Patients are less likely to fill prescriptions for naloxone when they face increases in out-of-pocket costs, according to new research.

The study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, utilized data from a national pharmacy transactions database from November 2020 to March 2021. The researchers found that about 1 in 3 naloxone prescriptions for privately insured and Medicare patients were not filled.

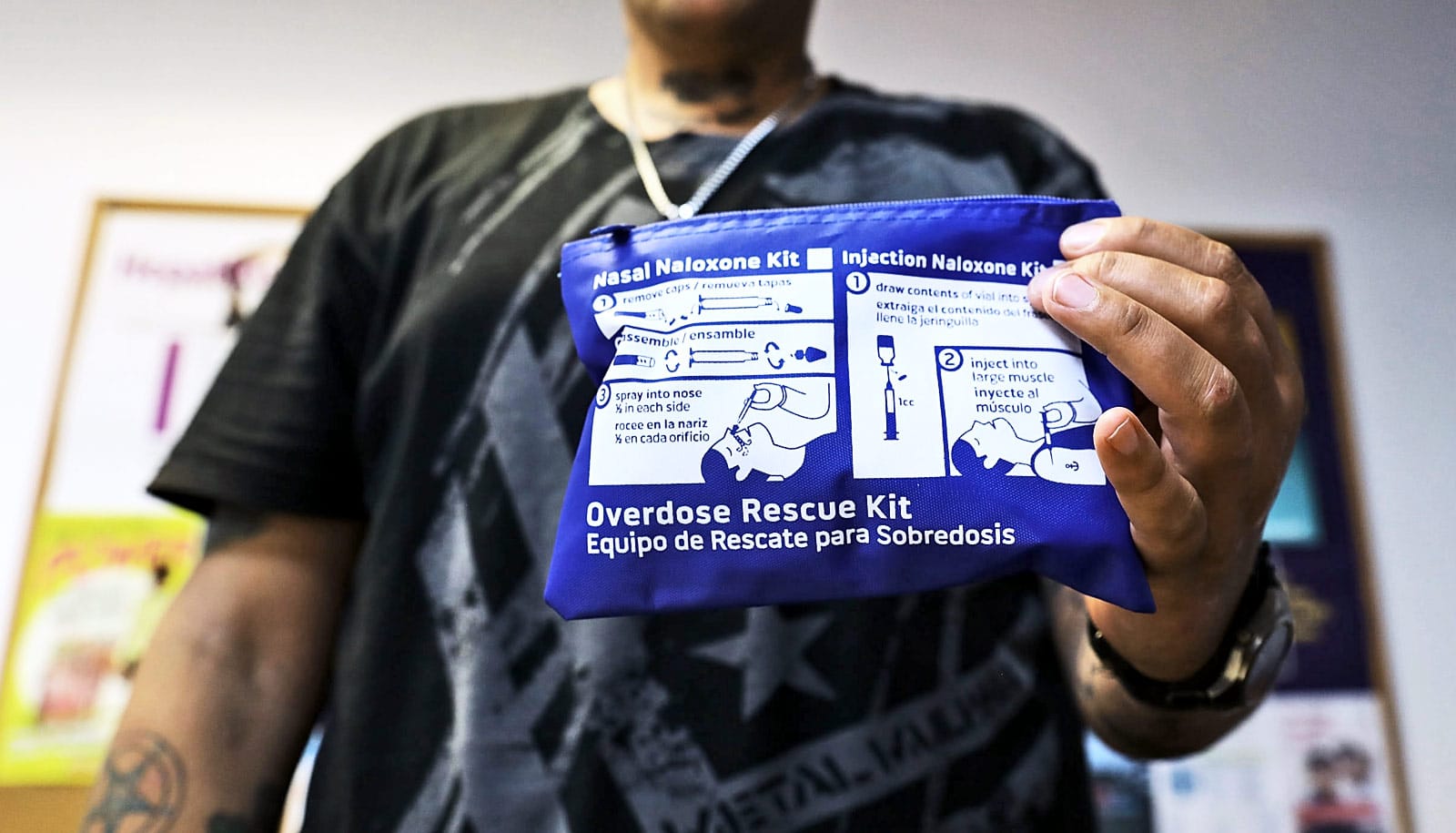

Naloxone, an opioid antagonist that can reverse overdose, is a critical tool in preventing overdose deaths. Nationally, opioid overdoses account for more than 78,000 deaths annually, according to provisional data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The rate of nonfilled prescriptions across the country jumped abruptly on January 1, 2021—the date on which deductibles reset in many private and Medicare plans—as did the amount patients had to pay to fill prescriptions. The researchers estimate that a $10 increase in out-of-pocket cost would decrease the rate of filling prescriptions by about 2 to 3 percentage points.

“Minimizing barriers to accessing naloxone is a crucial step toward slowing the US opioid epidemic. Our study suggests that minimizing the out-of-pocket cost of naloxone prescriptions could help achieve this goal,” says lead author Kao-Ping Chua, assistant professor at the University of Michigan Medical School and School of Public Health.

Chua and colleagues note that barriers to naloxone dispensing other than cost also play a key role in addressing this issue, such as stigma about the medication. For example, the study also found that 7%-8.5% of naloxone prescriptions were not filled even when they were free to patients.

A Michigan-specific strategy seeking to mitigate barriers to naloxone access and use was announced late last year, when the state issued an updated statewide standing order.

As written in the order, community-based organizations are now able to host or provide naloxone distribution sites without the previously required oversight of a pharmacy. These “naloxone vending machines” provide the lifesaving medication for free and increase access for those in need without a prescription.

Chua is co-director of Research and Data Domain at the University of Michigan Opioid Research Institute (ORI) and faculty member at the Susan B. Meister Child Health Evaluation and Research Center (CHEAR) and Institute for Healthcare Policy and Innovation (IHPI).

Additional coauthors are from the University of Michigan and Boston University.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Gorman Scholar Award from the University of Michigan Medical School supported the work. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Kate Barnes for University of Michigan