The United States is in the grip of an opioid epidemic, affecting millions of Americans and claiming thousands of lives. Is suing drug companies, retailers, and doctors part of the answer?

Many people trace their opioid dependence back to their doctor’s office, the drugs prescribed for pain after an injury, surgery, or dental procedure. Were these painkillers over prescribed? Did drug manufacturers exaggerate opioids’ effectiveness while deliberately underplaying their danger? Did drug distributors and retailers take necessary steps to ensure that pills weren’t falling in to the wrong hands?

Here, Michelle Mello, an expert in health law, and Nora Freeman Engstrom, an expert in tort law and complex litigation, both professors at Stanford University, explain the scope of the opioid problem and discuss the latest cases and legal challenges.

Just how big of a problem is the opioid crisis in the United States? Can you describe the problem’s scope and seriousness?

Engstrom: The opioid problem is monstrous. Some 2.4 million Americans have an opioid use disorder, and the epidemic has already claimed 300,000 American lives, including 42,000 in 2016 alone.

Worse, if the problem isn’t addressed, death tolls will rise: opioids are on track to claim the lives of another half-million Americans within the next decade. That’s like wiping out the entire city of Atlanta.

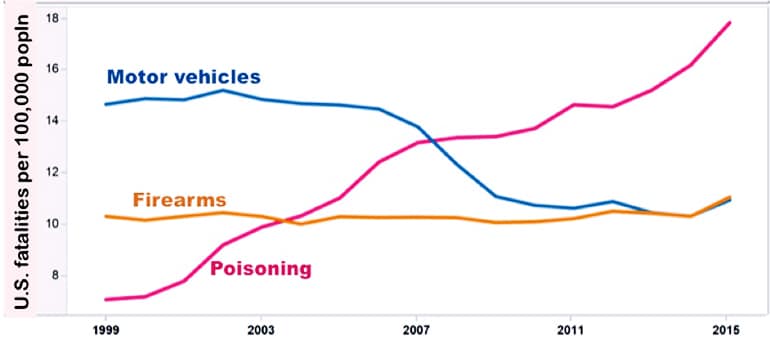

“In terms of what’s killing Americans, opioids dwarf car crashes and guns.”

The economic cost is also astronomical. The Council of Economic Advisors has estimated that, in 2015, “the economic cost of the opioid crisis was $504 billion, or 2.8 percent of GDP.”

Mello: If there’s one picture that brings home the shocking toll, it’s this one, showing trends in US deaths based on data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Nearly all of the “poisoning” deaths shown here are opioid related. In terms of what’s killing Americans, opioids dwarf car crashes and guns.

Opioid lawsuits are now making news. Some of the actions are criminal, pursued by the states and federal government. Others of those suits are being initiated by cities, counties, and even states. What do those latter suits allege and what damages are the public plaintiffs trying to recover?

Engstrom: In the past four years, roughly 400 cities, counties, and states have initiated lawsuits seeking recovery for their additional public spending traceable to the opioid epidemic.

The governmental entities claim they have been injured because defendants—typically, opioid manufacturers, distributors, and big retail pharmacies—have pumped opioids into the hands of their citizens and, in so doing, increased their spending for governmental services.

Everything from policing, education, foster care, the provision of health care, even the operation of coroner’s officers, have all been made more expensive because, as compared to a healthy citizenry, an opioid-addicted populace is far less productive and needs much more by way of government help.

Facing these spiraling costs, the governmental plaintiffs contend that the opioid defendants—who, they contend, caused and profited from this crisis—should foot the bill.

So, the typical defendants in these cases are opioid manufacturers, distributors, and big retail pharmacies. What is it that the plaintiffs are alleging these defendants did wrong?

Mello: There are some variations state to state, but for manufacturers, plaintiffs are typically claiming that they made false statements to prescribers and others that the drugs were safer and less addictive than alternatives, even when mounting evidence showed otherwise; that they failed to warn physicians and patients about the risks; and that the products were defectively designed—for example, because manufacturers didn’t make the pills tamper-resistant.

For distributors and retailers, the claims are that these defendants failed to monitor, detect, investigate, and report suspicious orders of prescription drugs, even though reasonably prudent suppliers would have done so and the federal Controlled Substances Act requires suppliers to maintain effective controls against diversion of controlled substances to illicit markets.

What about the physicians who prescribed excessive painkillers? Can they also be held responsible?

Engstrom: Private suits, initiated by patients against physicians, are, so far, relatively rare.

But that may change, as the path to holding physicians liable for harm to a patient arising from opioid use is relatively straightforward: if a physician violated the standard of care by prescribing painkillers that are inappropriate, prescribing the right painkiller but at an excessive dose, or failing to reasonably monitor a patient for signs of dependency, that constitutes medical malpractice.

A recent case out of Missouri is instructive. Brian Koon alleged that his physician prescribed “colossal” and “astronomical” doses of opioids for his back pain.

“The standard of care requires all healthcare providers to have a medication management system in place to make sure patients do not receive too many opioids.”

Koon became addicted to these painkillers and suffered damages. Koon sued the prescribing physician and won; the jury awarded roughly $1.7 million in compensatory and $15 million in punitive damages.

In upholding Koon’s award, the appeals court underscored physicians’ responsibilities going forward: “The standard of care requires all healthcare providers to have a medication management system in place to make sure patients do not receive too many opioids.”

According to the court, physicians have to weigh opioids’ risks, “prescribe the lowest effective dose for the shortest amount of time,” and evaluate patients for “signs of dependency.”

In short, the case makes clear that, when it comes to opioid abuse, doctors have duties too—and those physicians who disregard these obligations do so at their peril.

