When someone gets Salmonella, their body’s own inflammatory response can make things worse by waking up viruses called bacteriophages.

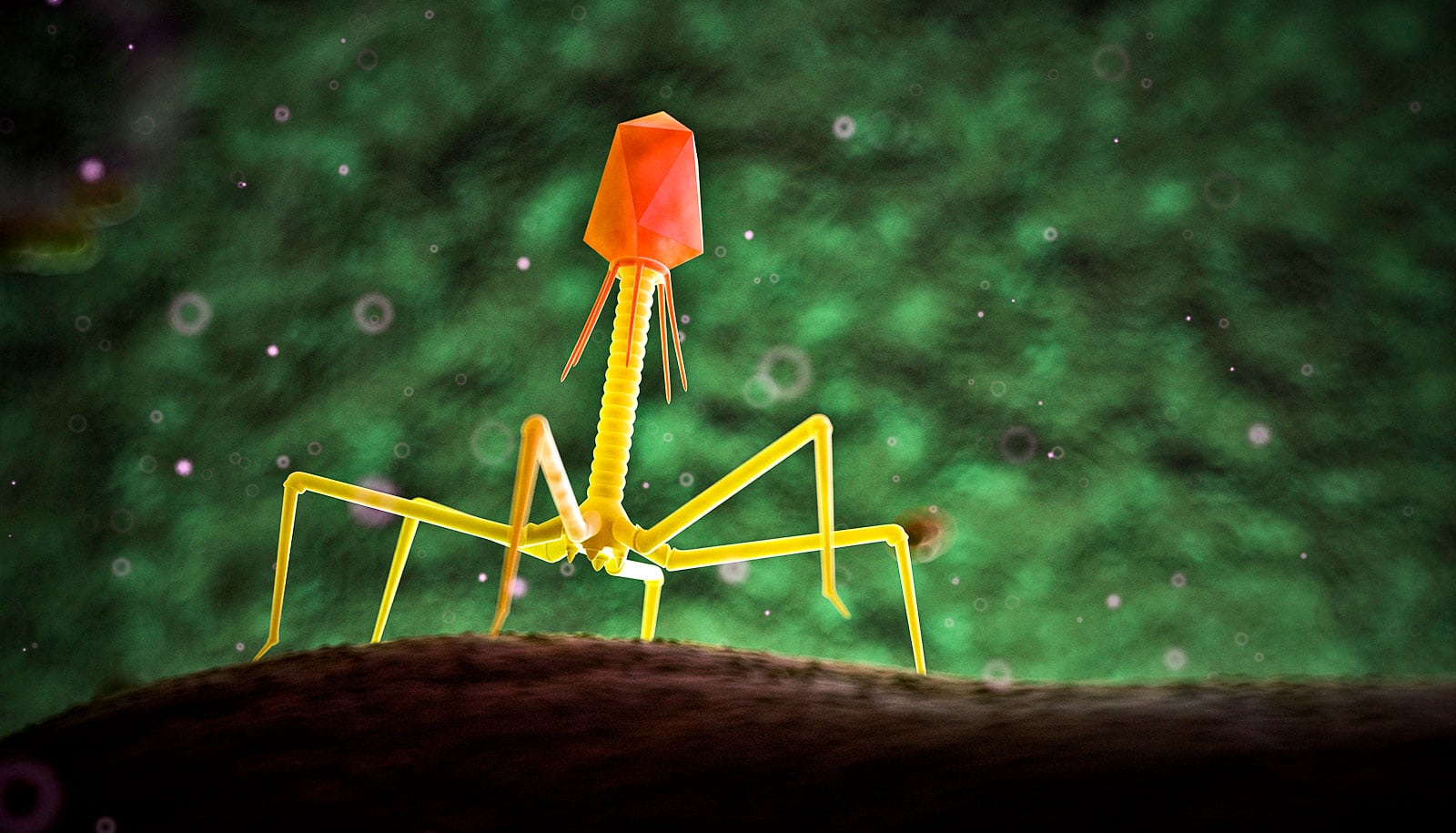

These viruses, also known as phages, can infect Salmonella and transfer genes that give it new properties and make it more toxic, according to a new study published in Science.

As soon as the bacteria cell is attacked by inflammatory factors such as reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, it sets off an SOS signal, which starts the cell’s own repair program. This signal is used as a wake-up by the phages lying dormant in the genome.

“Our results show that the inflammation of the intestine promotes the horizontal gene transfer through phages—an important evolutionary mechanism of microorganisms,” explains Wolf-Dietrich Hardt, the ETH Zurich professor who led the study.

As long as the inflammation persists, the freshly infected Salmonella also produce more phages that in turn infect more Salmonella. This chain reaction can only be prevented if the adaptive immune system intervenes. It sends specific antibodies to neutralize Salmonella at the site of infection.

‘That surprised us’

To find out how quickly temperate phages spread out within a Salmonella population, the researchers infected mice with two different strains of Salmonella. One strain carried the “SopEΦ” phage, while the other did not.

Salmonella triggered an inflammation in the animals’ intestine, which led to a major change in the Salmonella strain carrying phage genes: the phage genes were expressed, the phage multiplied, and ultimately free phage particles were released, killing the Salmonella cell.

Free phages swarmed out and entered the second Salmonella strain to further increase there. In this way, the phages transferred their genes to almost all Salmonella cells of any strain that had previously been free of phage genes.

This horizontal gene transfer sometimes took only three days to complete.

“Phages are ‘selfish’. Therefore one may regard Salmonella diarrhea as a collateral damage of phage evolution.”

“The gene transfer is extremely efficient. That surprised us,” says Hardt, who had not expected such a rapid spread of infection into naive Salmonella strains.

This risk of phage release can be alleviated by vaccination: Salmonella in vaccinated animals is prevented from triggering a bowel inflammation. Incidentally, this also prevents the SOS response and the production of phages.

This tiny sensor spots salmonella in minutes, not days

Médéric Diard, a postdoc at ETH Zurich who carried out the study, proposes that phages could take “control” of the bacteria so that they trigger inflammation ever more efficiently. This also promotes phage reproduction n the intestine.

This link may explain why many phages transfer toxin genes to the bacteria. Phage-encoded toxic substances may create the very conditions in the intestine of victims that stimulate phage production.

“Phages are ‘selfish’. Therefore one may regard Salmonella diarrhea as a collateral damage of phage evolution,” says Hardt.

Another example: Cholera

Cholera has become a deadly cause of diarrhea worldwide. This wasn’t always the case. The original ancestor of Vibrio cholerae was a harmless brackish water bacterium off the coast of Bangladesh.

A phage infected these bacteria and integrated into their genome, including the cholera toxin. This turned the harmless bacterium into a powerful pathogen. The acquisition of the cholera toxin gene obviously provides this bacterium with an evolutionary advantage.

Today, the bacterium has spread around the world and can cause deadly outbreaks, particularly after natural catastrophes or in areas of conflict where there is poor hygiene.

Source: ETH Zurich