There are immediate, concrete steps governments can take to address enduring problems in law enforcement, says law professor Barry Friedman.

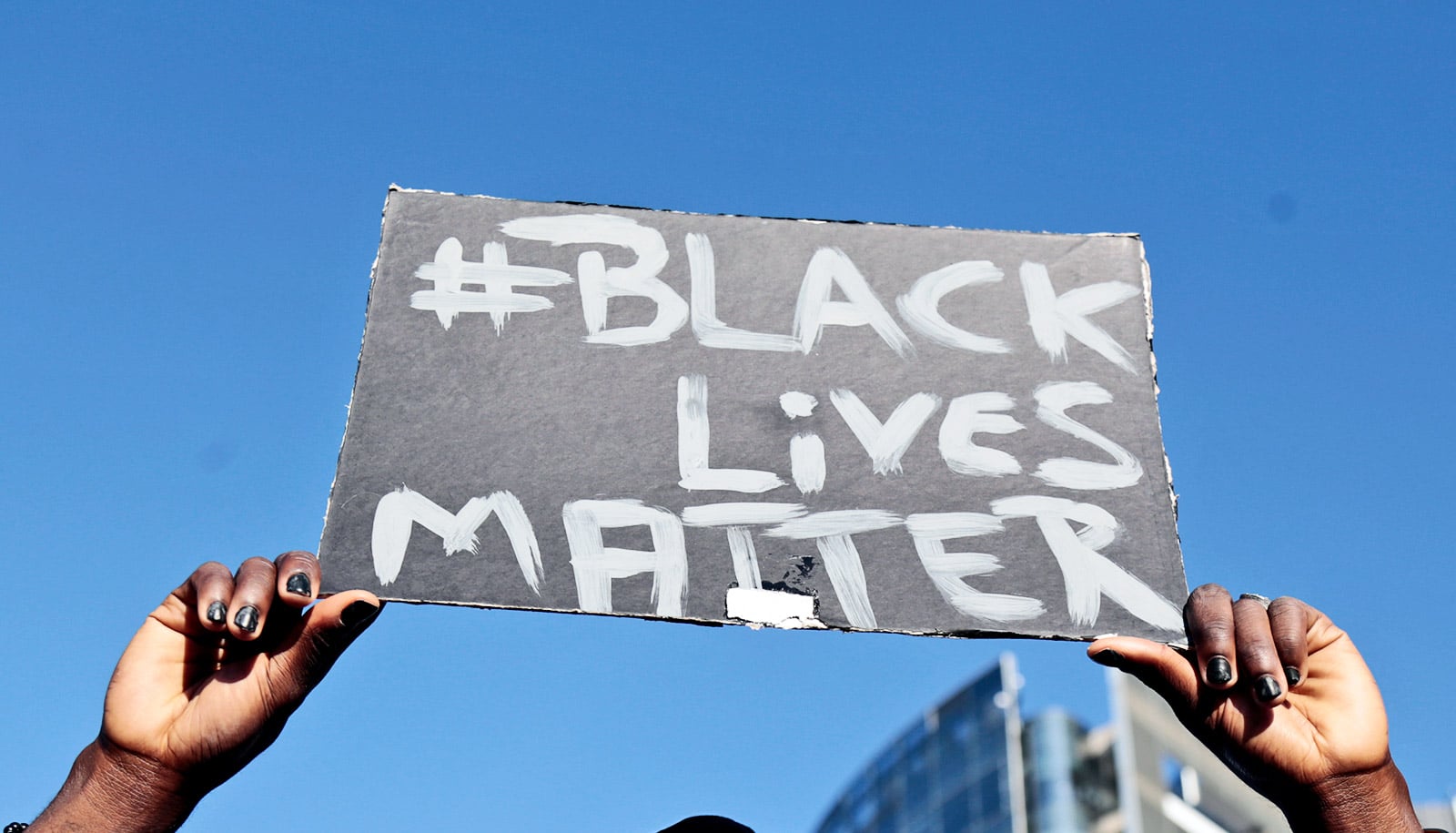

In the weeks following the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, protests erupted nationwide with people demanding justice for Floyd and condemning a policing system in which police kill Black people at disproportionately higher rates than white people. Marches often became chaotic scenes with law enforcement tear-gassing protestors and firing rubber bullets into crowds.

During these weeks of unrest, officers from departments across the country made national news when video showed them shoving and beating protestors. In New York, these images followed reports relating to the COVID-19 pandemic that highlighted the NYPD arresting greater numbers of Black people for social distancing violations in a manner reminiscent of New York City’s former stop-and-frisk policies.

