public Policy & Governance at the University of Washington. In his new book, Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty (Russell Sage Foundation, 2017), Allard discusses the modern reality of American poverty and how it has changed.

https://www.facebook.com/uwnews/videos/1537113266381263/

One reviewer writes that, in addition to “innovative economic analysis,” the book also “represents a deeply moral call to update our thinking about vulnerable people across America and rethink outdated assumptions about how to assist them.”

Here, Allard answers a few questions about his work:

How did you come to write this book?

Just before the Great Recession, I was finishing the initial manuscript for my first book, Out of Reach: Place, Poverty, and the New American Welfare State (Yale University Press, 2008), which was about the spatial mismatches between the location of poverty in cities and the social service organizations that provide help to the poor.

While writing, I visited a food pantry outside of Los Angeles that had reported large caseload increases in the previous years. Driving to the interview, I found myself entering a fairly exclusive suburban area. I wondered if I had the wrong address, but continued on and found the pantry’s executive director waiting for me near the front door. We talked about how caseloads had increased by at least 10 percent each month for the previous year. This was clearly a community in need. I found similar examples in other parts of the same suburban region. As an urban poverty researcher, I found myself puzzling over what to make of these findings.

Around this time, I began participating in conversations at the Brookings Institution Metropolitan Policy Program, where I am a nonresident senior fellow, about shifts in the geography of poverty within metro areas. A report by my colleagues Alan Berube and Elizabeth Kneebone at Brookings documented that the suburban poor outnumbered the urban poor for the first time in modern history. Although some of this increase was due to the sluggish economy of the early 2000s, it was clear that a major demographic change had occurred, with relatively little notice, right under our noses.

With Brookings’ support, I coauthored a report in 2010 titled “Strained Suburbs: The Social Service Challenges of Rising Suburban Poverty,” which drew on interviews with about 100 suburban nonprofits. The report highlighted numerous challenges for suburban safety nets, particularly the lack of program funding and the political obstacles to responding to rising poverty.

The book project expands on this 2010 Brookings report by developing a larger argument about the intersectionality of place, poverty and race in the US today. In addition to a deeper examination of poverty trends across cities and suburbs, Places in Need also provides a more thorough examination of how public assistance and social service programs have responded to the changing geography of poverty.

Would you briefly describe your methods?

This book draws on a number of different types of data to tell a complete story about the changing geography of poverty and its consequences for the safety net. The narrative tells a national story, but also drills down into the experiences of three metro areas: Chicago, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC.

The first section of the book examines changes in poverty across cities and suburbs using census tract data from 1990 to 2014. The second half analyzes administrative data from key safety net programs and in-depth interviews with roughly 100 suburban human service executives to highlight which portions of the safety net respond well to the shifting geography of poverty documented at the start of the book. Throughout, I use examples from the three metro study sites to provide texture to the argument and analysis.

You write that the rise of suburban poverty should not only challenge the popular discourse around place and poverty, but also change how poverty research is conducted. How do you feel poverty research needs to change?

Questions about poverty and inequality being posed in urban contexts remain critical, but alongside these lines of inquiry should be a set of new questions that focus on poverty problems in suburbs and across metropolitan regions. For example, existing research underscores the impact of living in high-poverty isolated urban and rural communities, but more mixed-methods research should explore issues of segregation, exclusion, and isolation among the suburban poor.

The 2016 presidential campaign brought references to high poverty in America’s inner cities. What are the dangers of viewing poverty as a mainly urban phenomenon?

We can trace the links between poverty and urban settings back to the War on Poverty, where national debate explicitly connected poverty to urban places. Popular understandings that poverty is an urban problem in the 50 years that followed has shaped our perceptions of how we should address poverty problems.

Rhetoric in the recent presidential campaign only further reinforced these misperceptions. Not only do we expect poverty to be located in cities, but we also expect that much of our public and private capacity to provide assistance to the poor should be located in cities. Misconceptions that poverty is an urban problem lowers expectations that suburban communities should commit resources to the fight against poverty.

You write of the “othering” of poverty. Would you explain a bit what that is?

When society links poverty to cities, it also often implicitly or explicitly links poverty to race and ethnic minorities living in cities.

Beliefs that poverty is experienced mostly by urban black and Hispanic residents powerfully influence how society thinks about antipoverty solutions by defining who is “deserving” and who is not. Such attitudes directly translate into lower support for more generous or accessible antipoverty assistance, and greater support for more punitive policies.

The spatial discourse around poverty, as I call it, may tie into competitive assessments by whites about public and private resource allocation between a deserving “us” versus an undeserving “them.”

In the end, Places in Need argues that the familiar discourse around race, place, and poverty undermines support for the antipoverty safety net by distancing certain types of communities from responsibility to address need and by anchoring policy debate to racial stereotypes.

You say also that federal budget proposals and health care legislation now being considered in Congress “will undermine some of the most critical, responsive parts of the safety net.” Would you elaborate?

Current budget proposals from Congress seek funding cuts for most federal antipoverty programs and block grant conversions for others. Of particular concern are proposed cuts to the Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program, or SNAP, and Medicaid, which help millions of Americans and do so fairly consistently across different types of geographic locations.

Cuts to the safety net currently under debate in Washington, DC, would lead to millions of Americans falling into poverty and would reverse the economic gains many low-income households have made following the Great Recession. Moreover, these cuts would hamper the ability of programs to be responsive to increases in poverty that may occur during the next economic downturn.

What measures do you suggest from government and social services to help reduce suburban poverty?

First, it is critical to maintain federal commitments to anti-poverty programs like food stamps (now called SNAP) or the Earned Income Tax Credit, which have been proven effective at reducing poverty. Increasing federal funds for social service programs targeted in underserved areas is critical as well.

It also is important to find ways to cultivate a new generation of local leaders and nonprofit organizations capable of tackling poverty challenges in suburbs. Government and philanthropy must find pathways to building collaborations between suburbs and cities that begin to scale up regional solutions to the needs of low-income Americans. Ultimately, suburbs and cities have a shared interest in addressing poverty in all places.

You do note a few positive post-Great Recession economic trends, yet you believe the changing geography of poverty will persist. Why is this?

There has been some very good economic news in the last year—unemployment remains at very low levels, employment has returned to pre-Great Recession levels, and poverty has finally begun to fall.

But there are signs of caution as we approach the end of the current recovery. The number of persons in poverty in metropolitan America remains well above pre-recession levels. Many working-age adults remain out of the labor force, and the percentage of the population with a job still remains well below pre-recession levels as a result. The labor force participation and unemployment rates for adults with a high school degree or less still have not returned to pre-recession levels. Levels of income inequality remain unchanged. There continue to be too few good-paying jobs that do not require advanced education or training than in past decades.

What can people do individually to help ease suburban poverty?

In addition to supporting public policies and elected leaders committed to a strong safety net that can help families in times of need, we must strengthen our private commitments to charity and nonprofits that provide critical help to low-income households. When I speak about the book, I encourage people to look for a local nonprofit and make a new donation or find time to volunteer. There’s lots we can do in our communities to make a difference.

What is next in your work?

Right now, I am working on several projects examining food insecurity and hunger in America. We need to better understand why food insecurity has increased and how we can find solutions to improve food outcomes. I’m also leading a national network of scholars exploring emerging issues of place and poverty in the US. Finally, I am starting a number of projects that use administrative data to generate insight into how we can craft safety net programs to better serve families and children.

My hope is this continued research will yield new insights into policies and programs that can best reduce poverty and help low-income families grab the next rung on the ladder.

Source: University of Washington