Oyster farming along the Delaware Bayshore doesn’t significantly affect four kinds of shorebirds, including the federally threatened red knot, researchers report.

Researchers looked at the red knot (which migrates thousands of miles from Chile annually), ruddy turnstones, semipalmated sandpipers, and sanderlings.

The findings likely apply to other areas around the country including the West Coast and Gulf Coast, areas with expanding oyster aquaculture, researchers say. The study can also play a key role in identifying and resolving potential conflict between the oyster aquaculture industry and red knot conservation groups.

“Our research team represents a solid collaboration between aquaculture research scientists and conservation biologists, and we’ve produced scientifically robust and defensible results that will directly inform management of intertidal oysterculture along Delaware Bay and beyond,” says lead author Brooke Maslo, an assistant professor and extension specialist in the ecology, evolution, and natural resources department in the School of Environmental and Biological Sciences at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

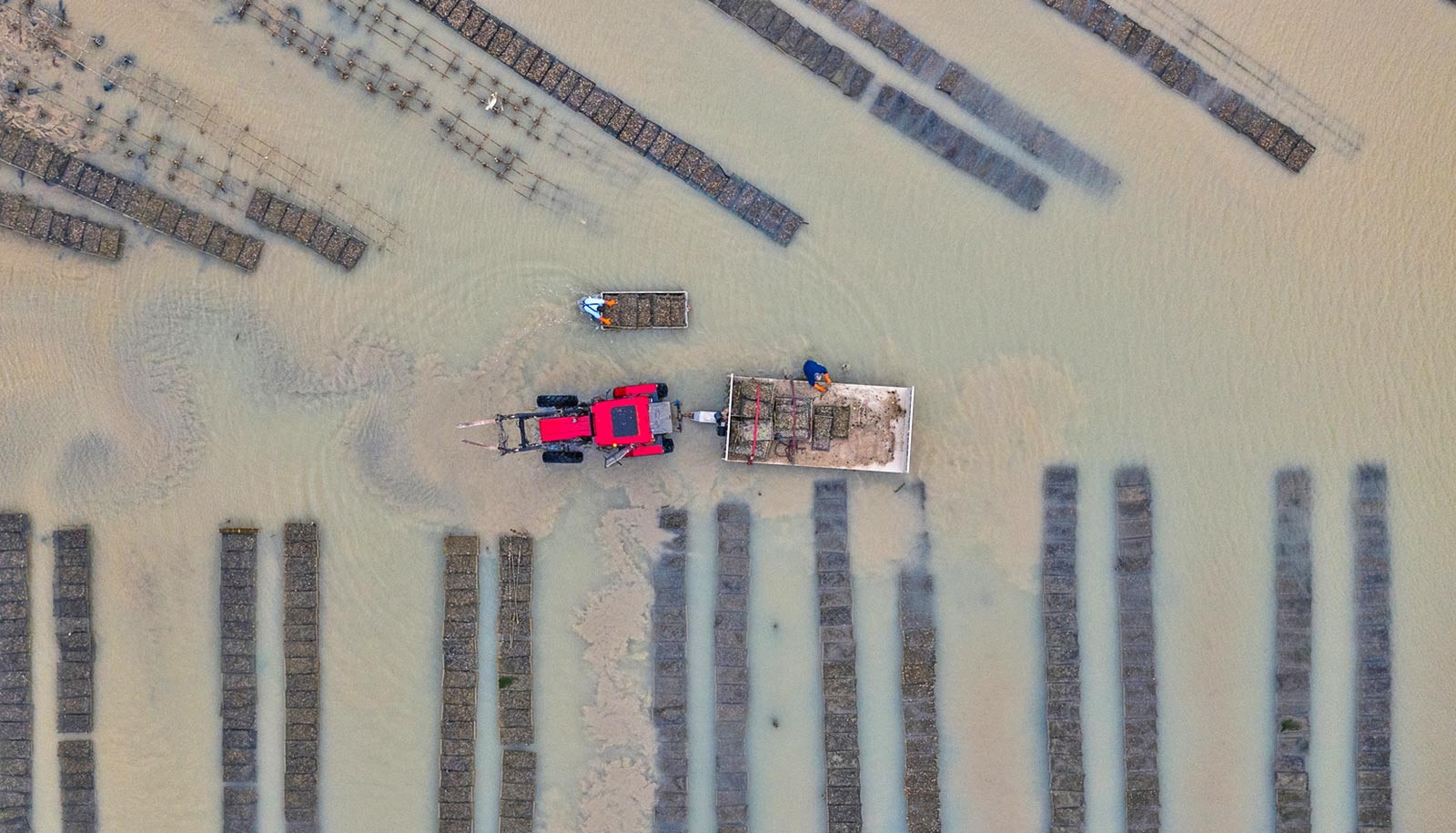

Aquaculture, a burgeoning industry along the Delaware Bayshore, infuses millions of dollars into local economies annually, and the production of oysters within the intertidal flats on Delaware Bay has grown in the last decade.

Although a relatively small endeavor now, rising public interest in boutique oysters for the half-shell market (known as the Oyster Renaissance) and the “low-tech” nature of oyster tending make oyster farming an attractive investment for small-business entrepreneurs.

“Oyster farming has many ecological benefits and is widely recognized as one of the most ecologically sustainable forms of food production,” says coauthor David Bushek, a professor and director of Rutgers’ Haskin Shellfish Research Laboratory in Port Norris, New Jersey.

“Farmers appreciate the ecology around them as they depend on it to produce their crop. The idea that oyster farming might be negatively impacting a threatened species concerns them deeply, so they’ve voluntarily taken on many precautionary measures. They’d like to know which of these measures help and which don’t as they all inhibit their ability to operate efficiently.”

Delaware Bay is a critical stopover area for the red knot, a reddish, robin-sized sandpiper. Every spring, the species feasts on horseshoe crab eggs after journeying from wintering grounds at the southern tip of South America. Red knots then fly to breeding grounds in the Canadian Arctic.

The scientists found that oyster tending reduced the probability of shorebird presence 1% to 7%, while untended aquaculture structures had no detectable impact.

The study shows environmental conditions, especially the presence of gulls or other shorebirds, have the most influence on foraging rates. None of the four bird species of concern substantially altered their foraging behavior due to the presence of tended or untended oyster aquaculture.

Researchers will next investigate how oyster aquaculture may influence interactions between red knots and their main food source, horseshoe crab eggs, as well as how the expansion of oyster aquaculture along the Delaware Bay may affect the availability of foraging habitat at this globally important stopover site.

The study appears in the journal Ecosphere. Additional researchers from Shearwater Analytics and Rutgers contributed to the work.

Source: Rutgers University