Even when scientists manipulate cells to change how they divide, the shape of a fruit fly’s wing remains the same, researchers report.

The discovery changes the scientific understanding of how organs form, according to a new study, which appears in Current Biology.

The finding could help in the diagnosis and treatment of many human genetic diseases that lead to abnormal organ shapes, such as mitral valve prolapse, when the heart valve doesn’t form properly, and van Maldergem syndrome, which affects multiple organs.

“We believe that understanding how wing shape is controlled can also help us understand how the normal shape of many human organs is controlled,” says senior author Kenneth D. Irvine, a principal investigator at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology and a professor in the molecular biology and biochemistry department at Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

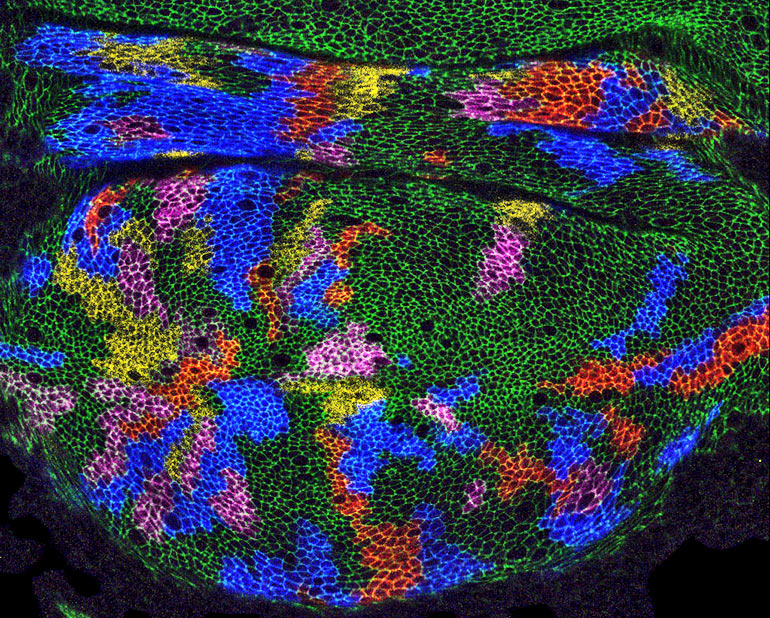

Researchers wanted to learn what controls organ shape. The normal function of organs in the human body requires a specific shape—and researchers wanted to know what controls that shape. They turned to the wing of the common Drosophila fruit fly to find out.

Scientists have long thought that how dividing cells orient or organize governs the shape of a growing fruit fly wing. But the new study shows that’s wrong.

Instead, tissue-wide stresses that dictate the overall arrangement of cells might serve as the blueprint for a wing without specifying the behavior of each cell.

The next step is to pinpoint mechanisms that control organ shape. Scientists are focusing on a set of genes required for normal organ shape in fruit flies and people, but don’t yet understand how the genes control shape, Irvine says.

“By identifying genes that influence organ shape, scientists could screen for alterations in those genes before the symptoms of a disease become evident,” he says. “If a disease is diagnosed before symptoms appear, people might be able to start a treatment plan to ameliorate the symptoms at an earlier stage.”

Graduate student Zhenru Zhou is the study’s lead author. Additional researchers from Rutgers and from the Institut de Biologie du Développement de Marseille in France contributed to the study.

Source: Rutgers University