A new origami-inspired metamaterial uses “folding creases” to soften impact forces. It could be useful in spacecraft, cars, and more.

Engineers design space vehicles like SpaceX’s Falcon 9 to be reusable. But for that to happen, they have to stick their landings. Landing is stressful on a rocket’s legs because they must handle the force from the impact with the landing pad. One way to combat this is to build legs out of materials that absorb some of the force and soften the blow.

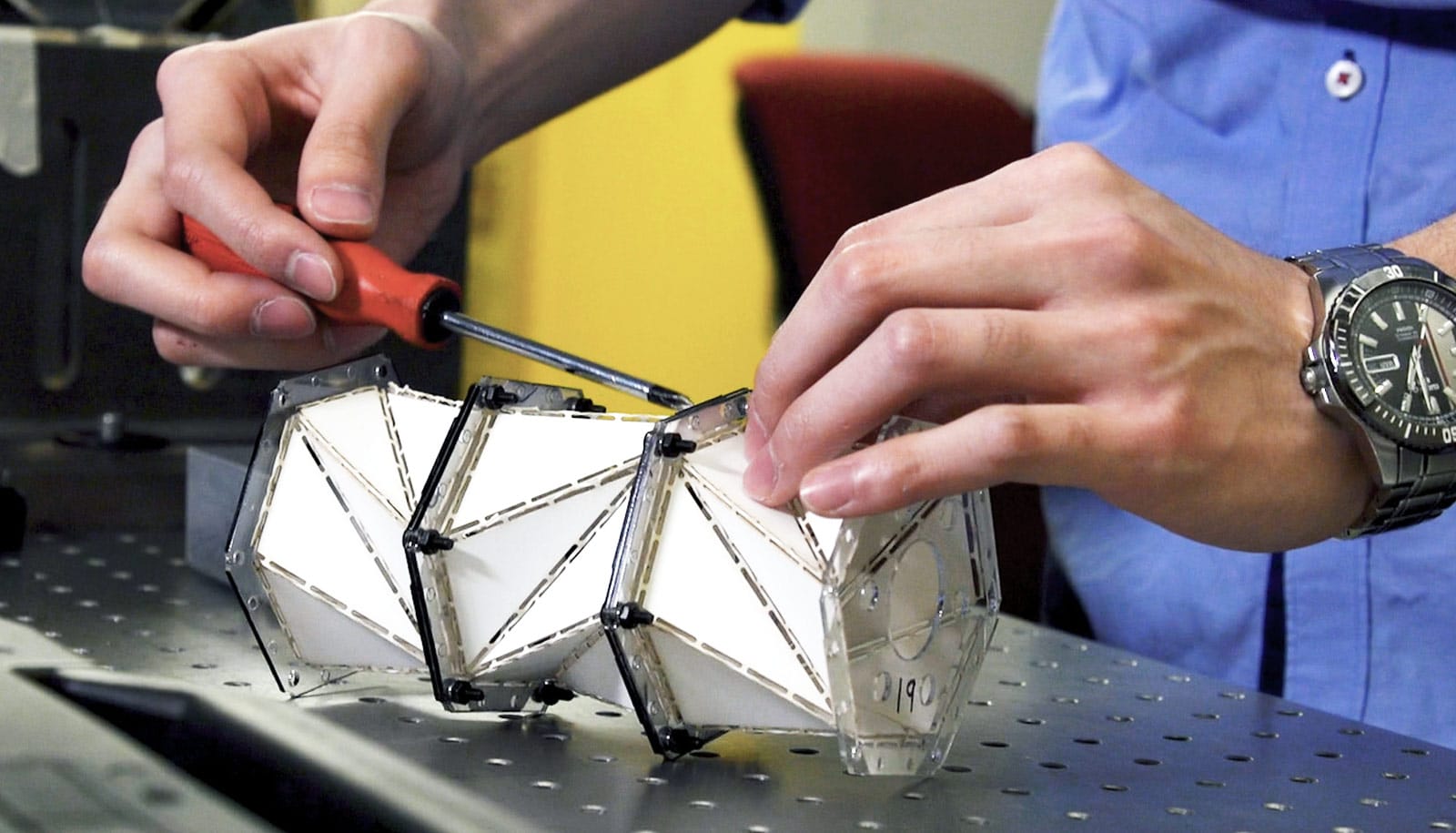

The paper model of the new metamaterial promotes forces that relax stresses in the chain, the researchers report in Science Advances.

“If you were wearing a football helmet made of this material and something hit the helmet, you’d never feel that hit on your head. By the time the energy reaches you, it’s no longer pushing. It’s pulling,” says corresponding author Jinkyu Yang, an associate professor of aeronautics and astronautics at the University of Washington.

Origami metamaterial

Yang and his team designed this new metamaterial to have the properties they wanted.

