Six years after “the Blob” rolled through the Santa Barbara Channel in California, researchers are finding lasting effects in the area’s kelp forest communities.

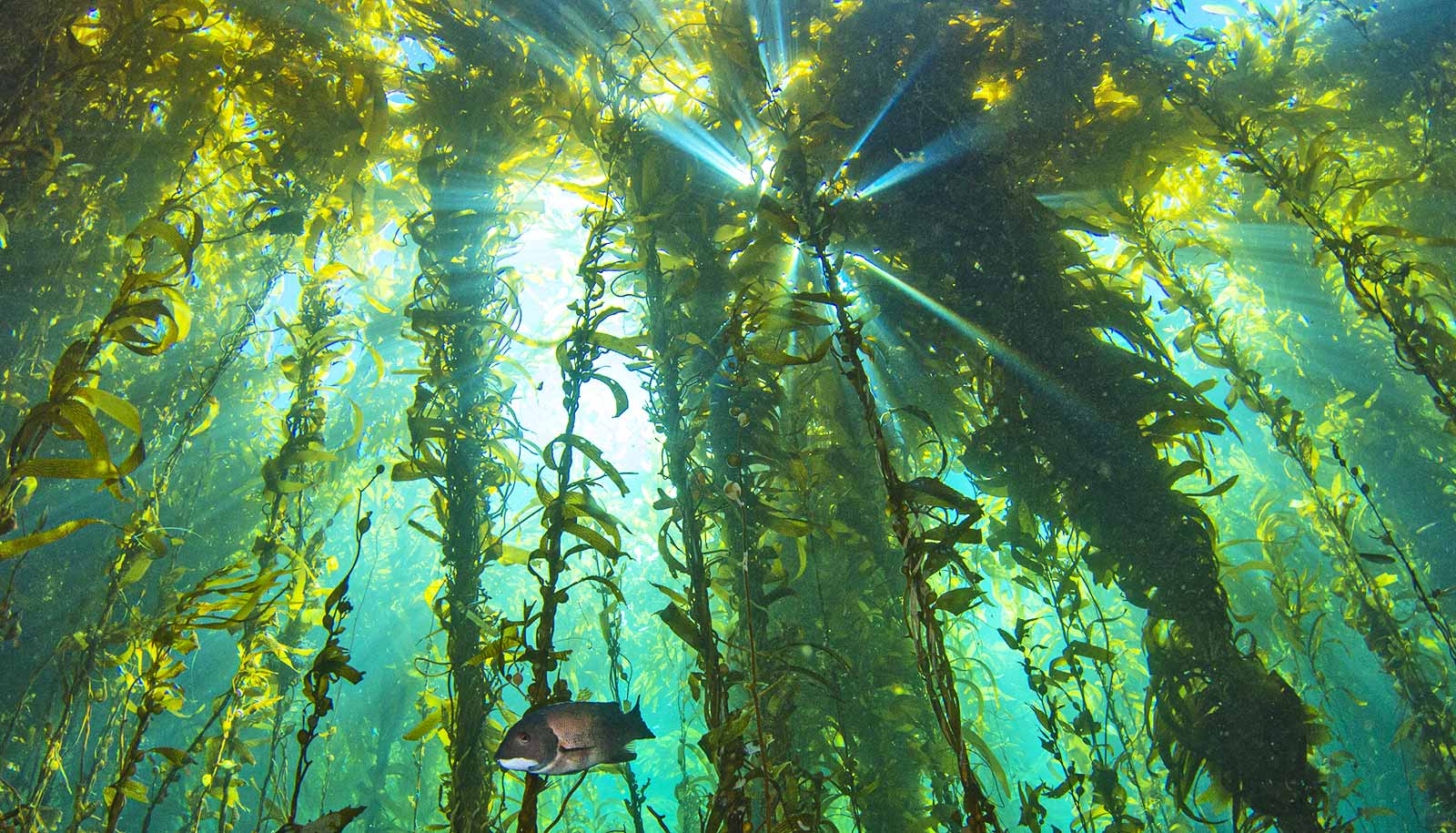

The nearshore rocky reefs of the Santa Barbara Channel are dynamic places, with populations of fish, mollusks, algae, and other assorted sea life shifting in response to currents, storms, and a variety of other conditions.

They wax and wane, typically returning to some sort of baseline composition—a kind of standard demographic—after disturbances temporarily disrupt the neighborhood, and then subside.

The Blob, an extreme marine heatwave that rolled through the Pacific Ocean, consisted of abnormally warm temperatures that blanketed the waters in the Channel from 2014–2016. The Blob wreaked havoc on reef inhabitants, especially sessile invertebrates—filter feeders attached to the nearshore rocky reefs, such as anemones, tubeworms, and clams.

