When rivers are formed and branch into smaller streams, the streams with the strongest current expand, while others run dry and eventually disappear. The same happens with the formation of some human organs, new research shows.

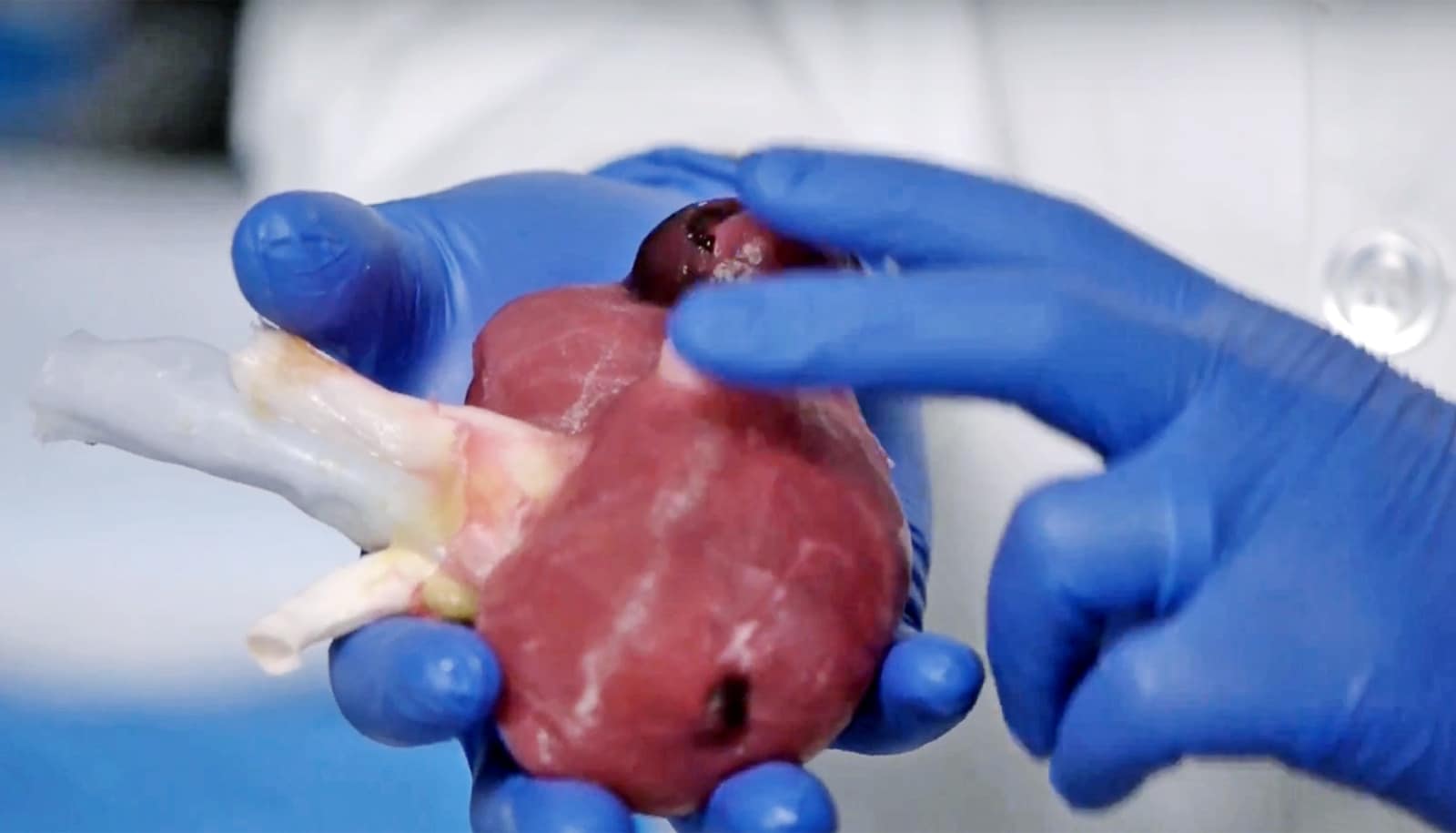

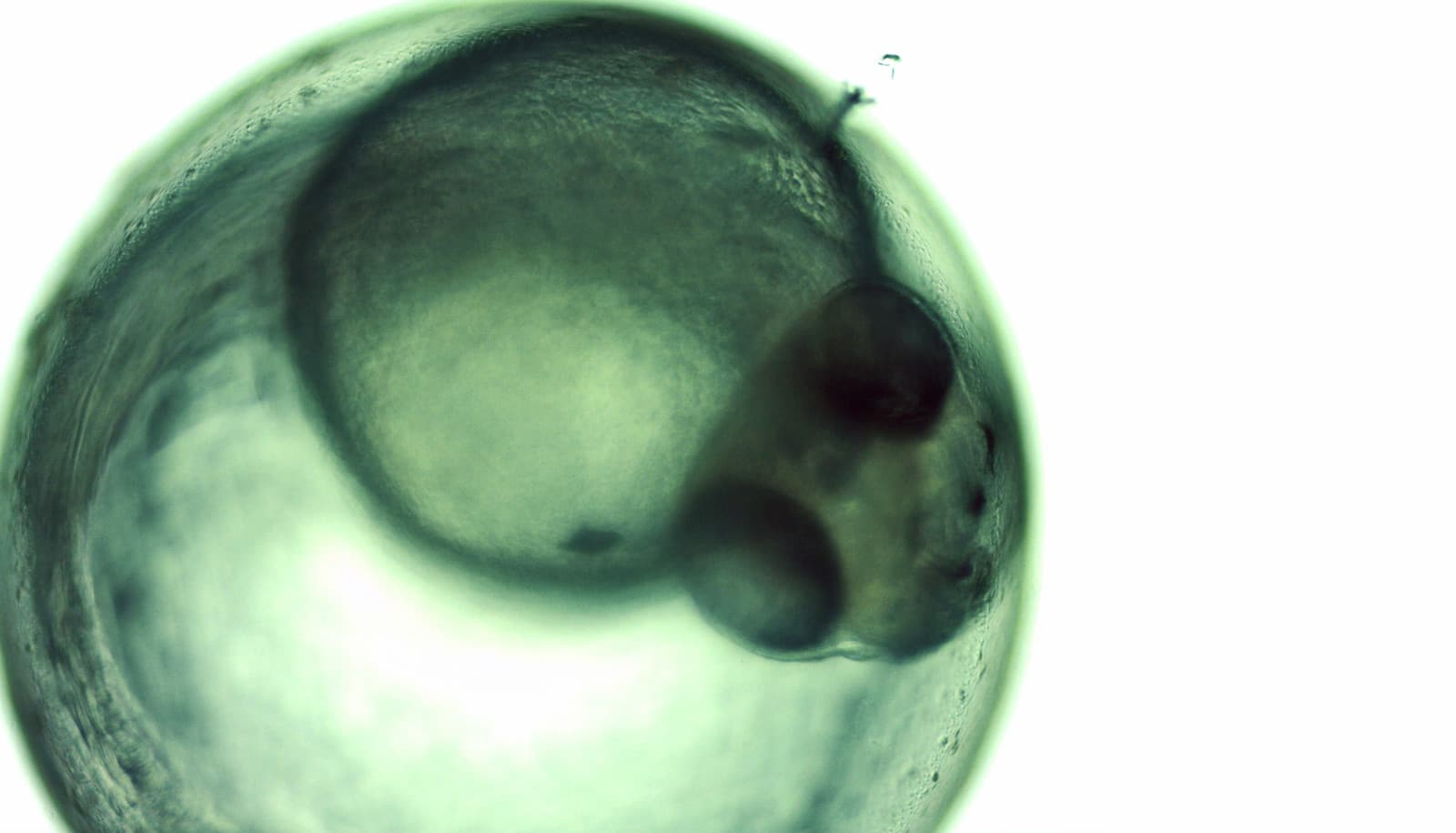

To explore the idea further, researchers studied the pancreas in mouse embryos and looked at how the organ develops from embryo stage until the mouse is born.

Enzyme producer

A well-functioning pancreas is essential to digest food. The organ produces enzymes that help the body digest and assimilate nutrients. A network of ducts lead the enzymes to the intestines.

Researchers studied the formation of this network using methods originally meant to analyze road and river networks.

“We discovered that even though the shape of the pancreas varies from mouse to mouse, the network of the pancreas is the same across mice at a given developmental stage,” says coauthor, Anne Grapin-Botton, a professor from the Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Stem Cell Biology at the University of Copenhagen.

“At the early developmental stages, the network of ducts resembles a road network in a city, where it is easy to get from one place to another and you can take several roads to reach the same destination. Everything is connected in a superfluous manner. It is convenient, but everything comes at a price. It means that you have to maintain a lot of roads,” she says.

“Towards the end of the development the structure of the network is far more economical and optimal with regard to delivering digestive enzymes to the intestines. The flow of fluid running through the pancreas network to the duodenum causes the ducts with the largest flow to expand and the unnecessary ones to be eliminated—just like the formation of river beds,” Grapin-Botton says.

