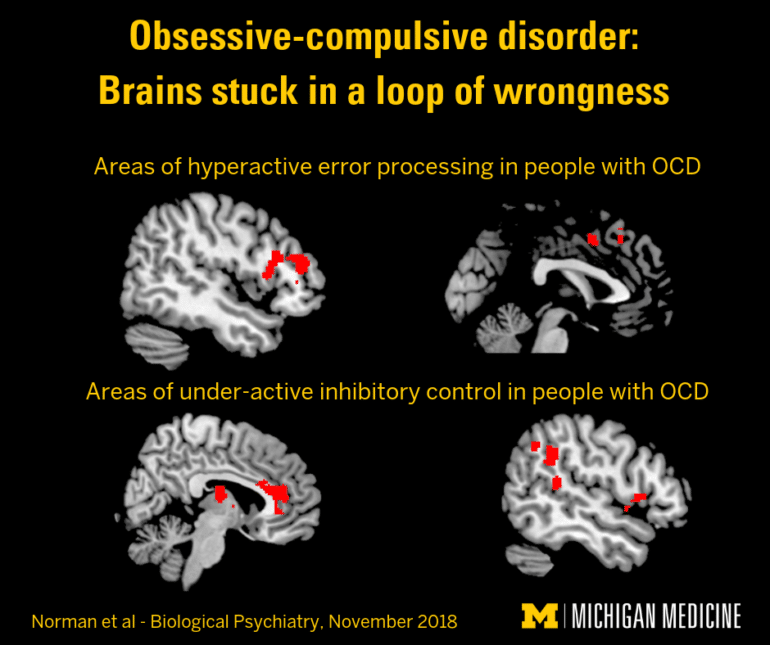

A study of hundreds of brain scans sheds light on abnormalities common to people with obsessive-compulsive disorder.

People with OCD may wash and re-wash their hands or check—and re-check, then check again—that the stove is off. But because the reasons for the behaviors are unclear, about half of patients don’t have effective treatment options.

Now, new research pinpoints the specific brain areas and processes linked to the repetitive behaviors common to patients with OCD. Put simply, patients get stuck in a loop of wrongness and can’t stop behaviors—even if they know they should.

Researchers gathered the largest-ever pool of task-based functional brain scans and other data from OCD studies around the world, and combined them for a new meta-analysis, which appears in the journal Biological Psychiatry.

Can’t stop

“These results show that, in OCD, the brain responds too much to errors, and too little to stop signals, abnormalities that researchers had suspected to play a crucial role in OCD, but that had not been conclusively shown due to small numbers of participants in the individual studies,” says lead author Luke Norman, a postdoctoral research fellow in the University of Michigan psychiatry department.

“It’s like their foot is on the brake telling them to stop, but the brake isn’t attached to the part of the wheel that can actually stop them.”

“By combining data from 10 studies, and nearly 500 patients and healthy volunteers, we could see how brain circuits long hypothesized to be crucial to OCD are indeed involved in the disorder,” he says.

The analysis “sets the stage for therapy targets in OCD, because it shows that error processing and inhibitory control are both important processes that are altered in people with the condition,” says Kate Fitzgerald, a faulty member in psychiatry.

“We know that patients often have insight into their behaviors, and can detect that they’re doing something that doesn’t need to be done. But these results show that the error signal probably isn’t reaching the brain network that needs to be engaged in order for them to stop doing it.”

Error monitor

Researchers focused on the cingulo-opercular network—a collection of brain areas linked by “highways” of nerve connections deep in the center of the brain. The area normally acts as a monitor for errors or the potential need to stop an action, and gets the decision-making areas at the front of the brain involved when it senses something is “off.”

Researchers collected the pooled brain scan data when people with and without OCD performed certain tasks while lying in functional MRI scanner. The analysis includes scans and data from 484 children and adults, both medicated and not.

It’s the first time a large-scale analysis has included data about brain scans performed when participants with OCD had to respond to errors during a brain scan, and when they had to stop themselves from taking an action.

A consistent pattern emerged from the combined data: Compared with healthy volunteers, people with OCD had far more activity in the specific brain areas involved in recognizing that they were making an error, but less activity in the areas that could help them stop.

More to the story

These differences aren’t the full story, the researchers say, and they can’t tell from the available data if the differences in activity are the cause, or the result, of having OCD.

But the findings suggest that OCD patients may have an “inefficient” linkage between the brain system that links their ability to recognize errors and the system that governs their ability to do something about those errors.

“It’s like their foot is on the brake telling them to stop, but the brake isn’t attached to the part of the wheel that can actually stop them,” Fitzgerald says.

“In cognitive behavioral therapy sessions for OCD, we work to help patients identify, confront, and resist their compulsions, to increase communication between the ‘brake’ and the wheels, until the wheels actually stop. But it only works in about half of patients. Through findings like these, we hope we can make CBT more effective, or guide new treatments.”

Not an anxiety disorder

Patients are often anxious about their behavior—but OCD is not an anxiety disorder, researchers say.

The researchers plan to test techniques aimed at taming that drive, and preventing anxiety, in a new clinical trial. In the meantime, the researchers hope that people who currently have OCD, and parents of children with signs of the condition, will take heart from the new findings.

“We know that OCD is a brain-based disorder, and we are gaining a better understanding of the potential brain mechanisms that underlie symptoms, and that cause patients to struggle to control their compulsive behaviors,” Norman says.

Adds Fitzgerald, “This is not some deep dark problem of behavior—OCD is a medical problem, and not anyone’s fault. With brain imaging we can study it just like heart specialists study EKGs of their patients—and we can use that information to improve care and the lives of people with OCD.”

The National Institutes of Health funded the work.

Source: University of Michigan