Sonar technology has inspired a fast, cheap way to determine if water is safe to drink, researchers report.

Based on initial results, scientists say it’s possible to determine changes in the physical properties of liquids.

“If the water isn’t drinkable, then our method will tell you that something is wrong with the water,” says Luis Polo-Parada, an associate professor of pharmacology and physiology in the University of Missouri School of Medicine and investigator at the Dalton Cardiovascular Research Center.

“For instance, if a facility removes salt from sea water in order for water to be safe for drinking, our method can help alert the facility to potential changes such as an issue with the desalination process.”

The photoacoustic effect

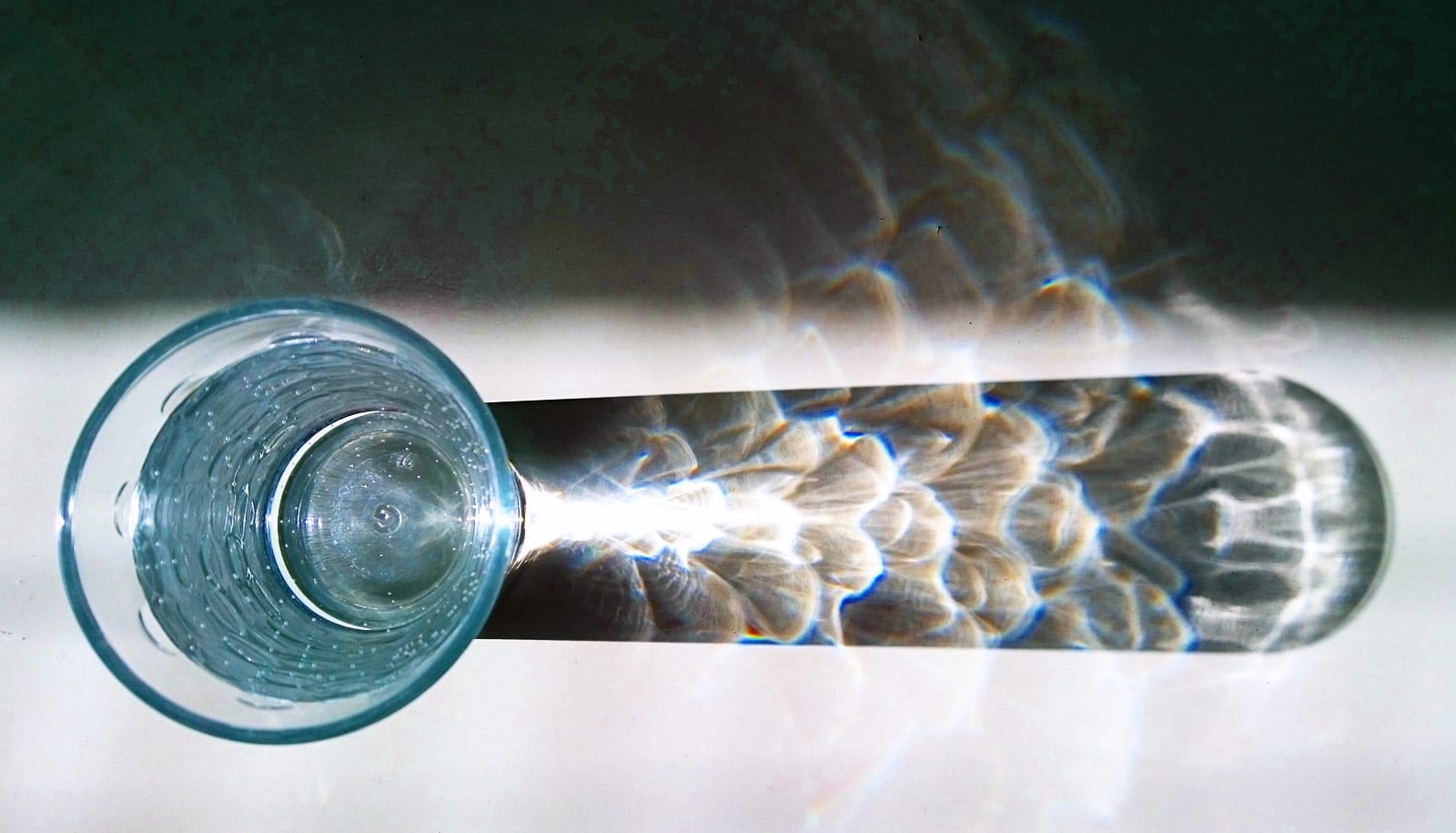

Researchers designed the instrument to analyze the quality of liquids using the photoacoustic effect, or the generation of sound waves after light absorbs in a material. Scientists used drops of sea water, dairy milk, and ionic liquids, a class of molten salt, in the study. They say they believe this might be the first use of the technology to analyze such small liquid samples.

“Let’s use cymbals as an analogy,” says Gary A. Baker, associate professor of chemistry. “Sunlight causes the cymbals to heat up and create a constant ringing sound. Here, on a much smaller scale, we create the same effect by sending flashes of laser light at our tiny homemade cymbal, which is the tape, and measure the speed of the sound that is generated.”

How does it work?

A tattoo removal laser machine sends out a series of brief flashes of light each lasting about 10 nanoseconds. The flashes of light travel through a fiber optic cable wrapped on one end with paint-on liquid electrical tape. The cable’s end, submerged in the liquid, converts the laser light into sound. A microphone records the sound and the data is analyzed in real time.

The team is working to refine its recording methods and equipment to provide commercial industries with an inexpensive way to monitor the quality of liquids, such as the percentage of alcohol in alcoholic beverages, the amount of inferior oil in fraudulent olive oils, the quality of honey, and the amount of sugar or sugar substitutes in soft drinks. They plan to publish updated results later this year.

Additional authors of the paper, which appears in Sensors and Actuators, B: Chemical, are from the University of Missouri and the Universidad de Guanajuato, Mexico. Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología-México partially funded the work.

Source: University of Missouri