Perovskite films tend to crack easily, but a new study shows that a little bit of heat or compression can easily heal those cracks.

That bodes well for the possibility of using inexpensive, but fragile, perovskite materials to replace or complement pricey silicon in solar cell technologies, researchers say.

“The efficiency of perovskite solar cells has grown very quickly and now rivals silicon in laboratory cells,” says Nitin Padture, a professor in the School of Engineering at Brown University and director of the Institute for Molecular and Nanoscale Innovation.

“Everybody’s chasing high efficiency, which is important, but we also need to be thinking about things like long-term durability and mechanical reliability if we’re going to bring this solar cell technology to the market. That’s what this research was about.”

Cheap perovskites come at a cost

Scientists first incorporated perovskites, a broad class of crystalline materials, into solar cells in 2009. Those first perovskite solar cells had a power conversion efficiency of around 4%, but now that exceeds 25%—essentially the same as traditional silicon.

The advantage of perovskite solar cells is that they can be made for a fraction of the cost of silicon, potentially cutting the cost of solar power installations. Researchers can also make perovskites into thin films that are semi-transparent and flexible, potentially clearing the way for energy-generating windows or for lightweight, flexible solar cells in tents or backpacks.

But the low-cost and ease of making perovskite solar cells comes with a cost.

“In material science, things that are easy to make also tend to be easy to break,” says Padture, lead author of the paper in Acta Materialia. “That’s certainly true of perovskites, which are quite brittle. But here we show they’re also quite easy to fix—cracks in perovskite films can be healed by compressing them or with moderate heat.”

Total repair

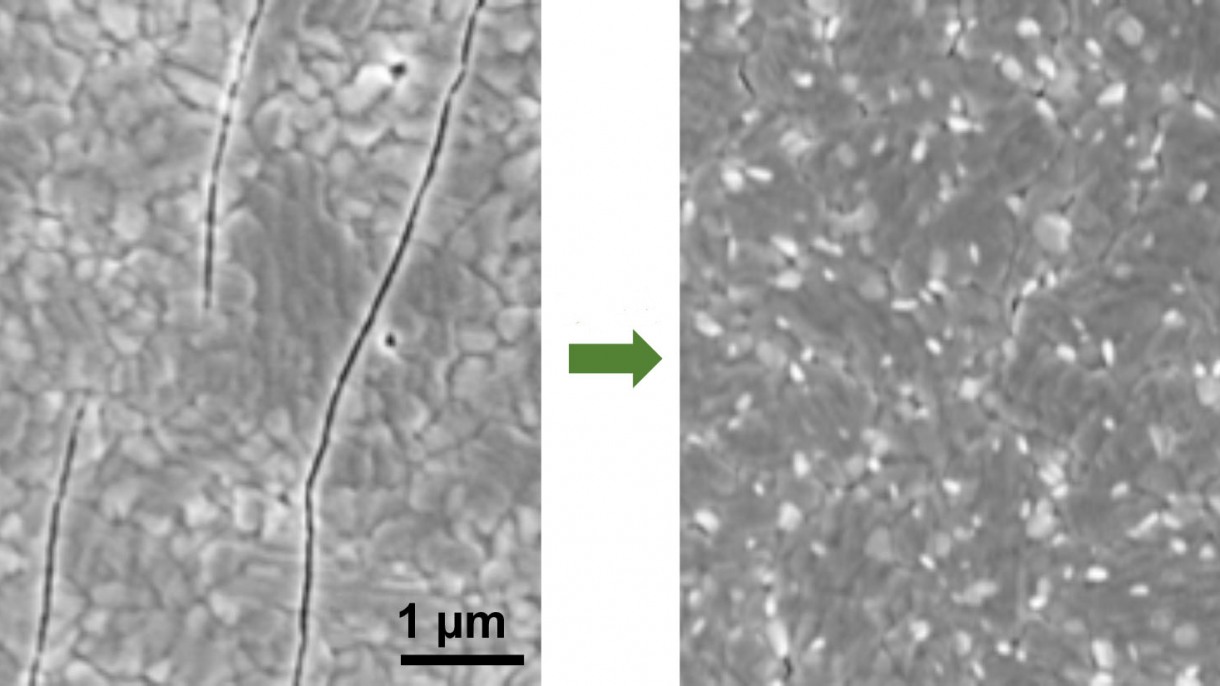

For the study, first author Srinivas Yadavalli, a doctoral student working in Padture’s laboratory, deposited perovskite films on plastic substrates. He then bent the substrate to put tensile (pulling apart) stress on the perovskite film while using a scanning electron microscope (SEM) to detect cracks. Once the film cracked, the researchers then bent the substrate in the opposite direction to see if compressive stress might heal those cracks.

Sure enough, SEM imaging showed that the cracks disappeared. To make sure the cracks truly fully healed and were not merely hidden, the researchers used a technique known as X-ray diffraction. Measuring the size of a material’s atomic lattice can reveal whether a formerly cracked area can carry a mechanical load—a surefire sign that the crack healed. Those tests also indicated fully healed cracks.

The researchers found that heat was just as effective in healing cracks. Temperatures around 100 degrees Celsius—quite modest heating by material science standards—completely healed cracks in perovskite films.

The research aimed to better understand the basic properties of perovskite materials. Researchers say they need to do more work to develop methods of applying the information in a commercial setting, but knowing that perovskite films easily heal could be useful as these kinds of solar cells move toward commercialization.

“It’s good news,” Padture says. “It suggests that fairly simple healing methods may help maintain performance in these kinds of solar cells.”

The Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation funded the work. Researchers used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated by Argonne National Laboratory.

Source: Brown University