Collectively, these accounts of misconduct and discriminatory treatment highlight long-standing inequities in the US criminal justice system that have prompted a national reckoning and a call for widespread police reform.

New York University law professor Barry Friedman, author of Unwarranted: Policing Without Permission (Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2018), is among those advancing models of reforms. Friedman is a co-founder and faculty director of New York University School of Law’s Policing Project, an organization that partners with communities and police departments to promote public safety through transparency, equity, and democratic engagement.

New York State Attorney General Letitia James recently appointed James to aid in her investigation of the NYPD’s response to protests in late May and June. He also joined a coalition of law school faculty in releasing a report that outlines “immediate, concrete steps federal, state, and local governments can take to address enduring problems in policing.”

Here, Friedman discusses systemic inequality in the law enforcement system, the future of reform, and the state of community-police relations in the aftermath of Floyd’s murder:

George Floyd’s death has renewed national conversations on police violence, particularly directed at Black people and other people of color. How can this violence be prevented and what needs to happen for officers to be held accountable when it does?

The data is clear that policing in this country has a disproportionate impact on Black people, and that needs to be addressed lest we continue to perpetuate a history of systematic racism. The core focus of the Policing Project is on what we call “front-end accountability,” which means that we have to put in place systems to avoid these outcomes before they occur. Legislative bodies have been remiss—largely ignoring the failings of policing. Together with Policing Project co-founder Maria Ponomarenko and a coalition of law school faculty from across the country, I generated a list of urgently needed reforms to address these enduring problems in American policing.

In particular, reforming police use of force is an utmost priority. While Changing the Law to Change Policing includes legislative fixes such as national use-of-force standards and state-level minimum policy requirements, police departments can and should take it upon themselves to review and improve immediately their current use-of-force policies. Last year, the Policing Project partnered with the Camden County Police Department to generate an innovative use-of-force policy that goes well beyond the Supreme Court’s minimal constitutional principles regarding use of force, to state clearly that officers must do everything possible to respect and preserve the sanctity of all human life, avoid unnecessary uses of force, and to minimize the force that is used, while still protecting themselves and the public. This policy has been held up as a national model and received significant attention in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd.

Most calls for police reform are centering on the concept of “defunding” or “re-imagining” law enforcement. How is the Policing Project addressing those efforts?

This country sends officers to deal with too many social problems—substance abuse, mental illness, homelessness, domestic disputes—for which they are not properly trained or equipped. Not only does a police response fail to address these problems effectively, it also leads to over-criminalization and further strains relationships between communities and the police who are meant to serve them.

One of our highest priorities at the Policing Project is re-imagining how we achieve public safety in our communities. True public safety must address social problems that traditional law enforcement, acting alone, cannot. We are researching and developing a new model for first responders—based on the model of emergency room doctors—in which responders are generalist professionals trained to diagnose, stabilize, and resolve situations as best they can, and call in specialists if needed. Their range of skills would be broad and geared towards stabilization and improved outcomes. And most importantly, their oath, as for doctors, would be “first, do no harm.”

We are also drafting a framework for jurisdictions, advocates, and police agencies, and we are currently pulling together national convenings of communities, advocates, policymakers, academics, and policing agencies to chart a course for re-imagined public safety and first response. We take an “all stakeholders” approach in which we endeavor to have all voices at the table, including folks who do not always talk—such as activists and the police themselves.

Community engagement typically is touted as essential for building relationships between communities and the police that serve them. In today’s fraught environment, where distrust seems to be at an all-time high, is that even feasible?

The national calls to defund or abolish policing are a function of how badly communities feel police have failed them. It is imperative, now more than ever, that communities not only have a meaningful seat at the table, but are considered leaders in redesigning policing and first response. We call this democratic policing—that the people have a voice in how they are policed.

The Policing Project is committed to advancing the concept of democratic accountability. There is currently little accountability at all, and what does exist usually occurs at the back end—after something has gone wrong or someone has been harmed. By creating accountability structures on the front end, we ensure that people have a meaningful say in how they are policed, and that enforcement strategies and priorities reflect the will of the community, and contemplate their experiences and perspectives.

Some police reform likely will come through federal, state, and local legislation. But departments also must proactively re-imagine their role in achieving public safety. Community engagement, particularly through democratic accountability, is indispensable in this moment.

Source: NYU