Addressing place names in national parks could be a starting point for reckoning with the country’s history of dispossessing Indigenous nations from their lands.

The new paper in the journal People and Nature reveals that derogatory names are only the tip of the iceberg—violence in place names can take many forms. The study quantifies the scale of the problem in US national parks and puts the movement to change place names in context.

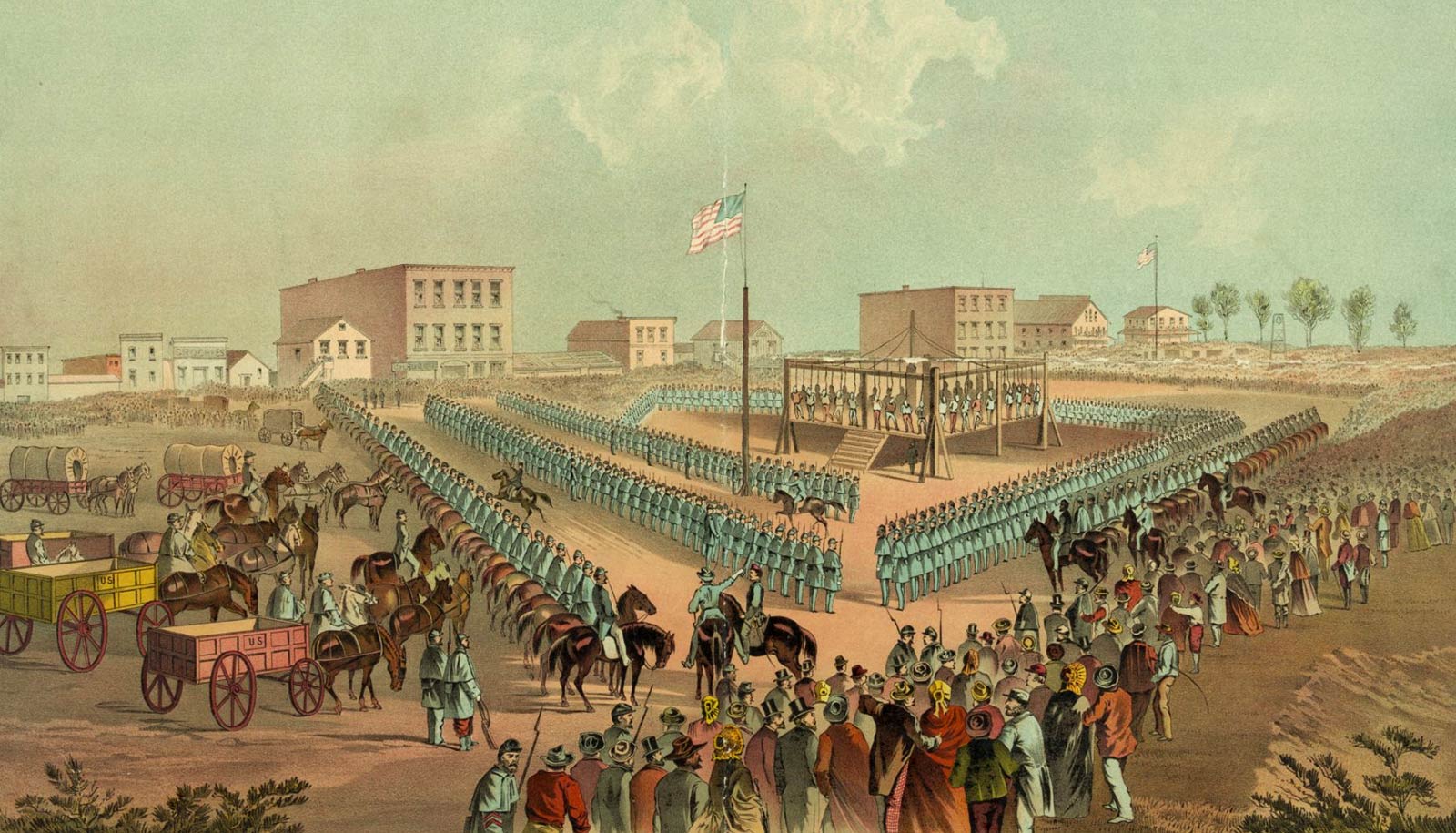

Around the world, statues of historic figures who symbolize colonialism and oppression are being critically examined, and often removed. Across the United States, Confederate figures and statues with clear racist symbolism have been uninstalled or actively torn down. These removals reflect a shifting zeitgeist that seeks to include the history of Indigenous and racialized peoples. But some symbols of oppression are less tangible than a statue.

