The unique circumstances arising from the COVID-19 pandemic altered a long-held convention that doctors provide care regardless of personal risk.

In a study assessing doctors’ tolerance for refusing care to COVID-19 patients, researchers identified a growing acceptance to withhold care because of safety concerns.

“All the papers throughout history have shown that physicians broadly believed they should treat infectious disease patients,” says Braylee Grisel, a fourth-year student at Duke University School of Medicine, and lead author of the study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

“We figured our study would show the same thing, so we were really surprised when we found that COVID-19 was so different than all these other outbreaks,” Grisel says.

The researchers analyzed 187 published studies culled from thousands of sources, including academic papers, opinion pieces, policy statements, legal briefings, and news stories. Those selected for review met criteria for addressing the ethical dilemma posed by treating a novel infectious disease outbreak over the past 40 years.

Most articles—about 75%—advocated for the obligation to treat. But COVID-19 had the highest number of papers suggesting it was ethically acceptable to refuse care, at 60%, while HIV had the least number endorsing refusal of care at 13.3%.

The trendline stayed relatively stable across outbreaks occurring from the 1980s until the COVID-19 pandemic hit—with just 9% to 16% of articles arguing that refusing care was acceptable.

What changed with COVID? The authors found that labor rights and workers’ protections were the chief reasons cited in 40% of articles during COVID, compared with only about 17%-19% for other diseases. Labor rights were cited the least often for HIV care, at 6.2%.

Another significant issue cited during the COVID pandemic was the risk of infection posed to doctors and their families, with nearly 27% of papers discussing this risk, compared to 8.3% with influenza and 6.3% for SARS.

“Some of these results may be because we had the unique opportunity to evaluate changing ethics while the pandemic was actively ongoing, as COVID-19 was the first modern outbreak to put a significant number of frontline providers at personal risk in the United States due to its respiratory transmission,” says senior author Krista Haines, assistant professor in the surgery and population health sciences departments.

The authors note that the COVID pandemic had several unique characteristics that collectively altered the social contract between doctors and patients, potentially driving changes in treatment expectations. Such factors included:

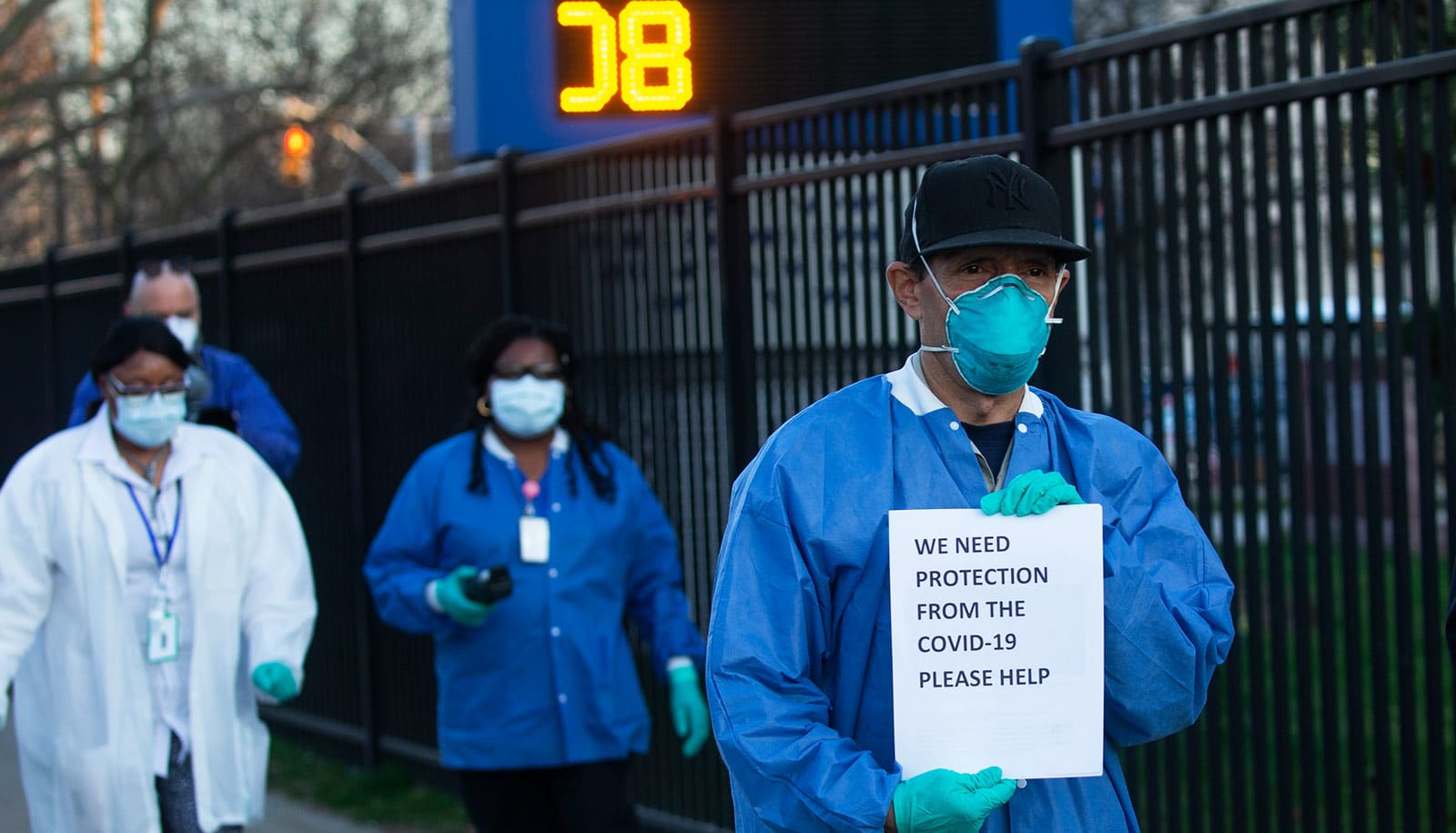

- Shortages of resources available to care teams, including personal protective gear, hospital rooms, respirators, treatments, and vaccines

- Polarizing misinformation about vaccines, effective treatments, and how the virus spread

- Increased rates of reported mistreatment against staff from patients and their family members

The authors note the ongoing debate over whether vaccination status should be considered in the decision to treat a patient.

“There was a great deal of discussion among frontline providers and ethicists on how best to allocate scarce resources,” the authors write.

“Patients who refused vaccination were at a higher risk of complications while also putting other patients and providers at risk. Arguments were made based on reciprocity, medical triage, and personal responsibility to exclude patients who refused vaccines from consideration when ventilators and other resources were limited.”

The study’s finding provides insight regarding how care should be provided in future pandemics, Grisel says. What had been a fairly solid expectation that physicians were obligated to provide care despite the risks to themselves now appears to have softened. It is unclear how these results may change in the future when the pandemic is less of an active threat.

“This study really shows how outside pressures in the sociopolitical sphere influence and affect doctors and care providers,” Braylee Grisel says. “In future pandemics, we may need to become more aware of how the risks and outside pressures of an active pandemic influence willingness to provide care.”

Source: Duke University