Mello: In addition to private suits, there are mechanisms for the government to go after physicians who overprescribe opioids.

For instance, “Pill Mill” laws in some states employ a variety of tactics to help identify and shut down storefront clinics that exist for the sole purpose of pumping out opioid prescriptions. State boards of medical licensing can take action against a prescriber’s license.

Is it important to go after physicians?

Mello: These measures can be helpful for addressing wildly inappropriate, very high-volume prescribing, but that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The harder problem is changing prescription practices among a much broader group of physicians who are trying to do the right thing, but not sure exactly what that is.

Physicians have come to rely too heavily on opioids, when other painkillers could suffice for a lot of patients. They were encouraged to do so not just by opioid manufacturers, but by a movement within the medical profession to address the widely recognized problem that pain was being undertreated.

The pressure on physicians to reduce opioid prescriptions now is such that the pendulum may be swinging too far in the other direction: prescribers may be withholding opioids from patients who truly need them.

So the trick is calibrating the legal pressure to get rid of harmful practices while making sure we don’t return to the days when chronic pain wasn’t taken seriously as a medical problem.

Returning to the litigation against companies, I understand that a federal judge in Cleveland has many of these cases, and he has convened talks between plaintiffs and drug companies to come up with a settlement. Who is this federal judge, and what is his position?

Engstrom: In federal courts, behemoth cases like this are consolidated for pretrial procedures into what we call multi-district litigation, or MDLs.

When an MDL is created, all the federal cases in the country that fall under the relevant umbrella (here, all opioid cases) are swept together and transferred en masse to a particular judge, who has been handpicked by a seven-member panel.

Then, that judge organizes the case, oversees discovery, tries a handful of test cases, and, very often, hammers out a global settlement.

In December 2017, the panel transferred all the federal opioid cases to Judge Dan A. Polster of Cleveland, Ohio. He’s a seasoned judge with plenty of MDL experience. He also sits in a state that is geographically located near many of the defendants and has a big opioid problem.

“What we’ve got to do is dramatically reduce the number of pills that are out there, and make sure that the pills that are out there are being used properly.”

Judge Polster has acted assertively to organize the litigation, and shown little tolerance for obfuscation and delay. He has set aggressive time-tables, ensured that the plaintiffs have the information they need to sort out “what the manufacturers, distributors, retailers and the DEA knew and when they knew it,” and has repeatedly indicated that he wants these cases resolved sensibly and expeditiously.

Further, any settlement, he says, must do more than just move “money around.” In his words: “What we’ve got to do is dramatically reduce the number of pills that are out there, and make sure that the pills that are out there are being used properly.”

Of course, achieving that goal won’t be easy. As is common in cases like this, Judge Polster has assigned three special masters to assist him. One, David Cohen, has pointed out that these suits are “one of the most, if not the most, complex pieces of litigation that the federal court system has ever seen.” Engineering the successful resolution of such a case will take an extraordinarily deft hand.

Have we seen similar cases before?

Mello: Litigation on a broad scale has become a common strategy for combating the health harms caused by dangerous products.

In particular, the opioid litigation bears many similarities to tobacco cases brought in the late 1990s.

There, as here, the plaintiffs argued that the sellers of an addictive, dangerous product made billions peddling that product while concealing and downplaying its risk.

In both cases, state attorneys general banded together to hold a major American industry accountable for a serious public health crisis under the glare of intense media scrutiny.

Engstrom: Yet, whether the tobacco litigation ought to serve as a blueprint or a cautionary tale depends on your point of view.

The tobacco litigation culminated in a blockbuster settlement of over $200 billion and included important concessions from tobacco companies that, among other things, curtailed marketing and led to the demise of such American mainstays as Joe Camel and the Marlboro Man.

Public health experts, however, look at the tobacco exemplar and see reason to worry.

States found a way of diverting the settlement money—originally intended to reduce tobacco use and to offset smoking-related health-care costs—to other channels.

Only 5-8% of the money was actually used for anti-tobacco programs. Thus, many experts believe that the tobacco settlement actually represents a squandered opportunity to tame tobacco use and caution against repeating that mistake with an opioid settlement.

Mello: The other thing to bear in mind is that, compared to the tobacco plaintiffs, the opioid plaintiffs face more legal barriers.

It’s not easy to convince a jury that an FDA-approved product is defective.

Further, in many states, if the drug’s packaging warns prescribers about a risk, manufacturers have no legal duty to also warn patients.

Finally, it can be hard to prevail on claims that a product manufacturer should be accountable for harms that arise from misuse of a product.

In the tobacco litigation, the smokers who fell ill were using the product precisely as intended; in contrast, many plaintiffs will have been prescribed excessive doses (meaning, the doctor rather than the manufacturer erred), taken more drug than was prescribed, or obtained opioids illegally.

Manufacturers can still be held liable for such misuse if it was reasonably foreseeable, but, for plaintiffs, drawing the causal arrow can be difficult.

Finally, as compared to the tobacco litigation, which was initiated by states and zeroed in on tobacco manufacturers, the opioid plaintiffs are themselves more heterogeneous and are seeking to pin liability on a larger cast of characters.

Engstrom: And in proving their claims, tobacco plaintiffs were greatly helped by the discovery of “The Cigarette Papers,” a massive, incriminating cache of industry documents leaked in 1994 that proved tobacco companies knew their products were addictive and manipulated nicotine content to foster addiction.

It remains to be seen whether the opioid plaintiffs will have similar luck, either within the formal legal process of discovery or through other channels.

Source: Stanford University