The most frequent and most public opioid abusers may be the best people to train how to give anti-overdose drugs to fellow users in trouble, a new study suggests.

Public health departments and community organizations have started to train opioid users to administer naloxone to save other users who overdose. The question is which users should get training priority?

“A user can’t administer naloxone to himself when he’s overdosing, so, from a public health standpoint, we need to figure out which users are most likely to witness other users’ overdoses and, thus, be in position to revive them,” says Carl A. Latkin, professor of health, behavior and society at Johns Hopkins University.

Scientists interviewed 450 Baltimore drug users, the vast majority with histories of opioid abuse. The users who witnessed more drug overdoses by others tended to be those who engaged in riskier drug use and used drugs in more places, the scientists found.

“Our results indicate that the likeliest overdose witnesses are the heavier users who use in a wider range of settings,” Latkin says.

The study, published in Substance Abuse, comes as the opioid crisis continues to worsen across the United States. Emergency room visits for opioid overdoses surged by a third in 2016-2017, and daily opioid-overdose deaths now average 115, government statistics show.

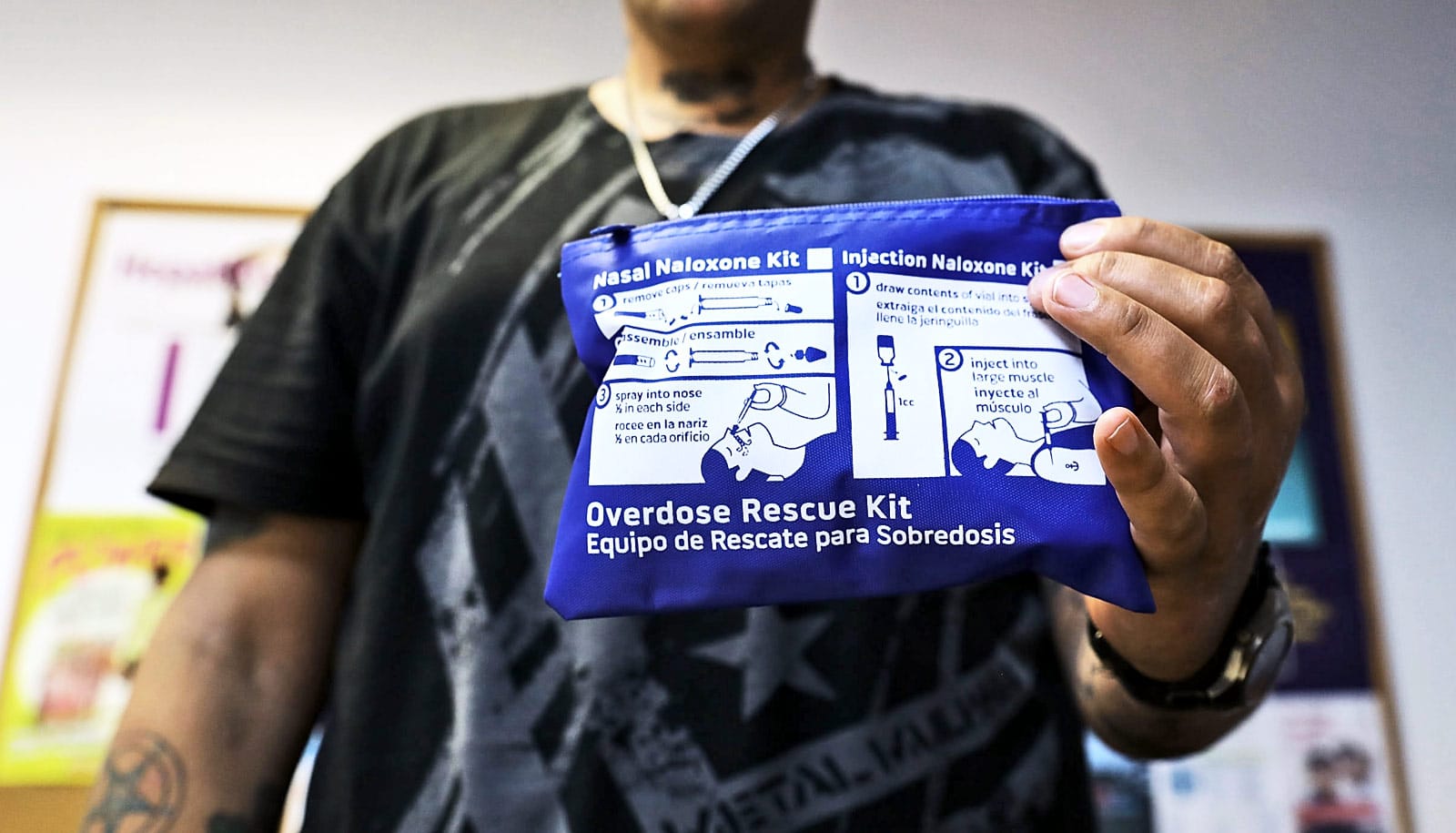

Opioid drug overdoses can easily be fatal because the drugs suppress brain cell activity that controls breathing. Naloxone, administered by injection or nasal spray, blocks opioids’ effects on brain cells, so it can quickly restore normal breathing and consciousness in an overdose victim.

However, there is often only a brief window for its effective use—particularly when the overdose involves one of the more potent opioids, such as fentanyl.

“Since fentanyl is more potent and faster-acting than heroin, you really need to ensure that naloxone is immediately available in the case of an overdose,” Latkin says.

Many states now allow pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription and sanction naloxone training and distribution programs by health organizations. But how to direct limited supplies of naloxone most effectively has been an unanswered question.

The study stems from a larger HIV risk-reduction project in which researchers interviewed hundreds of impoverished Baltimore opioid users about their drug use.

Latkin and colleagues from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health analyzed interview data to find factors that would allow them to identify users who were most likely to witness overdoses and who might, therefore, be good candidates for naloxone training.

Emergency ‘NaloxBox’ could let public prevent overdoses

The analysis covered 450 participants who had provided relevant information on their drug-use behaviors. Roughly 75 percent of these users reported that they had witnessed an overdose. About 12 percent had witnessed more than five.

Not surprisingly, those who had witnessed more overdoses tended to be those whose behaviors indicated a deeper involvement in drug abuse. The behaviors most strongly associated with witnessing overdoses included injecting with heroin and/or “speedball” (cocaine plus heroin), snorting heroin, having an overdose history, using city needle-exchange programs, and using drugs in a greater variety of places—such as public restrooms, “shooting galleries” and abandoned buildings.

$1 test strips find fentanyl in street drugs

“These results give us some clues about the individuals we should be training in the use of naloxone,” Latkin says. “Drug users have consistently demonstrated their abilities to help others prevent HIV and treat overdose victims.”

The National Institute on Drug Abuse funded the work.

Source: Johns Hopkins University