The genes of Europeans reflect the dietary shifts that occurred with the rise of farming, report researchers.

Before the Neolithic revolution, European populations were hunter-gatherers who ate animal-based diets and some seafood. But after the advent of farming in southern Europe around 8,000 years ago, which spread northward thereafter, European farmers switched to primarily plant-heavy diets.

Researchers collected data from more than 25 other studies that examined ancient DNA from fossils and archaeological remains (dating back to 30,000 years ago until about 2,000 years ago), and DNA from contemporary populations.

The study finds that adaptations occurred in an important genomic region that includes three fatty acid desaturase (FADS) genes. Different versions of the same FADS1 gene, called alleles, corresponded to the types of diets that were adopted.

“The study shows what a striking role diet has played in the evolution of human populations,” says Alon Keinan, associate professor of computational and population genomics at Cornell University and senior author of the paper in Nature Ecology and Evolution. Kaixiong Ye, a postdoctoral researcher in Keinan’s lab, is the paper’s lead author.

“Changing diets instantaneously switched which alleles are advantageous, a result of marked natural selection for the level that a crucial gene is expressed,” Keinan says.

The study has implications for the growing field of nutritional genomics, called nutrigenomics. Based on one’s ancestry, clinicians may one day tailor each person’s diet to her or his genome to improve health and prevent disease.

Did fruit, not friends, give us big brains?

The study shows that plant-heavy diets of European farmers led to an increased frequency of an allele that encodes cells to produce enzymes that helped farmers metabolize plants. Frequency increased as a result of natural selection, where veggie-eating farmers with this allele had health advantages that allowed them to have more children, passing down this genetic variant to their offspring.

The FADS1 gene found in these farmers produces enzymes that play a vital role in the biosynthesis of omega-3 and omega-6 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA). These LCPUFAs are crucial for proper human brain development, controlling inflammation and immune response. While omega-3 and omega-6 LCPUFA can be obtained directly from animal-based diets, they are absent from plant-based diets. Vegetarians require FADS1 enzymes to biosynthesize LCPUFA from short-chain fatty acids found in plants (roots, vegetables, and seeds).

Analysis of ancient DNA revealed that prior to humans’ farming, the animal-based diets of European hunter-gatherers predominantly favored the opposite version of the same gene, which limits the activity of FADS1 enzymes and is better suited for people with meat- and seafood-based diets.

Eat lots of fiber or microbes will eat your colon

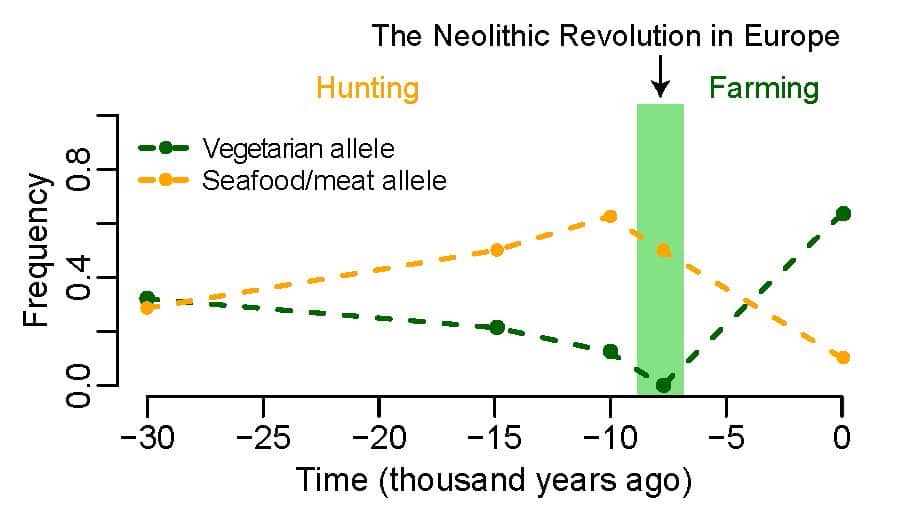

Analysis of the frequencies of these alleles in Europeans showed that the prevalence of the allele for plant-based diets decreased in Europeans until the Neolithic revolution, after which it rose sharply. Concurrently, the opposite version of the same gene found in hunter-gatherers increased until the advent of farming, after which it declined sharply.

The researchers also found a gradient in the frequencies of these alleles from north to south since the Neolithic Era, including modern-day populations. All farmers relied heavily on plant-based diets, but that reliance was stronger in the south, as compared to northern Europeans—whose farmer ancestors drank more milk and included seafood in their diet.

Ofer Bar-Yosef, a Harvard University anthropologist and a coauthor of the study, helped Keinan and Ye scour the anthropological literature for evidence of diets of pre-Neolithic hunter-gatherers and post-Neolithic farmers in different parts of Europe.

“We made predictions based on our evolutionary observations, and then with Ofer’s assistance, we were able to verify them and to conclude that diet was the driving force behind all our evolutionary results,” Ye says.

Plant-based alleles regulate cholesterol levels and have been associated with risk of many diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, cardiovascular disease, arthritis, and bipolar disorder.

“I want to know how different individuals respond differently to the same diet,” Ye says. Future studies will investigate additional links among genetic variation, diets, and health, so that “in the future, we can provide dietary recommendations that are personalized to one’s genetic background,” he adds.

Ye and Keinan previously discovered related patterns in the same genomic region in Indian, African, and some East Asian populations that followed a plant-based diet for hundreds of generations.

The National Institutes of Health and the Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. Foundation funded the work.

Source: Cornell University