The mathematical puzzle called the “moving sofa problem” poses a deceptively simple question: What’s the largest sofa that can pivot around an L-shaped hallway corner?

A mover would tell you to just stand the sofa on end. But imagine the sofa is impossible to lift, squish, or tilt. Although it still seems easy to solve, the moving sofa problem has stymied math sleuths for more than 50 years. That’s because the challenge for mathematicians is both finding the largest sofa and proving it to be the largest. Without a proof, it’s always possible someone will come along with a better solution.

“It’s a surprisingly tough problem,” says Dan Romik, professor and chair in the mathematics department at the University of California, Davis. “It’s so simple you can explain it to a child in five minutes, but no one has found a proof yet.

The largest area that will fit around a corner is called the “sofa constant” (yes, really). It is measured in units where one unit corresponds to the width of the hallway.

Inspired by his passion for 3D printing, Romik recently tackled a twist on the sofa problem called the ambidextrous moving sofa. In this scenario, the sofa must maneuver around both left and right 90-degree turns. His paper is available on arXiv and in the journal Experimental Mathematics.

Romik, who specializes in combinatorics, enjoys pondering tough questions about shapes and structures. But it was a hobby that sparked Romik’s interest in the moving sofa problem—he wanted to 3D print a sofa and hallway. “I’m excited by how 3D technology can be used in math,” says Romik, who has a 3D printer at home. “Having something you can move around with your hands can really help your intuition.”

There’s finally a proof for this Graph Theory puzzle

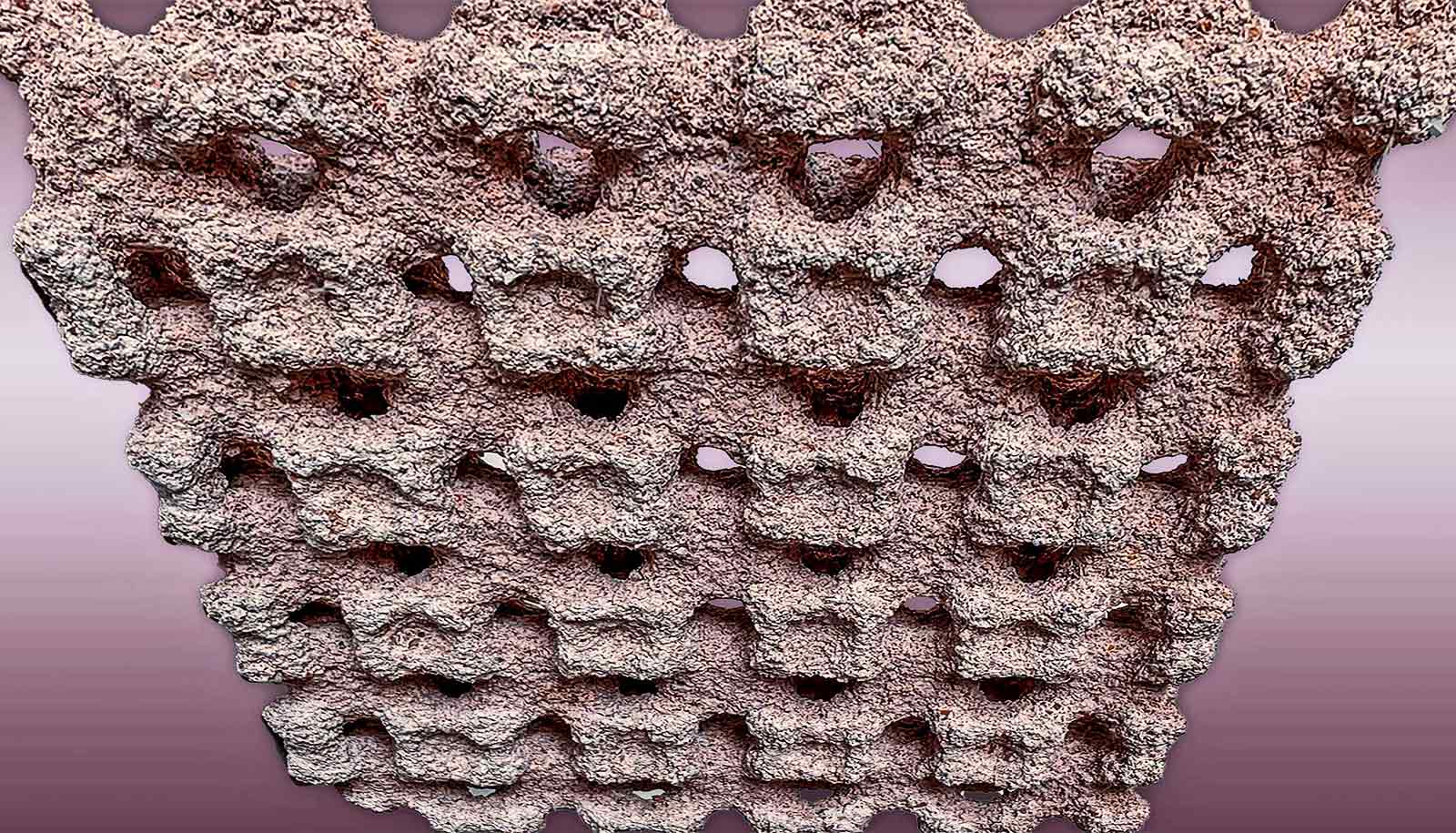

The Gerver sofa—which resembles an old telephone handset—is the biggest sofa found to date for a one-turn hallway. As Romik tinkered with translating Gerver’s equations into something a 3D printer can understand, he became engrossed in the mathematics underlying Gerver’s solution.

Romik ended up devoting several months to developing new equations and writing computer code that refined and extended Gerver’s ideas. “All this time I did not think I was doing research. I was just playing around,” he says. “Then, in January 2016, I had to put this aside for a few months. When I went back to the program in April, I had a lightbulb flash. Maybe the methods I used for the Gerver sofa could be used for something else.”

Romik decided to tackle the problem of a hallway with two turns. When required to fit a sofa through the hallway corners, Romik’s software spit out a shape resembling a dumbbell, with symmetrical curves joined by a narrow center. “I remember sitting in a café when I saw this new shape for the first time,” Romik says. “It was such a beautiful moment.”

Like the Gerver sofa, Romik’s ambidextrous sofa is still only a best guess. But Romik’s findings show the question can still lead to new mathematical insights. “Although the moving sofa problem may appear abstract, the solution involves new mathematical techniques that can pave the way to more complex ideas,” Romik says. “There’s still lots to discover in math.”

Source: Becky Oskin for UC Davis