Testing, testing

The researchers colored the network of ducts using fluorescent antibodies so they could monitor the development of the network and to learn how the ducts connect. This revealed that the pancreas, at an early stage, begins to practice and prepare for after birth. The organ does this, among other things, by doing “test runs” and sending secretion through the network.

“Our study shows how the organ, already at the fetal stage, is able to prepare its form and structure to such a degree that it is ready to work optimally after birth. The organ’s ‘test runs’ make it possible to optimize the network of ducts to secure the most efficient delivery of enzymes to the intestines. The process that we have uncovered in the pancreas may also prove relevant to other similar organs like the salivary gland,” says Grapin-Botton.

This discovery may also lead to better understanding and development of treatments for diseases involving abnormal formation of the duct network, such as what is seen in patients with cystic fibrosis. The disorder, which develops differently from person to person, may prevent pancreas enzymes from reaching the intestines, because the network doesn’t work properly.

“I hope this improved understanding of how the organs form these networks of ducts will enable us to discover how diseases affecting the pancreas emerge (e.g., cystic fibrosis). Patients suffering from some types of diabetes also show cystic or enlarged ducts in the pancreas and other organs such as the kidneys and liver. This study is a step in the direction of better understanding the link between enlarged ducts and diabetes,” says Anne Grapin-Botton.

The research appears in PLOS Biology.

The Danish National Research Foundation, Novo Nordisk Foundation, and the European Research Council funded the work.

Source: University of Copenhagen