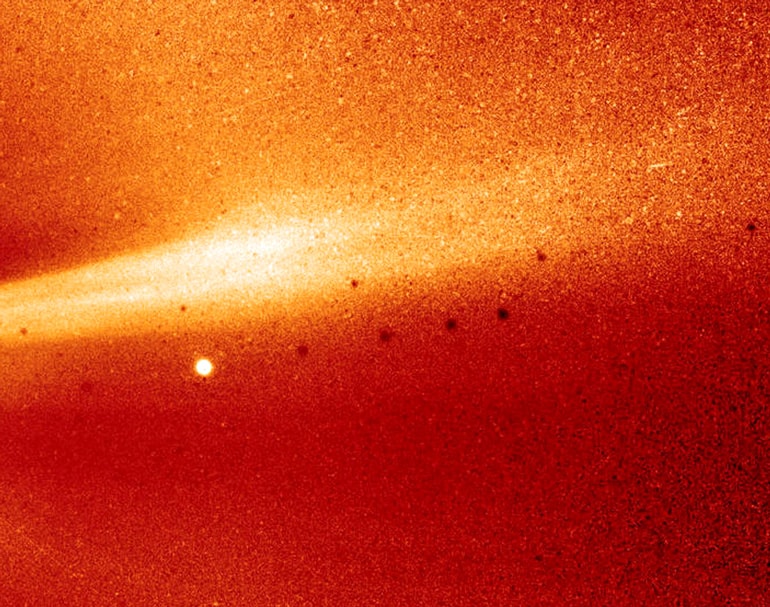

The closest-ever look inside the sun’s corona has unveiled an unexpectedly chaotic world, according to researchers from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission.

That world includes rogue plasma waves, flipping magnetic fields, and distant solar winds under the thrall of the sun’s rotation.

The findings, part of the first wave of results from the spacecraft that launched in August 2018, provide important insights into two fundamental questions the mission aimed to answer: Why does the sun’s corona get hotter as your move further away from the surface? And what accelerates the solar wind—an outward stream of protons, electrons, and other particles emanating from the corona?

“Even with just these first orbits, we’ve been shocked by how different the corona is when observed up close.”

Both questions have ramifications for how we predict, detect, and prepare for solar storms and coronal mass ejections that can have dramatic impacts on Earth’s power grid and on astronauts.

“Even with just these first orbits, we’ve been shocked by how different the corona is when observed up close,” says Justin Kasper, a professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the University of Michigan who serves as principal investigator for Parker’s Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons (SWEAP) instrument suite.

“These observations will fundamentally change our understanding of the sun and the solar wind and our ability to forecast space weather events.”

Four papers in Nature outline the findings from data collected during the spacecraft’s first two encounters with the sun. Kasper led one of the studies and is coauthor of two others (one, two).

The papers describe Parker’s unprecedented near-sun observations through two record-breaking close flybys, which exposed the spacecraft to intense heat and radiation. They reveal new insights into the processes that drive the solar wind—the constant outflow of hot, ionized gas that streams outward from the sun and fills up the solar system—and how the solar wind couples with the sun’s rotation.

Through these flybys, the mission also has examined the dust in the environment of the sun’s atmosphere, or corona, and spotted particle acceleration events so small that they are undetectable from Earth, which is nearly 93 million miles from the sun.

During its initial flybys, Parker studied the sun from a distance of about 15 million miles. That is already closer to the sun than Mercury, but the spacecraft will get even closer in the future, as it travels at more than 213,000 mph, faster than any previous spacecraft.

The Parker Probe sheds light on solar wind

Among the findings are new understandings of how the sun’s constant outflow of solar wind behaves. Seen near Earth, the solar wind plasma appears to be a relatively uniform flow—one that can interact with our planet’s natural magnetic field and cause space weather effects that interfere with technology. Instead of that flow, near the sun, Parker’s observations reveal a dynamic and highly structured system.

For the first time, scientists are able to study the solar wind from its source, the corona, similar to how one might observe the stream that serves as the source of a river. This provides a much different perspective as compared to studying the solar wind were its flow impacts Earth.

“By the time it gets to Earth, the solar wind is relatively smooth and well behaved, but close to the sun, it appears to be much more dynamic,” says coauthor Kristopher Klein, an assistant professor in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. “These local measurements of the solar wind represent the first steps into the region where the solar wind is still quite choppy and hasn’t been smoothed out yet.”

The spacecraft revealed that the sun’s rotation affects the solar wind much farther away than previously thought. Researchers knew that close in, the sun’s magnetic field pulls the wind in the same direction as the star’s rotation. Farther from the sun, at the distance the spacecraft measured in these first encounters, they had expected to see, at most, a weak signature of that rotation.

“To our great surprise, as we neared the sun, we’ve already detected large rotational flows—10 to 20 times greater than what standard models of the sun predict,” Kasper says. “So we are missing something fundamental about the sun, and how the solar wind escapes.

“This has huge implications. Space weather forecasting will need to account for these flows if we are going to be able to predict whether a coronal mass ejection will strike Earth, or astronauts heading to the moon or Mars,” Kasper says.

The sun’s magnetic field

Parker Solar Probe’s findings regarding the sun’s magnetic field—which is believed to play a role in the coronal heating mystery—were equally surprising. From Earth’s vantage point, researchers detected magnetic oscillations called “Alfvén waves” in the solar wind long ago. Some researchers thought they may be remnants of whatever mechanism caused the heating phenomenon.

Parker researchers were on the lookout for indications that might be the case, but found something unexpected.

“When you get closer to the sun, you start seeing these ‘rogue’ Alfvén waves that have four times the energy than the regular waves around them,” Kasper says. “They feature 300,000 mph velocity spikes that are so strong, they actually flip the direction of the magnetic field.”

Those polarity-reversing velocity spikes offer another potential candidate for what may cause the corona to get hotter moving away from the sun.

“All of this new information from Parker Solar Probe will cause a fundamental rethinking of how the magnetic field of the sun behaves and is coupled to the acceleration of the solar wind,” says Lennard Fisk, professor of climate and space sciences and engineering.

“This is the closest we have ever observed a coronal-mass-ejection related energetic particle event,” and member of the ISʘIS instrument team. “Parker was about 50 solar radii from the sun at the time.

“We are observing the sun’s outer atmosphere where we never have before,” says Joe Giacalone, a professor at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “This is exciting. Much of what we have seen was not expected. These initial observations still require some interpretation, which will help us better understand how the sun—and, by extension, other stars—work.”