Researchers have found a way to make plastic waste suck up excess carbon dioxide.

The newly discovered chemical technique seems like a win-win for a pair of pressing environmental problems.

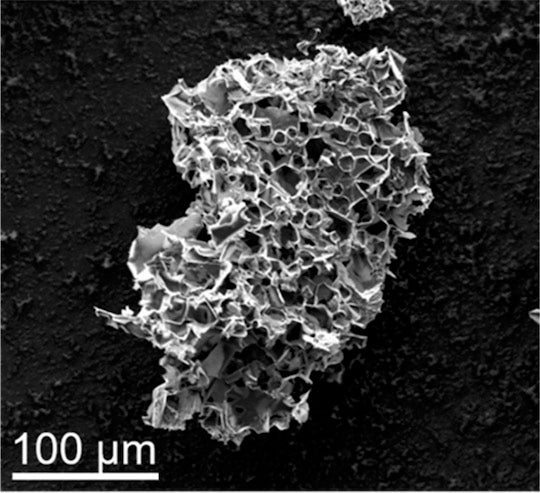

In the journal ACS Nano, researchers report that heating plastic waste in the presence of potassium acetate produces particles with nanometer-scale pores that trap carbon dioxide molecules.

These particles can be used to remove CO2 from flue gas streams, the researchers say.

“Point sources of CO2 emissions like power plant exhaust stacks can be fitted with this waste-plastic-derived material to remove enormous amounts of CO2 that would normally fill the atmosphere,” says James Tour, professor of chemistry and of materials science and nanoengineering at Rice University. “It is a great way to have one problem, plastic waste, address another problem, CO2 emissions.”

A current process to pyrolyze plastic known as chemical recycling produces oils, gases, and waxes, but the carbon byproduct is nearly useless, Tour says. However, pyrolyzing plastic in the presence of potassium acetate produces porous particles able to hold up to 18% of their own weight in CO2 at room temperature.

In addition, while typical chemical recycling doesn’t work for polymer wastes with low fixed carbon content in order to generate CO2 sorbent, including polypropylene and high- and low-density polyethylene, the main constituents in municipal waste, those plastics work especially well for capturing CO2 when treated with potassium acetate.

The lab estimates the cost of carbon dioxide capture from a point source like post-combustion flue gas would be $21 a ton, far less expensive than the energy-intensive, amine-based process in common use to pull carbon dioxide from natural gas feeds, which costs $80-$160 a ton.

Like amine-based materials, the sorbent can be reused. Heating it to about 75 degrees Celsius (167 degrees Fahrenheit) releases trapped carbon dioxide from the pores, regenerating about 90% of the material’s binding sites.

Because it cycles at 75 degrees Celsius, polyvinyl chloride vessels are sufficient to replace the expensive metal vessels that are normally required. The researchers note the sorbent is expected to have a longer lifetime than liquid amines, cutting downtime due to corrosion and sludge formation.

To make the material, waste plastic is turned into powder, mixed with potassium acetate and heated at 600 C (1,112 F) for 45 minutes to optimize the pores, most of which are about 0.7 nanometers wide. Higher temperatures led to wider pores. The process also produces a wax byproduct that can be recycled into detergents or lubricants, the researchers say.

The Department of Energy and Saudi Aramco supported the research.

Source: Rice University