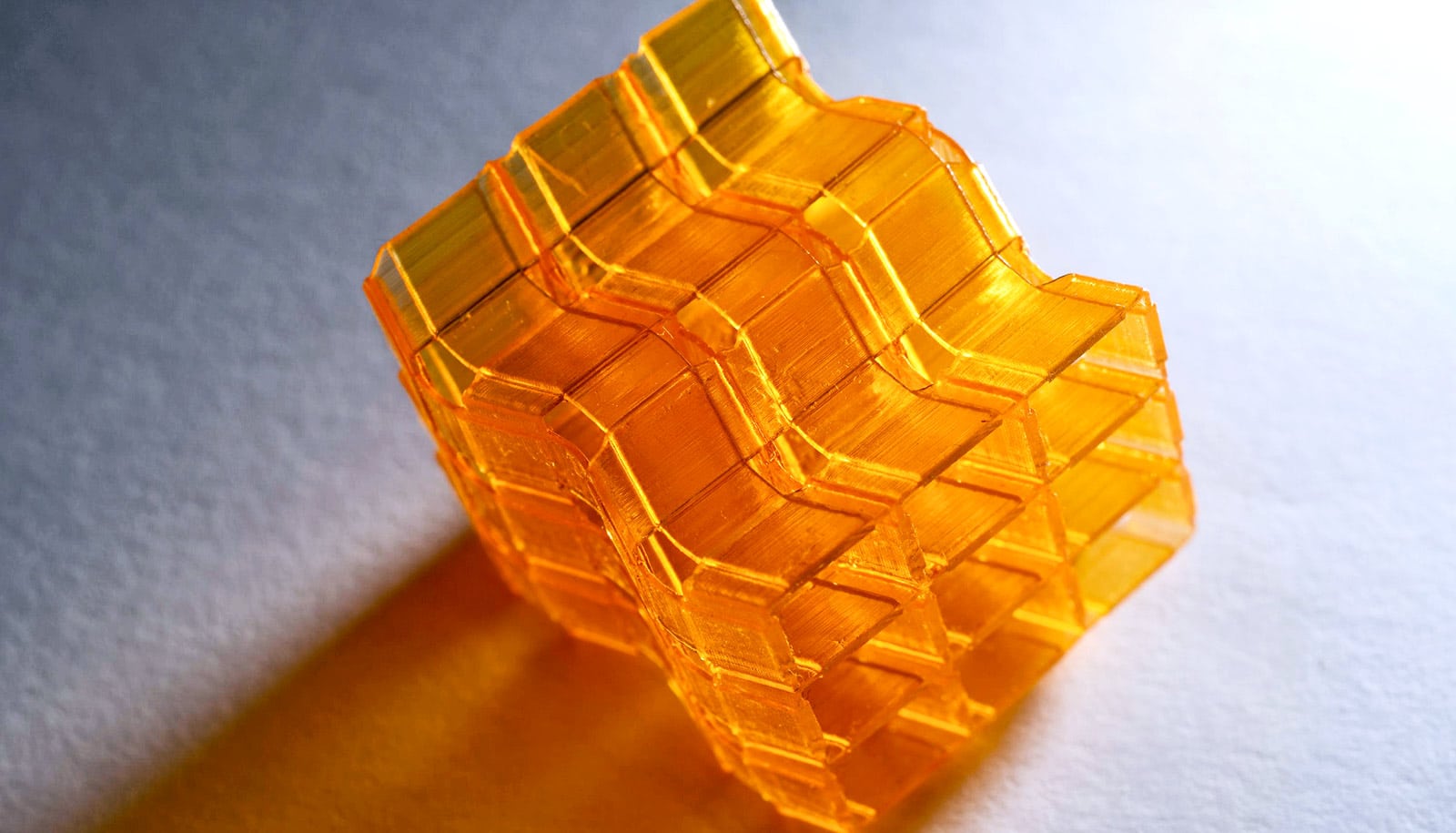

“Metamaterials are like Legos. You can make all types of structures by repeating a single type of building block, or unit cell as we call it,” he says. “Depending on how you design your unit cell, you can create a material with unique mechanical properties that are unprecedented in nature.”

The researchers turned to the art of origami to create this particular unit cell.

“Origami is great for realizing the unit cell,” says coauthor Yasuhiro Miyazawa, an aeronautics and astronautics doctoral student. “By changing where we introduce creases into flat materials, we can design materials that exhibit different degrees of stiffness when they fold and unfold. Here we’ve created a unit cell that softens the force it feels when someone pushes on it, and it accentuates the tension that follows as the cell returns to its normal shape.”

Just like origami, these unit cell prototypes are made out of paper. The researchers used a laser cutter to cut dotted lines into paper to designate where to fold. The team folded the paper along the lines to form a cylindrical structure, and then glued acrylic caps on either end to connect the cells into a long chain.

Testing the origami cells

The researchers lined up 20 cells and connected one end to a device that pushed and set off a reaction throughout the chain. Using six GoPro cameras, the team tracked the initial compression wave and the following tension wave as the unit cells returned to normal.

The chain composed of the origami cells showed the counterintuitive wave motion: Even though the compressive pushing force from the device started the whole reaction, that force never made it to the other end of the chain.

Instead, the tension force replaced it as the first unit cells returned to normal and propagated faster and faster down the chain. So the unit cells at the end of the chain only felt the tension force pulling them back.

“Impact is a problem we encounter on a daily basis, and our system provides a completely new approach to reducing its effects. For example, we’d like to use it to help both people and cars fare better in car accidents,” Yang says.

“Right now it’s made out of paper, but we plan to make it out of a composite material. Ideally, we could optimize the material for each specific application.”

Additional coauthors are from the University of Pennsylvania, Bowdoin College, and the University of Massachusetts. The National Science Foundation, the Office of Naval Research, and the Washington Research Foundation funded the work.

Source: University of Washington