A new medicated skin patch turns energy-storing white fat into energy-burning brown fat and raises the body’s overall metabolism, report researchers.

The patch, so far only tested in mice, may one day burn off pockets of unwanted fat and treat metabolic disorders like obesity and diabetes in people.

Humans have two types of fat. White fat stores excess energy in large triglyceride droplets. Brown fat has smaller droplets and a high number of mitochondria that burn fat to produce heat. Newborns have a relative abundance of brown fat, which protects against exposure to cold temperatures. By adulthood, most of the brown fat is gone.

For years, researchers have searched for therapies to change an adult’s white fat into brown fat—a process called browning that can happen naturally when the body is exposed to cold temperatures—as a treatment for obesity and diabetes.

“There are several clinically available drugs that promote browning, but all must be given as pills or injections,” says Li Qiang, assistant professor of pathology and cell biology at Columbia University and co-lead author of the study in ACS Nano. “This exposes the whole body to the drugs, which can lead to side effects such as stomach upset, weight gain, and bone fractures.

The new skin patch appears to avoid these complications by delivering the drugs directly to fat tissue.

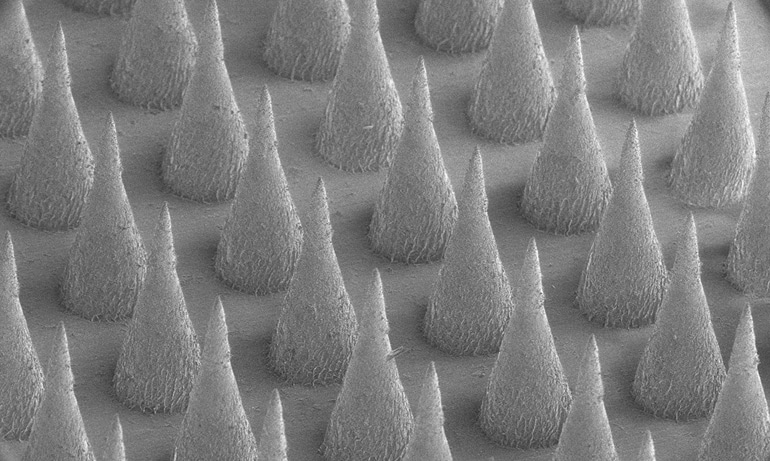

During experiments, the drugs were first encased in nanoparticles, each roughly 250 nanometers in diameter—too small to be seen by the naked eye. (In comparison, a human hair is about 100,000 nm wide.)

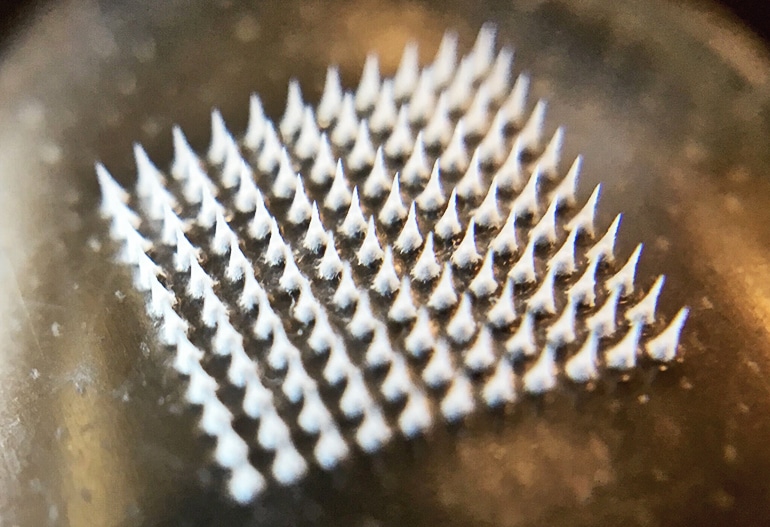

The nanoparticles are then loaded into a centimeter-square skin patch containing dozens of tiny needles. When applied to skin, the needles painlessly pierce the skin and gradually release the drug from nanoparticles into underlying tissue.

“We designed the nanoparticles to effectively hold the drug and then gradually collapse, releasing it into nearby tissue in a sustained way instead of spreading the drug throughout the body quickly,” says patch designer and study co-leader Zhen Gu, associate professor in the joint University of North Carolina-North Carolina State biomedical engineering department.

Researchers tested the new treatment approach in obese mice by loading the nanoparticles with one of two compounds known to promote browning: rosiglitazone (Avandia) or beta-adrenergic receptor agonist, which works well in mice but not in humans.

The researchers used two patches for each mouse. One patch was loaded with drug-containing nanoparticles, and the other patch held no drugs. They placed the patches on opposite sides of the lower abdomen. New patches were applied every three days for a total of four weeks. Control mice received two empty patches.

“Many people will no doubt be excited to learn that we may be able to offer a noninvasive alternative to liposuction for reducing love handles.”

Mice treated with either of the two drugs had a 20 percent reduction in fat on the treated side compared to the untreated side. They also had significantly lower fasting blood glucose levels than untreated mice.

Tests in normal, lean mice revealed that treatment with either of the two drugs increased the animals’ oxygen consumption—a measure of overall metabolic activity—by about 20 percent compared to untreated controls.

Genetic analyses revealed that the treated side contained more genes associated with brown fat than on the untreated side, suggesting that the observed metabolic changes and fat reduction were due to an increase in browning in the treated mice.

Blocking protein may turn bad fat brown

“Many people will no doubt be excited to learn that we may be able to offer a noninvasive alternative to liposuction for reducing love handles,” Qiang says. “What’s much more important is that our patch may provide a safe and effective means of treating obesity and related metabolic disorders such as diabetes.”

The researchers are currently studying which drugs, or combination of drugs, work best to promote localized browning and increase overall metabolism. The patch has not been approved for testing in humans.

The National Institutes of Health and the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute funded this work.

Source: UNC-Chapel Hill