“To give place names to persons who authorized and who carried out the massacre of approximately 173 of my ancestors in 1870 on the Marias River, Montana is an atrocity…”

US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland recently initiated a task force to address derogatory place names on federal lands, including names using a derogatory term for an American Indian woman. But is everyone on board? Why are place names important?

“As highly visible cultural symbols, place names help us collectively navigate and give meaning to our world,” says coauthor Grace Wu, an assistant professor in the University of California, Santa Barbara’s environmental studies program. “When those names are violent, derogatory, racist, or colonialist, they perpetuate the harms of those violent acts and ideas.”

National parks have been called the country’s “best idea,” but many may not realize how park names can help cover up their violent histories. The authors reviewed more than 2,000 place names in 16 national parks, including Acadia, Yosemite, and the Great Smoky Mountains. Their analysis revealed a striking trend of names that commemorate violence and colonialism while erasing Indigenous cultures.

The researchers identified 52 places named for settlers who committed acts of violence, often against Indigenous peoples. For instance, Mt. Doane, in Yellowstone, and Harney River, in the Everglades, commemorate individuals who led massacres against the areas’ Indigenous peoples, often including women and children.

There were 107 natural features that retained traditional Indigenous names, compared with 205 names given by settlers that replaced traditional names found on record. Most egregious were 10 names using racial slurs.

The authors were astounded by the sheer number of problematic names but were even more surprised by how widespread the issue was. “Every single park we examined had place names that in some way reflect anti-Indigenous ideas,” Wu says.

“The study illustrates that place names in the parks contribute to the erasure of indigenous sovereignty at a systemwide scale and require a systemwide response,” says lead author Bonnie McGill, a conservation research fellow at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

The study supports Secretary Haaland’s task force and future task forces seeking to address more than just derogatory names. “Part of the motivation for this work was to help white settlers and scientists like me better understand some of the changes involved in reckoning with our history of settler colonialism in the US,” McGill says. She stresses the importance of placing settler history in conversation with Indigenous histories, rather than just choosing one or the other.

The research team places their work in service to local and national name-changing campaigns. For over a century Native American groups, like the Blackfeet and Lakota, have called for changing place names at national parks and monuments. “The work by Bonnie McGill and her team has shed important light on the true spirit and facts pertaining to national park place names which were in place since time immemorial by our ancestors,” says Oki Nistoo Kiaayo Tamisoowo (Bear Returning over the Hill), also known as Stanley Grier, chief of the Piikani Nation and president of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

Chief Grier supports renaming Hayden Valley as Buffalo Nations Valley and changing Mount Doane to First Peoples’ Mountain; both are located in Yellowstone National Park. “To give place names to persons who authorized and who carried out the massacre of approximately 173 of my ancestors in 1870 on the Marias River, Montana is an atrocity that only perpetuates the illegitimate honor of persons that would be classified as war criminals,” he says.

Even seemingly benign place names can also be problematic. “Places like Clear Creek or Sharp Peak might seem harmless or neutral, but at the minimum they are erasing and replacing traditional Indigenous place names,” explains coauthor Natchee Barnd, a professor of ethnic studies at Oregon State University.

A national campaign inspired by the team’s research, WordsAreMonuments.org, was launched by social justice pop-up museum The Natural History Museum, a program of the organization Not An Alternative. The Wilderness Society and National Association of Tribal Historic Preservation Officers has also published a new guide on how individuals can change place names.

“The systemic nature of problematic places names requires systemic, rather than piecemeal, solutions,” Wu says.

Source: UC Santa Barbara