A new kind of bioactive “tissue paper” is made of materials derived from organs that are thin and flexible enough to fold into an origami bird.

The technology could potentially be used to support natural hormone production in young cancer patients and aid wound healing.

“It’s versatile and surgically friendly.”

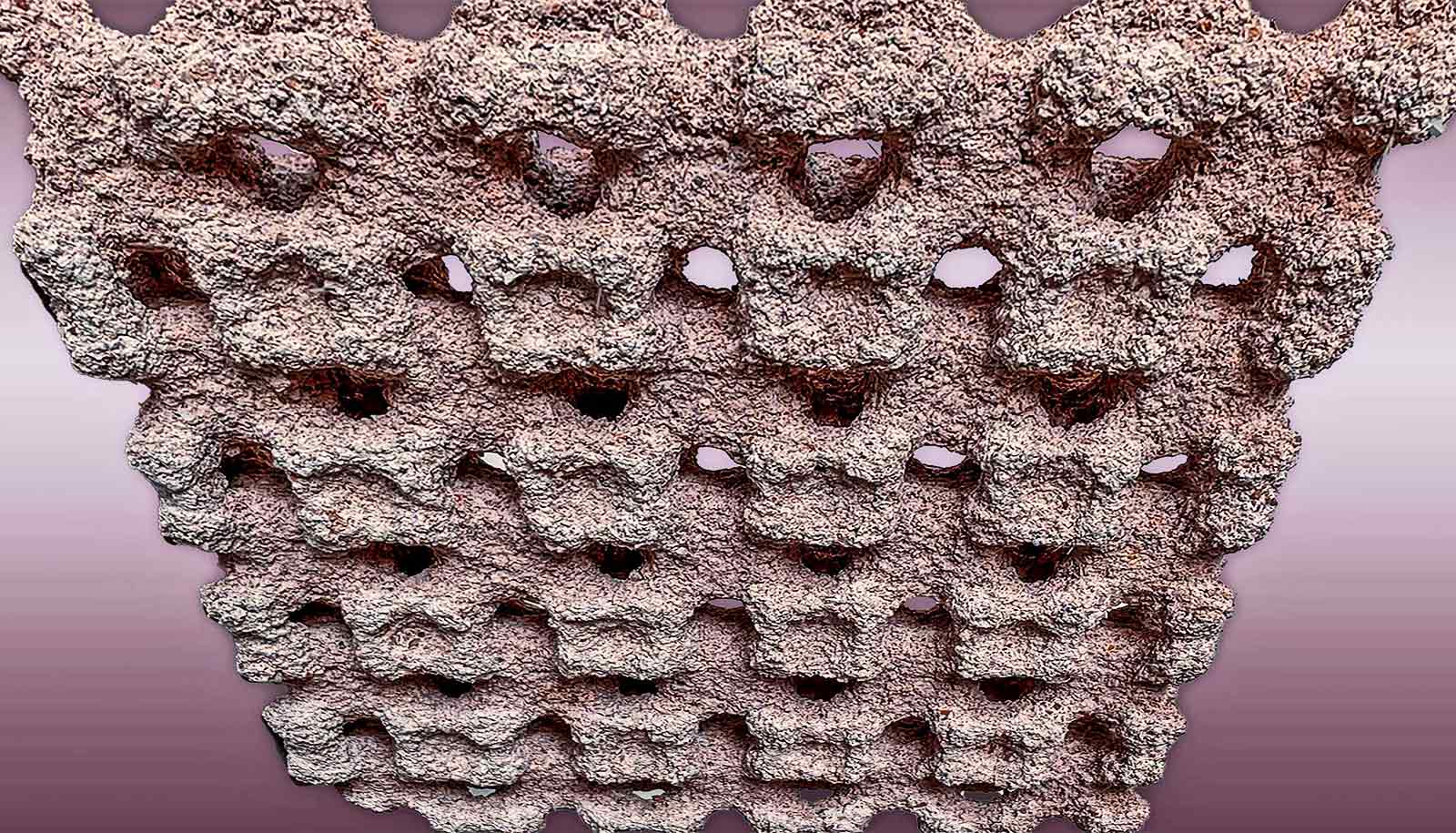

The tissue papers are made from structural proteins excreted by cells that give organs their form and structure and are combined with a polymer to make the material pliable.