“As sessile animals, most species are permanently attached to the substrate as adults,” says Kristen Michaud, a graduate student researcher at the University of California, Santa Barbara and lead author of the study that appears in Communications Biology. “They cannot forage for alternate food sources and are highly dependent on the delivery of plankton.”

Six years later, the number of these creatures has bounced back, but a closer look reveals that the structure of these populations has changed—an indicator of the effects of global warming on coastal oceans.

Marine heatwaves aren’t unheard of

Marine heatwaves in the Santa Barbara Channel “tend to be associated with El Niño events,” says coauthor Dan Reed, a coastal marine ecologist. During these events, surface temperatures across the Pacific Ocean rise by a few degrees, and the typical upwelling of nutrient-rich cold water from the deep is suppressed. This affects the abundance of phytoplankton in the surface waters that rely on these nutrients, and by extension, the many sea creatures that rely on the plankton for food.

In the Channel, El Niños tend to come with big winter storms that rip out kelp and scour the rocky sea floor. These events are destructive, but are a normal part of life in the Channel’s kelp forests—the sites of UC Santa Barbara’s Santa Barbara Coastal Long-Term Ecological Research (SBC LTER) project.

“What was really different about the Blob was that in 2014 and 2015, we got all this warm water, but without the swell,” Reed says. This made it easier to suss out the effects of increased temperature on the kelp forest community without the complicating factors of storm and wave action, he explains.

“The Blob is exactly the kind of event that shows why long-term research is so valuable,” says coauthor Bob Miller, principal investigator at the SBC LTER. “If we had to react to such an event with new research, we would never know what the true effect was. Because SBC LTER is doing work designed to address how the changes in the environment affect coastal marine ecosystems, we are perfectly positioned to examine unprecedented events like this.”

The anomalous heatwave was a “perfect storm” for the filter feeders, Michaud says. Not only did it result in a reduced abundance of food, but it also stoked the creatures’ metabolisms, leading them to require more food as temperatures rose. As a result, the average cover of sessile invertebrates across the study sites declined by 71% in 2015.

Filter feeder winners and losers

“The groups of animals that seemed to be the winners, at least during the warm period, were longer-lived species, like clams and sea anemones,” Michaud says, explaining that these species could have traits and feeding strategies that enable them to survive periods of stress and low food availability.

The more vulnerable invertebrates were the rapid-growing and shorter-lived types such as sea squirts, sponges, and bryozoans—compound organisms composed of a few to many tiny, specialized individuals.

“But after the Blob, the story is a little different,” Michaud says. “Bryozoan cover increased quite rapidly, and there are two species of invasive bryozoans that are now much more abundant.”

Post-Blob, the species Watersipora subatra, a recent invader, and the long-established Bugula neritina are now more prevalent in the Channel, according to the study.

There could be several reasons for the new dominance of these species, Michaud says, such as a greater tolerance for warmer temperatures compared to the natives, and more aggressive competition for space against reduced numbers of native bryozoans.

The kelp forests, which were surprisingly resilient to the heat in the Santa Barbara Channel, may also have assisted in the bryozoan invaders’ quest for space by shading out competing seaweeds in the understory.

Additionally, Michaud and her colleagues found that a native sessile gastropod called Thylacodes squamigerous, or “scaled worm snail,” has significantly increased in abundance since the onset of the Blob. With a southern range that extends beyond Baja California, the researchers surmise that the animal may have adaptations to warm temperatures that made it robust to the Blob. Its ability to switch to alternative food sources such as kelp detritus could have given it an edge during the phytoplankton lean years.

The reshaping of the sessile invertebrate populations after the Blob are among the many shifts in the kelp forests that Michaud, Miller, Reed, and colleagues at the SBC LTER have focused on, particularly with respect to climate change.

“Nothing’s permanent in this system,” Reed says. “Things fluctuate on the order of months, other things on the order of years.” With the decades’ worth of continuous data collected at the LTER’s study sites, scientists can watch for changes that might otherwise go unnoticed now but in the future could result in more profound effects.

The heat of the Blob may have subsided in the Channel, but the researchers expect the changes it wrought to continue, says Miller, who has an eye on potential effects on the local food web, particularly with animals like surfperch, which forage for sessile invertebrates in the kelp forest.

“This pattern in the community structure has persisted for the entire post-Blob period,” Michaud adds, “suggesting that this might be more of a long-term shift in the assemblage of benthic animals—these communities may continue to change as we experience more marine heat waves and continued warming.”

Source: UC Santa Barbara