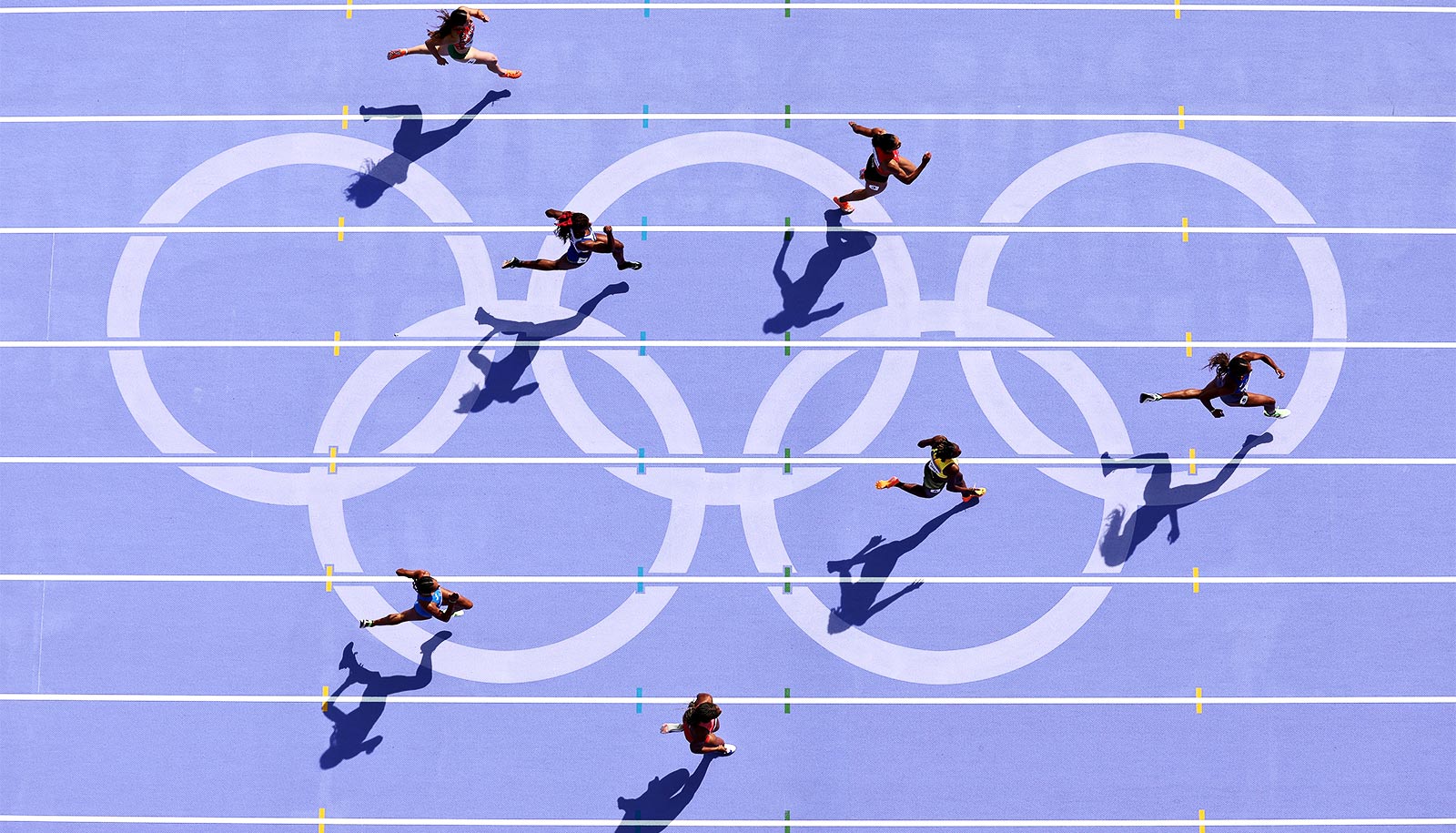

Every millisecond matters for the athletes gathered in Paris for the Summer Olympics, and track and field athletes compete on a surface designed to produce record-breaking performances.

Mondo athletic tracks have been underneath the feet of Olympians since 1972. In that time, 300 records were broken on surfaces designed and constructed in Alba, Italy.

Georgia Tech’s George C. Griffin Track and Field Facility was outfitted with a Mondo track before the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta to serve as the workout track for the Olympic Village, and the material has been a staple at the facility ever since. Track and field coach Grover Hinsdale explains that the consistency in Mondo’s construction sets it apart from all other tracks.

“A Mondo track is made in a climate-controlled factory, processed from the raw rubber to the finished product. So, every square inch of Mondo is the same—same durometer, same thickness, everything is the same. All other rubberized track surfaces are poured on-site, so variables like temperature and humidity affect the result, and you may end up with lanes that don’t set uniformly,” he says.

Hinsdale likened the installation process to laying carpet. It took more than 2,800 glue pots to set the 13,000 square meters (139930.84 square feet) of track inside Stade de France.

Jud Ready, a principal research engineer in the School of Materials Science and Engineering at Georgia Tech, says the evolution of the company’s technology has also contributed to producing faster tracks.

“They’re able to alter the rubber track’s energy return mechanism by changing the shape of the particulate and the compressibility of it,” Ready says. “Longevity is less of a concern for the Paris track, so they can tune it to emphasize speed.”

Each layer of the track surface plays a different role in helping athletes achieve peak performance. Hinsdale describes how those layers come together with each step.

“When your foot strikes down on an asphalt surface or you’re running down a sidewalk, there’s virtually no give other than what’s taking place in the muscles and joints of your body. The surface is giving nothing back. When your foot strikes a Mondo surface, it’ll sink in slightly, and the surface gives energy back. This pushes your foot back off that track quicker, putting the foot back into the cycle to complete another stride,” he says.

Because of the energy given back by the thin and firm surface of the Mondo track, Hinsdale says, sprinters and distance runners will run faster with the same effort they normally exert on any other surface.

Athletes look for every edge to get ahead of the competition. Ready’s course, Materials Science and Engineering of Sports, examines how that advantage can be found at the scientific level.

“All sports are so heavily driven by material advancements these days,” he says. “Yes, we use the mechanical properties we’ve used since the Egyptians started racing chariots, but as material scientists, we keep trying to make things better.”

Viewers have noticed the unique purple hue of the Paris track, but Ready and Hinsdale don’t expect the striking color to affect performance.

Source: Georgia Tech