For the study, researchers used individual types of tissue papers made from ovarian, uterine, kidney, liver, muscle, or heart proteins obtained by processing pig and cow organs. Each tissue paper had specific cellular properties of the organ from which it was made.

“This new class of biomaterials has potential for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine as well as drug discovery and therapeutics,” says corresponding author Ramille Shah, assistant professor of surgery and assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Northwestern University. “It’s versatile and surgically friendly.”

For wound healing, the tissue paper could provide support and the cell signaling needed to help regenerate tissue to prevent scarring and accelerate healing, Shah says.

The tissue papers are made from natural organs or tissues. The cells are removed, leaving the natural structural proteins—known as the extracellular matrix—that then are dried into a powder and processed into the tissue papers. Each type of paper contains residual biochemicals and protein architecture from its original organ that can stimulate cells to behave in a certain way.

In the lab of reproductive scientist Teresa Woodruff, the tissue paper made from a bovine ovary was used to grow ovarian follicles when they were cultured in vitro. The follicles (eggs and hormone-producing cells) grown on the tissue paper produced hormones necessary for proper function and maturation.

“This could provide another option to restore normal hormone function to young cancer patients who often lose their hormone function as a result of chemotherapy and radiation,” says Woodruff, a coauthor of the study that appears in Advanced Functional Materials.

A strip of the ovarian paper with the follicles could be implanted under the arm to restore hormone production for cancer patients or even women in menopause.

How to turn scar tissue into beating heart cells

Further, the tissue paper made from various organs separately supported the growth of adult human stem cells. Scientists placed human bone marrow stem cells on the tissue paper, and all the stem cells attached and multiplied over four weeks.

“I knew right then I could make large amounts of bioactive materials from other organs.”

“That’s a good sign that the paper supports human stem cell growth,” says first author Adam Jakus, who developed the tissue papers. “It’s an indicator that once we start using tissue paper in animal models it will be biocompatible.”

The tissue papers feel and behave much like standard office paper when they’re dry, Jakus says. He simply stacks them in a refrigerator or a freezer. They can even be folded into an origami bird.

“Even when wet, the tissue papers maintain their mechanical properties and can be rolled, folded, cut, and sutured to tissue,” he says.

An accidental spill of 3D printing ink sparked the invention of the tissue paper. Jakus was attempting to make a 3D printable ovary ink similar to the other 3D printable materials he previously developed to repair and regenerate bone, muscle and nerve tissue. When he went to wipe up the spill, the ovary ink had already formed a dry sheet.

Regeneration could be lurking in our genes

“When I tried to pick it up, it felt strong,” he says. “I knew right then I could make large amounts of bioactive materials from other organs. The light bulb went on in my head. I could do this with other organs.”

“It is really amazing that meat and animal by-products like a kidney, liver, heart, and uterus can be transformed into paper-like biomaterials that can potentially regenerate and restore function to tissues and organs. I’ll never look at a steak or pork tenderloin the same way again.”

Jakus was a Hartwell postdoctoral fellow in Shah’s lab for the study and is now chief technology officer and cofounder of the startup company Dimension Inx, LLC, which Shah also cofounded. The company will develop, produce, and sell 3D-printable materials primarily for medical applications. The Intellectual Property is owned by Northwestern University and will be licensed to Dimension Inx.

The Center for Reproductive Health After Disease of the National Centers for Translational Research in Reproduction and Infertility, Google, and the Hartwell Foundation supported the work.

Source: Northwestern University